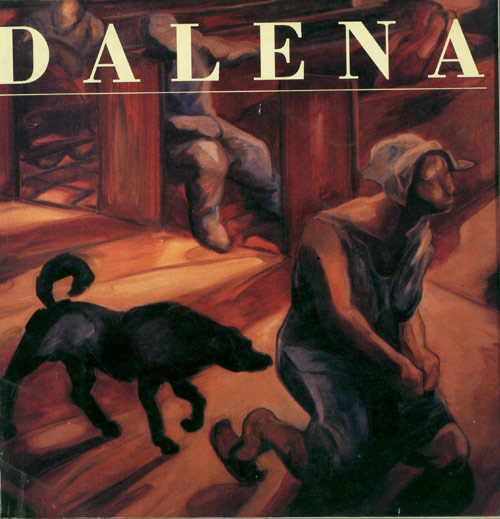

The Quiapo and Pakil of Danny Dalena

by: Alice G. Guillermo, Erwin Castillo and Quijano de Manila

December 2015--Danny Dalena appeared with a bang in the early seventies. He first made his mark with a brilliant and caustic political cartoons and illustrations for the Free Press Philippine Leader which gave new life to editorial cartooning and brought out the exciting potentials of the graphic arts in our country. This was followed by his Jai-Alai Series which placed him high on the roster of AAP winners and won for him the Mobil Art Grand Award for painting 1980.

This present CCP show is survey rather than a retrospective of the artist’s works and Dalena himself emphasizes its ongoing quality of art still in the process of being produced. Included are his political cartoons of 1970 to 1972 and the more recent ones for Midweek magazine in 1985, the toilet and graffiti drawings of 1972, paintings from the Jai-Alai Series from1974 to 1979, the Alibangbang Series in 1980, the Quiapo paintings in 1979 and the present Pakil Series from 1984 to the present.

Dalena honed his art in hundreds of characters studies, figure drawings of down-and-out betting hall and beerhouse types. In these highly concentrated images is revealed an endless obsession with morality in the telltale wrinkle of skin, the ugly folds of fat, the sweet and grime ill-concealed beneath the worn clothes. The superb fluency of drawing captures an entire vocabulary of intimate and physical body language, so highly nuanced and yet so transitory, in lines that saucily arch a curve of hip or tellingly bring out the lassitude nonchalance of an arm slung over the back of chair.

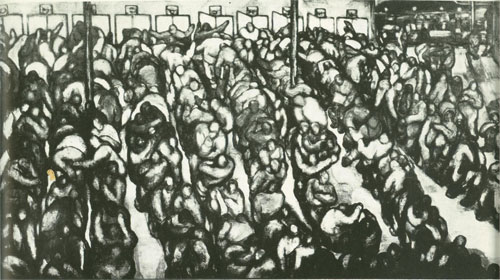

The Jai-Alai series in oil on canvas was a culmination of the figure drawings now rendered in paintings of epic perspective on the subject of swarming masses in search of luck or miraculous relief. In these paintings done in the bleak martial law years, the betting halls become a metaphor for the human condition, particularly in Philippines society in crisis. The Game, like an arbitrary throw of dice with its winning combination of numbers and mesmerizes and provokes in the crowds of the oppressed and unemployed a temporary heightened existence compounded by hope and despair, by monstrous jubilation and drunken despondency.

The Alibangbang series followed in the same vein. But this time its setting was a Cubao beerhouse, all smoke, sweat, and stale beer, with gyrating a-go-go dancers, heightening the pulse of the habitués. Meanwhile, he continued to fill his sketchpads with drawings of down-and-out and his nights of the prowling of city and its beer joints led to the series of toilet drawings, starkly and unsparingly realistic from aggressive graffiti down to the last trickle of human ooze, all of which make straight for the guts like a swig of strong whisky. In Danny’s bar, there are no lady’s drinks, only hard liver curding stuff.

He began work on Quiapo series in 1979 but he has not yet exhausted the material. In 1984, he set off for Pakil, his hometown where he has since discovered a wealth of folk life and culture of which he easily feels himself a part and at the same time a tireless observer.

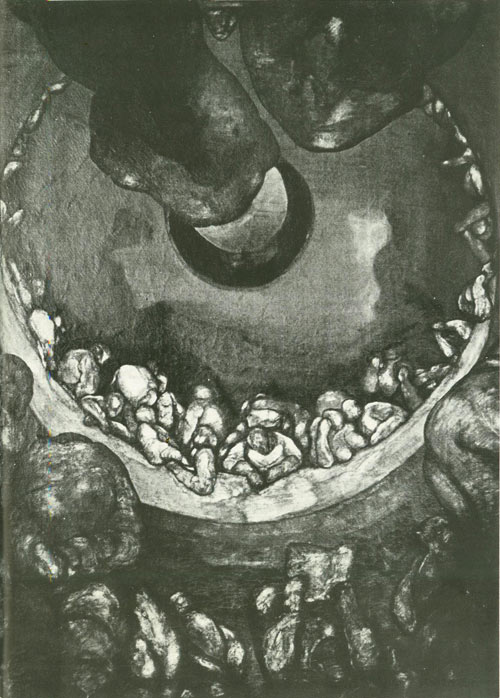

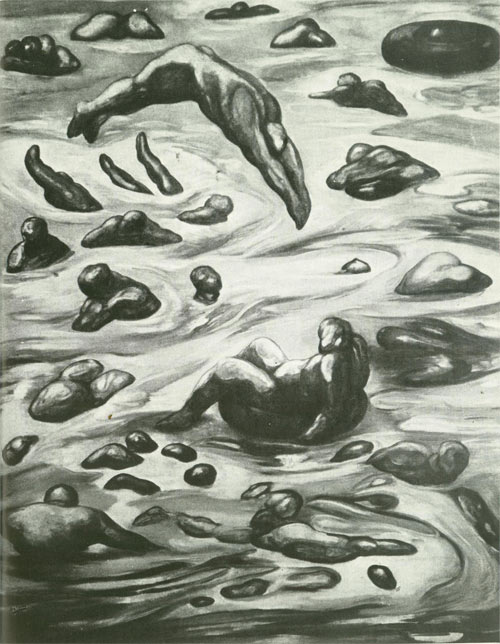

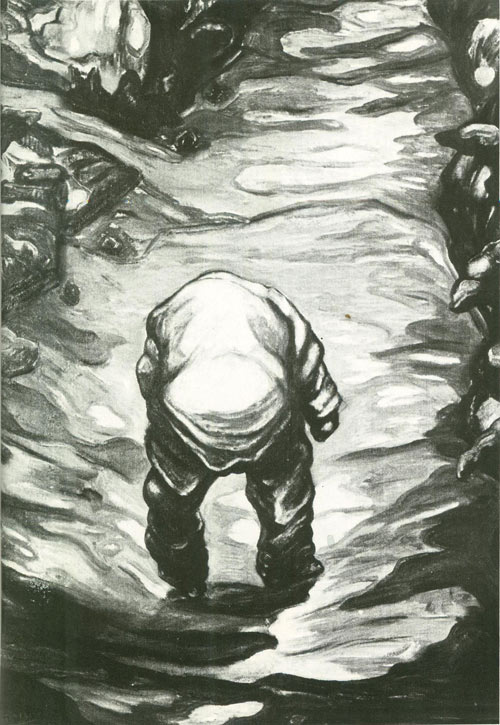

Thus, from the urban spleen of Jai-Alai and Alibangbang, Dalena discovers fresh wellsprings of artistic energy in the folk life of Pakil, his hometown. A quiet and conservative place, proud of its beautiful church, the town spring to life during the Turumba fiesta which attracts devotees all over the country. This inevitably brings in the religious theme into artistic work. Unlikely, one might think, after the steamy and carnal climate of Alibangbang and the squalid scenes of the city toilets, all done in a hard-nosed secular spirit. What relates the Pakil series to these earlier works however is the same sense of milling crowds, of commingling bodies in a sea of movement and the same mindless and mesmerized fervor.

In Dalena’s crowd paintings, the people are not mere numerical aggrupation of figure. For one, they are highly cohesive, seemingly possessed by a common force in the contagion of pressing bodies. More importantly they are marked by a strong and undeniable physicality, as in the rest of his paintings. As in our familiar experience with crowds in jeepneys, buses, churches and public places, the artist is keenly aware that in public situation our masses do not strive to maintain, consciously or unconsciously, a minimum spatial between bodies, but are most comfortable and assured rubbing elbows and knees, feeling their warm and moving bodies pressing together. Thus his paintings convey an immensely sensuous, indeed sensual, uninhibited fluidity that lends itself very well to great commingling masses. Likewise, their sensuousness exudes a complex aroma of human effusions simmering in the long summer’s heat.

Painting for the artist is essentially a sensuous and sensual experience. In his pursuit of the common denominator of senses, he has explored the realm of primarily bodily function in paintings and drawing of men pissing in sordid public toilets, a series which sharpened his sensitivity to the human form in varying attitudes of physical tension and release. To further this preoccupation, dogs play a role with their directly instinctual behavior. In works such as Asong Gala and Asong Simbahan. Dogs wantonly lolling on the aisle of sniffing at worshiper bear strong sexual connotations. Even more they continue the vein of social satire in Dalena as he irreverently pokes at small town conservatism and simply folk piety. The dogs as demystifying symbols expose the lust of the flesh that the shadowy observe or the dark twin of religious ritual and gesture. In the procession of the Virgin of Turumba who is also Our Lady of Sorrows, the devotees sing and gyrate in the streets not so much to call her attention but to make her smile and be indeed the lady of milling throng.

The fiesta becomes an occasion for making wry commentary on folk culture. In painting of Quiapo procession, rain pours down on the devotees with their umbrellas, but for the Nazarene a large plastic sheet covering his entire figure saves the occasion as it is carried above the crowd, recalling ones childhood dolls in the glass aparador or the sala sets still in their plastic covers. The Komedya sa Pakil is a colorful rendering of the performances, done in an unalloed spirit of spontaneity and capturing the naïve charm of the swashbuckling swordplay in the improbable costumes.

And then there are the portraits drawings and paintings, which are again not static, but situational and indicative of mood. Most of these, from the Jai-Alai and Alibangbang Series, are cuttingly realistic. A rare piece is Luling Olympia, a Pakil matriarch and the artist’s mother, a tongue-in-cheek spoof of Manet’s Olympia, as she lounges wide awake on the settee with the children taking their nap on the floor and others sitting on the window still facing the church and the Sierra Madre Mountains to breathe the still unpolluted air and watch the world go by at a snail’s pace in Pakil.

Yet Dalena’s satire, while caustic and cutting, is not all dark and heavy. It always bears a note of humor, like a sly left handed compliment. And this is where he is part of what he satirizes; this where he is soul brother to his shadow night denizens and to the down-and-out habitués of betting halls and beer joints. In Pakil, Danny is always looking out of the window of his ancestral house to the town where he picks up from where he left in his childhood. Like Many Filipinos, he is both hardened city boy and rural naïve, and his art is all the more enriched by it.

NOTES ON A FRIEND

by: Erwin Castillo

And as customary among us, the ceremony lasting for years, Dannyboy Dalena gradually took possession of the house, the edifice of osmosis taking on the quirks of the heir, grow metamorphosing into gorgeous jungle: the trees, the books in their cases, the antiquities all in daily use, leather-bound albums crammed with fading photographs of severed head gathering aphids and flies in the dirt streets of farrago Shanghai and the dead musicians fondling their instruments and their whores, so many strands of rope, vine and silver chain dangling there mythical dog howls in the rain( or is it Recah belching?) the ghost-dog Abu guardian of the temple.

There is a clearing in the wilderness dominated by an altar incandescent in jade and bloodstone. The joyful Rock-O-La makes insistent delirious confabulation. The crocodiles in the banks of the lake open their monstrous mouths. The tropical birds scream. Now the drunken folk and women rise hesitantly to dance. Then, to frenzy. They dance – they pray – for coming of the children safely. They dance for grace, for love, for their wretchedness to be considered and justified.

It is Turumba –time at Alibangbang.

Michelangelo believed that sculptured form was latent. In the stone and the work of art was to scrape away the non-essential to reveal purity and power hidden there. So it may be with Dannyboy, working away with canvass and paper to see the lottery number printed there. Dannyboy paints – – as drunken folk and the woman dance and pray – – to apprehend the secret series of number, the catalytically sequence that – when spoken aloud, when painted shall explain away our pain and sufferings, rouse our dead, break the dam and allow the river of justice to flow down. The game as Dannyboy knows, is loaded in favor of injustice and anarchy: one hundred trillion of combination to bet on in one short lifetime.

Meanwhile the Sierra Madre moves like a woman in deep love.

Dannyboy grins maniacally. We are sitting around the food table set up in an Intramuros ruin one night of the full moon. Dannyboy is drinking. The moonlight glints into the shanty roofs. There is a large commotion. They are running towards us, first the children, then the women. The men are panting.

Amok! Amok! They shout.

The murderer approaches out of the darkness. A long thin man garlanded with sampaguita blossoms, an in each hand a knife. We rise to flee, except for Dannyboy who shuffles forward to meet the man, and we can stop him they are abreast, the painter and the anarchist a brace of desperadoes.

Who knows what it is that was said there in the moonlight when they met, the priest and the Hun? But before we regain our senses the murderer is kneeling down, weeping being baptized in the brine of his confusion and his tears. Civilization is, for a while safe. Perhaps Dannyboy gave him a tip on the horse races.

Later it rains and suddenly Dannyboy command the taxi driver to stop. He flings the car door open and runs out of the garbage heap. He bears his price back to the cab, having retrieved another clue to the secret. It Is a funeral wreathe, days old, but it reveals a name and a series of numbers. Dannyboy is happy, wet deciphering the code in the light of his burning eyes and the neon’s.

Aha! He shouts, thinking – no, praying that – he has found the combination to the vault of the hard heart of God.

On to the Jai-Alai!

EXCERPTED FROM THE 1990 MOBIL ART AWARD BOOK

by: Alice Guillermo

Vision and range distinguish the art of Danilo Dalena, painter, sculptor, and editorial cartoonist. It is an art that registers the pulse of Philippine society with sensitivity born out of constant observation and participation in the living mainstream.

Dalena’s jai-Alai series in 1977 through 1978 creating of the image of the betting hall a metaphor for the human condition. There, thousands of people flock as to a shrine of last resort, the glistening bodies pushing, elbowing their way, or simply learning on one another and waiting for the stroke of luck. They are all here: the compulsive bettors, the hangers-on, the laid-off casuals, the born losers, the perpetual imbibers, the nocturnal denizens, and gaudy females. Dalena’s painting plumb the depth of human squalor and deprivation relieved here and there by the ray of light, a glimpse of salvation.

One of the most remarkable canvases of the series is entitled Last Call to Place your Bets. A large painting, 28 ½ x 59 1/2, the swarming crowd is seen from the great height, with the objectivity of an omniscient view. The hall becomes a limbo of writhing and struggling bodies, hundreds, yes, thousands, their survival hanging by a slender thread. Event 13 has the same view from a height, but here the multitude seems temporarily appeased, waiting in rows of seat that resemble long lines of pews separated by a nave in the half-light of the church-like edifice. One, in fact, with the title Simbahan (Church), reverses the viewpoint, this time being an upward look to the circular skylight of the building, like giant oculus, though neither heroic nor Olympian now as in the Pantheon, but crowded all around with ragtag multitude of people watching the events in the arena below. The view of these crowds, these masses of people straining for relief in a precarious existence, their single minded pursuit of luck, become a staggering and unforgettable image of Dalena’s work.

Aside from these large epic paintings, Dalena has also done numerous character studies which form part of the same series. All are captured in canvas: the altitude of tension and lassitude, the expressions of vacuity, greed, surprise, despair. Early bird shows an eager devotee arriving at the game hall with the shock of morning light behind him rendering his blue baggy pants and shirt transparent while he intently writes his day’s number into booklet. Details such as chain of his pocket watch hanging from his belt are individualizing marks (Left Out) shows a waiting whore in skimpy clothing, revealing the unflattering lumps and folds of ageing flesh, while Talo (Defeated) is an awkward shapeless hulk moping privately over his loses. It is a world devoid of glamour as the artist probes life in the raw, objectively and without idealization, in style characterized by slice-of-life naturalism. It is also thoroughly urban, but seamy urban.

Dalena’s body of work in the last decade shows a versatile talent capable of a wide range of expression from biting satire to playful pop, as well as competent in handling a combining various media, even the non-traditional. The artist had earlier won recognition for his editorial cartoons done by the Asia-Philippines Leader before the declaration of martial law in the country in 1972. These cartoons, in their sharpness of insight, wit , and richness of invention and imagery deserve their own separate recognition, remaining as they are unexcelled in the history of Philippine cartooning, and indeed worthy of a place in the international scene.

YOU CAN GO HOME AGAIN

by: Quijano de Manila

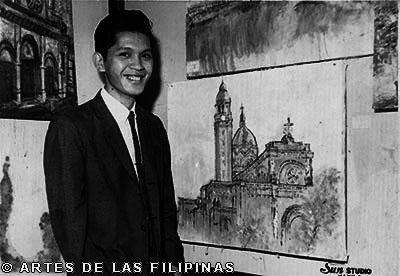

Funky, meaning “campily offbeat” was the word for his art when Dalino Dalena started out in the late 1960’s in his early 20’s, fresh out of Santo Tomas University and with a good job in the Free Press Magazine’s art department.

And Funky still in Danny Dalena, pushing 50 and staying bohemian, though his art has traced an odd parabola from the campy and offbeat to the reverent and traditional. What began as street smart Manila boy is now devout Pakil hometowner, obsessed with custom and ceremony. It turns out that all the time he was going into phallic symbols and a go-go bars and café latrines and the Jai-Alai he had been really making his way home to Pakil, his ancestral town, where his art now finds its supremest expression.

This bizarre progression may be pondered in his big show this year which is summation of the work he has done since 1970’s. Work done before then he dismisses as apprentice effort, like the oil paintings of his first one-man show, in 1969, at Joy Dayrit’s Print Gallery.

“That was a mixed batch of some 25 canvases, mostly in primary colors, though sometimes with secondary accents. One was the Virgin of Antipolo: several were of a go-go dancer. Hindi pa masyadong lutong luto. No. portraits, no landscapes. O got good commentaries, especially from artist, Fernando Zobel. Lee Aguinaldo liked the show very much and persuaded me to personally donate one painting to the Ateneo Art Gallery. It’s still there. I’m rather surprised to hear it referred to as from my abstract period. It’s supposed to be a dancer and the colors are dark and luminous orange.”

Later in 1969 Danny had another one-man show, at the Norther Motors showroom on the UN Avenue, this time of plastic sculptures:” Medyo Luto na.” This was the show that earned him the tag of “funky” because many of the sculpture were of female genitalia. (In American Negro slang “funky” means genital door.)Danny had no less than Gemma Cruz to cut ribbon and open his show.

“She was shocked when she saw the kepyas. Some looked as if crawling with bugs. But actually I didn’t make them all the obvious. They were subtle, the kepyas. And very hard work. Id buy plastic plates of various colors and melt theme with an acetylene torch, then hurry like hell sculpting them into shapes while they were soft. Then I’d attached the finished work to a wooden frame. Not all were if the female organ. This was the year after the Ruby Towers earthquake and one of my plastic sculptures looked like deck of cards crumpled, with a doll’s head tangled in wiring to suggest a child trapped in the wreckage.”

One critic noted that Dalena was the first Filipino artist to make art out of so casual and ordinary a material as plastic dinner plates. Alfredo Roces observed that Dalena had an ingredient rare in local artist: “A spirit of play, a sense of humor, a delight and excitement in what others may dismiss as inelegant materials.”

That talent for frolic would be uproariously on display again a few years later in the outlandish “sculptures” that Danny devised by filling condoms with cement.“The first show of mine I would rate as lutong luto na was in 1972, at the Solidaridad Galleries, several moments before the declaration of martial law. In this show were featured the editorial cartoons I had been doing for the Leader Magazine as well as my political sculptures and my toilet drawings. The toilet series, I started that in 1960’s, though I’d say my actual kubeta period was 1971, when I did most of the toilet pieces in 1972 show. I had long been amused by the latrines in the bistros and beerhouses I frequented, especially by the graffiti at the urinals. So I took to doing on the spot drawings of these places. If the kubeta had numerous details, I’d make studies of them and finish the composition at home. But usually I completed a kubeta sketch right there and then”

How staggered must have been those who came in to take a leak and found themselves sitting-or, rather, standing for portrait of the kubeta as forum.

Said a critic: “These quick pen-and-ink sketches of public lavatories with all manner of scribbled slogans, scurrilous epithets and provocative political graffiti, are an unsanitized gut view of bare existence, pointing to an alternative art that contradicts the notion of harmony and beauty.”

Martial law closed down the Leader Magazine and jobless Danny did his idling at the Jai-Alai, long favored haunt of his. Inevitably a new catena of works suggested itself, but the jai-Alai suite was to be far larger both in scope and dimensions than the kubeta series. From pen and ink Danny was moving to the nobler medium of oil: and from the quick sketch he was advancing to the challenge of the broad canvas.

“I must have started the Jai-Alai series in 1974 and I was lucky to become close to the Jai-Alai manager, Don Ramon Alegre, who gave me a room from which I could watch and sketch the house. I had the run of the whole place; I could poke my nose everywhere except into the pelotaris’ dugout because there I might be suspected of asking for tips. I knew all the pelotaris and they knew me but I never painted them or the game itself. What interested me was the house, the audience, the bettors. People would come in at three o’clock looking fresh and hopeful. By six o’clock they would be looking ravaged; they had lost their money, they were drunk, they felt tired and sleepy. I’d watch them hanging around aimlessly or passing out on the benches. If some character caught my eye Id shadow him all evening, observing his every move, sketching him on the sly. I was at the Jai-Alai almost every day, going there in the afternoon just before the game began and staying till closing time. Sometimes a new guard might be at the gate and he’d refuse to let me in because I was wearing wooden clogs but I’d have a bodyguard of Don Ramon Alegre called and he would vouch me.”

Danny was some four years working on his Jai-Alai suite. In 1975 the Art Association of the Philippines held a contest and Danny entered what Jai-Alai oil he had already finished. One of his paintings won the grand prize. “I was supposed to go to London but for some reason I didn’t.” What hurt was a critic complaint that AAP prize was misrewarded, said he, Dalena was, artist, a “has-been”.

The sneer but spurred Danny to complete his Jai-Alai suite so he could mount a top of hill show to disprove his being over the hill.

Art event at 1978 indeed was Dalena one-man show at the gallery of the Regent Manila. Danny found himself justified. His Jai-Alai suite was an off-fronton winner.

“There were a lot of reviews: none was adverse, all were gratifying especially the critique of the late Leo Benesa. That mine turned out to be the major show of 1978 could not but confound the carpers. The word on me now was: May ibubuga.”

It was certainly an epic effort: 27 large oil paintings, aside from a quantity of drawings.

One critic saw in this series a Dalena again going against the traditional.

“The game Jai-Alai and the premises where it is played are not traditional subjects. The masses here are far from being idealized or prettified. In this approached of art, Dalena is contrast to the studio painter who relies on tested formulas. He would prefer to go out in search of his project and Jai-Alai allows him to observe how people behave in relation to a central activity or interest. He chooses to paint the sweaty jostling masses out to win easy money. As an artist, Dalena sees people with sociological but not unsympathetic eye – his human subjects are never reduced to a pretty design or to mere visual object.”

His 1978 show won Danny recognition as a major imagist and the triumph was clinched by his winning the 1980 Mobil Art Awards, which maybe said to be the realization of the Philippine art world, two years after the event, that he canvases displayed in the Dalena Jai-Alai show were given more momentous than was unjudged at the moment.

Said one Mobil art judge of Dalena:

“If I look at his colors, they strike me as very Filipino colors – same colors I find in much of Philippine folk art. So, there are more levels in his works than in the others.”

Jai-Alai was followed by Alibangbang. The Alibangbang was a dingy beerhouse in EDSA, across the street from Farmers Market, and Danny had been a habitue there since the 1960’s, but it was in 1979 that he started doing his Alibangbang series in earnest.

“In 1975, I was teaching at the FEU and after classes I’d go to Cubao and have some beers at the Alibangbang. I liked the atmosphere: rowdy, bawdy and dowdy. The costumers were as rough and tough as the Jai-Alai clientele and the a-go-go dancers were luscious: big of bosom and rump and utterly vulgar. I tried to do some drawings but it was difficult because the place was dark.”

Then one night he recognized the one man who flashlighted new comers to empty tables as a former Student of his in drawing: Roy Vergara. Danny lost no time in enlisting Rot’s help upon learning that Roy was the son of the bistro’s owner. “Look Roy I’ve been coming here for years and I try to draw here but I can’t in this Light.” Roy said that there is only one place where Danny could both have both light and a view of the stage and audience, and was the dancers’ dressing room. That was an attic room offstage with windows overlooking the house. Danny could set up a table beside the window and there draw to his heart’s content.

“So they installed me in that dressing room and the dancers became used to my presences and were not shy about stripping and changing with me around. They’d look over my shoulder to see what I was drawing and they’d offer to pose for me, doing a dance. I was getting two views of them simultaneously; one view was of them performing on the stage and the other was of them hurrying into or out of their costumes in that crumpled upstairs room that smelled of sweaty clothes and female effluvia.

What fascinated Danny (as well as a number of eggheads who also went slumping there) was the Alibangbang welter of music, noise and good plain fun, gross and lusty but not evil, and therefore a world away from the decadence of that Berlin Cabaret where Sally Bowles hunted. The latter was a playground of the deprived; but the Alibangbang was where ordinary sensual man rollicked and roistered. It’s a virtue of Dalena Alibangbang series that it’s able to convey such differences and to suggest that certain squalor can be healthy. The Cultural Center said amen to this when, for one of its elegant posters, it picked the flamboyant vulgarity of Dalena Alibangbang stripper. The figure had true elegance.

The Alibangbang series went on show in 1981, at the Alegria Gallery, and once again Danilo Dalena was the toast of the art world.

“In this series,” ran one comment,” his colors showed a greater vibrancy and his lines a more optimistic lift. Both the Alibangbang and the jai-Alai series are made memorable by Dalena’s unique style of portrayal of character.”

For Danny himself the Alibangbang show was memorable because “some of my works were bought.” A name in art circles, he was not like Legaspi or Bencab, a name in the art market. Danny is rather touchy about this and refuses to reduce any history of his art to a gross receipt of earnings and profit, or to a market report on how much the product was, or was not sold. But his crowd knows he lives among his leftovers – for example, the outrageous condoms thingumajigs (for which he reported used a thousand rubbers) which he now gives a paper-weight, but only to his barkada and his crowd has remained steady through the years: Recah Trinidad, Erwin Castillo, Pepito Aguila, Pete and Mara Lacaba, Greg Brillantes, Joe Carreon, and a certain old fogeys who shall be nameless. Inevitable again after Alibangbang series was a barkada suite, composed of the portraits of the above-named cronies, whose images hung for years on the walls of Danny’s home latrines. In 1988, he took out the dishonored countenances for a much needed-airing and exhibited them on the Finale Art File in Show titled: “Friends and other landscape.”

The crony faces mostly provoked hilarity among the voyeurs. Of more serious interest were the landscapes because they showed whither Danny had been gravitating for some time now: towards his Laguna hometown of Pakil.

Pakil is famous for its rites in honor of Our Lady of Sorrows. Almost yearlong is this cult of the Turumba, beginning on the Viernes de Dolores (the Friday before the Palm Sunday) and culminating with the feast of the Transfixion of Our Lady on September 15. In between are series of novenas, each series forming a lupi, or “fold”’ that’s marked with procession of the Dolorosa.

Danny found himself drawn more and more to the Turumba as well as to the other customs of his native town. Presently he was spending weekends, or even entire weeks, in Pakil, where Dalena stone house stands on the plaza and is the “home” of the town’s patron saint, for the Dalena’s is traditionally the caretakers of the image of Saint Pedro de Alcantara. Whenever his barkada barkada missed Danny at their usual haunts the world would go around that the artist had gone home to Pakil again and wonder would be expressed at the growing frequency of his vanishings.

Danny says he would suddenly feel desire to be Pakil and on the instant he would arise and go.

“It’s like the pull of gravity: parang namamagneto ako. I don’t only go there to paint. Sometimes I’m not doing anything but wander around, observing the life in Pakil – but I’m painting in my mind. I’d comeback to manila and almost immediately I’d be hurrying back to Pakil again. That’s how it was for four years I was able to finish 24 painting of the old church; of the komedya and moro-moro; of the Virgin’s devotees throwing water at each other or washing themselves in the mountain spring; of hick drunks making scene. I like the rude and riotous; I don’t like the cute. Up to now my Pakil series isn’t finished yet. It’s a continuing project, a work ever in progress.

Danny knows what he’s really doing: he is becoming a true Pakil townsman- which he wasn’t before, being so thoroughly manileño.

“I was born in Pakil but after Grade 3 I was transferred to Manila, to keep my mother company. My father, who was a lawyer and notary public, stayed in Pakil but had to be in Manila because my sisters were studying in the city. So, from age nine I have been a city boy. We only went Pakil on summer vacation.”

He was, you might say, immerse in art all through childhood because of his obsession in comic books: the tagalog komiks were his first art teachers. “I was such an avid komiks reader I was able to collect three drums full of classic illustrated and Batman and Superman and Captain Marvel. That was when I started drawing, copying the figures in the comic books. I was ten years old then, still in short pants; the popular singer was Patti Page and the pop song were How much is that Doggie in the Window and a Beautiful Brown Eyes.”

In high school he got out of PMT by pretending to be deaf and then found that he was really going deaf.

“Always, from the grades on, I was class first the one the teacher called to draw in the black board, the one who did the sketches for biology class, the one picked as illustrator of the school organ. So, when ready for college, I told my parents I want to study fine arts, at the UST, and they said okay. I took up advertising arts with an elective course in painting, but in never tried oil there. My professor were Edades, Galo Ocampo and in graphic arts Cenon Rivera, who had the Varsitarian take me on as art editor so from my second year, I was enjoying free tuition. I graduated in 1965 and after short stints at an ad agency and a printing firm, I applied at the Free Press Magazine. The art director, Izzie Izon, made me illustrate a short story. That was my testing: That double spread illustration to appear in the Free Press. And I was hired.”

Danny would at that time fall in with the gang of writers and artist whose influence would transform him into bohemia. His gypsy style has since jelled into uniform, as follows:

Footwear: Always bakya. Pants: always maong. Shirt: either rugged t-shirt or crumpled camisachino. Hair: worn very long in braids ponytail, topknots, or a dangle. Facial Fur: Mustaches, sideburns, chin brittles. Headgear: always a balangot sombrero, discolored and much crushed. Extra gear: hearing aid, shopping bags, rolled up posters.

He keeps a jukebox in his sala and has a terrific selection of Frankie Sinatra, Cole Porter, Barbara Streisand and Broadway-Show records. He loves sauces.

The idea of a big Dalena retrospective at the Cultural Center when the idea was first broached. But when he died the show was still a cooking. Those who succeeded him invited me again to exhibit at the Cultural Center, time of Imelda but again the thing didn’t push through. The third invitation was already in the time of Cory, when he came, Nic Tiongson and company to the cultural Center, and Nic Tiongson was among those who really pushed to get my show going. The trouble was that there were two invitations. The first was for me to join the show of expressionists. But I have never considered myself an expressionist: other pin that tag on me and I’d be called me bingegot. Happily the other invitation was for a Dalena retrospective. That I approved. And I assured them: this will go through, in 1990, on August 15, Assumption Day, Baclaran Day.”

This will be his artistic autobiography.

“It’s a review of my work from 1970 to the present. All my work together. Included will be toilets, the political cartoons, the Jai-Alai, the portraits, the Alibangbang, tha Pakil oils and maybe even the Quiapo Ilalim series though perhaps only eight pieces of it: if I can borrow the paitings of the procession and of the underpass.”

“In Pakil series I am expressing my love for my hometown but I don’t want it to be maudlin or seryoso. As I did it, it’s lighthearted fun, katuwaan a laughing salute to the place, even a joke on it. It’s not my habit to close my eyes to whatever is laughable about what is love.”

The focus is on roots.

“My childhood in Pakil, our house there in the middle of the plaza, facing the church, facing the municipio: puro katapat, tapat ng Rizal monument, tapat ng World War II Canon, tapat ng grandstand, tapat ng Sierra Madre. We are really and have always been, in the midst of it all. My father was town mayor during the war. My childhood was beautiful: I had the bacony seat for all the town happenings. During fiesta, or procession, or theater on the plaza, we didn’t have to leave the house. We can watch it all from our window and balconies. I grew up in jukebox music because my mother had a business of juke boxes for rent. We were 9 siblings, four girls and five boys, but our junior died young. An uncle of mine run a barber shopin our basement: when he died he turned the barberia into a komiks store. When I’m In Pakil I fine many plenty of time to observe the world. I watch people working and people idling; I even watch the dogs. Sa probinsiya talagang maluwag ka sa oras, lagi kang may panahon manood. If you collect those red pupl horses and carabaos, there are hundreds of then on our patio on October 19, which is our fiesta, the day of our patron San Pedro de Alacantara. But as the red letter day in Pakil is September 15, feast of the Seven Sorrows of Virgin, when we celebrate the last Turumba of the year. I’m always home for those celebration and also for Holy week, And Maytime, and All Saints Day, and Christmas. I discovered so many things in Pakil, I learned so much there. Maybe that’s why the town has me so magnetized. And why I’ll never be through with my Pakil series. I started that series because naramdaman ko na gusto ko ng umuwi ng Pakil kasi gano’n ang gusto kong pakiramdam. You know, magnetized.”

Danny Dalena, welcome home.

ONE-MAN SHOWS

1969 Oil Paintings, Joy T. Dayrit’s Print Gallery Plastic Sculptures, Northern Motors showroom

1972 Editorial Cartoons, Toilet Drawing and Plastic Scupltures, Solidaridad Galleries

1978 Jai-Alai Series of Drawings, Sining Kamalig at the Regent Manila

1979 Works by Dalena, Sculptures in Terra Cotta & Cement

1981 Alibangbang Paintings & Drawings, Alegria Gallery

1984 Pakil Series, Paintings, Pinaglabanan Galleries

1988 Friends and other Landscapes, Portraits, Finale Art File

1963 Pax Romana Religious Art Exhibition, University of Sto. Tomas

1964 Shell Annual Art Exhibit, National Library

1965 Society of the Philippine Illustrators & Cartoonist Exhibit, National Press Club Building

1966 Art Directors Club of the Philippines Art Show, Northern Motors Showroom

1969 “Words and Pictures”, Joy T. Dayrit’s Print Gallery

1970 Young Talents, Art Association of Philippines Gallery “The Artist in revolt” Solidaridad Galleries Summer Exhibition, Cultural Center of the Philippines

1971 Society of the Philippine Illustrators & Cartoonist, Ayala Art Show, Hotel Intercontinental Manila

1972 Thirteen Artist, Cultural Center of the Philippines

1974 Shop Six, Sining Kamalig

27th Art Association of the Philippines Art Show, Ayala Museum Buklatan, Cultural Center of the Philippines

1975 Shop Six, Sining Kamalig

Shop Six Silangan Gallery

Shop Six Cultural Center of the Philippines,

Shop Six Sining Kamalig

1978 CCP Annual, Cultural Center of the Philippines

1979 Art Fiesta, Sining Kamalig

Wood Works Small Gallery, Cultural Center of the Philippines

Art Association of the Philippines- Abbott Lighter Sculpture Show, Philamlife Hall Cultural Center of the Philippines

1980 Art Association of the Philippines First Prize Winner, Cultural Center of the Philippines

AAP Artist, Philippine International Convention Center

Fiber Works, Sining Kamalig

International Festival of Painting, Haut De CAgnes, France

Philippine Art, Fukouka Museum, Japan

1963 First Prize, Painting Pax Romana Religious Art Competition

1964 Second Prize, On the Spot Painting, Shell Company of the Philippines

1965 First Prize, Color Illustration, Society of the Philippine Illustrators & Cartoonist Art Competition

1966 Award of Distinctive Merits, Art Association of the Philippines

1970 Young Talents, Art Association of the Philippines

1971 First Prize, Graphic Arts, Society of the Philippine Illustrators and Cartoonist- Ayala (SPIC-AYALA) Art Competition

Second Price, Editorial Cartoon, SPIC-AYALA

First Honorable Mention, Editorial Cartoon, SPIC-YALA

1972 Awardee, Thirteen Artist Awards

1974 First Prize, Painting, 27th Art Association of the Philippines Annual Art Association

1979 Fourth Price, Art Association of the Philippines-Abbott Lighter Sculpture Competition

1980 Grand Awardee, 1980 Mobil Awards for Philippine Art

CATALOGUE OF WORKS

PORTAIT OF PUNAY

Oil

89 x 73.5 cms.

Gloria Caccam Collection

PORTRAIT OF JOY

Oil

90 x 60 cms.

Gloria Caccam Collection

PORTRAIT OF GLORIA

Oil

84 x 60 cms.

Gloria Caccam Collection

NUDE

Ink

34 x 47 cms.

Gloria Caccam Collection

KATALO

Oil

84 x 61 cms.

Nestor Mata Collection

PALABAS NG LAWA

Oil

44.5 x 61 cms.

Erwin Castillo Collection

PORTRAIT OF ERWIN

Oil

46 x 61 cms.

Undated

Erwin Castillo Collection

PORTRAIT OF MARCELO

Oil

91 x 90 cms.

1986

Gilda Cordero Fernando Collection

PORTRAIT OF TIA NATY

Oil

61 x61 cms.

1982

Nick Joaquin Collection

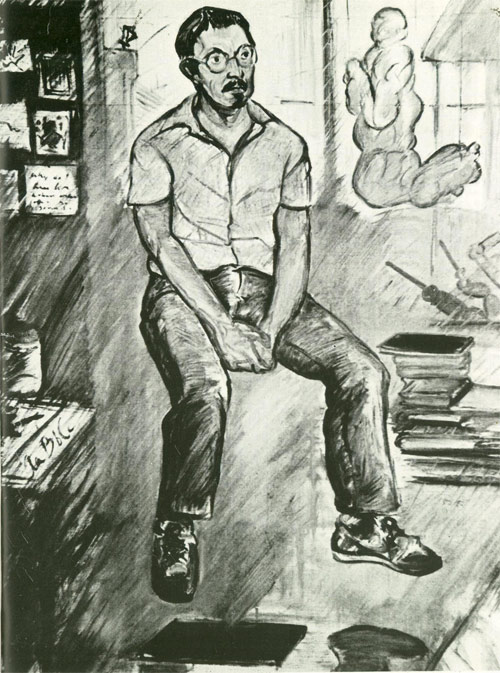

SELF PORTRAIT

Ink

38.5 x 42.5cms.

Undated

Nick Joaquin Collection

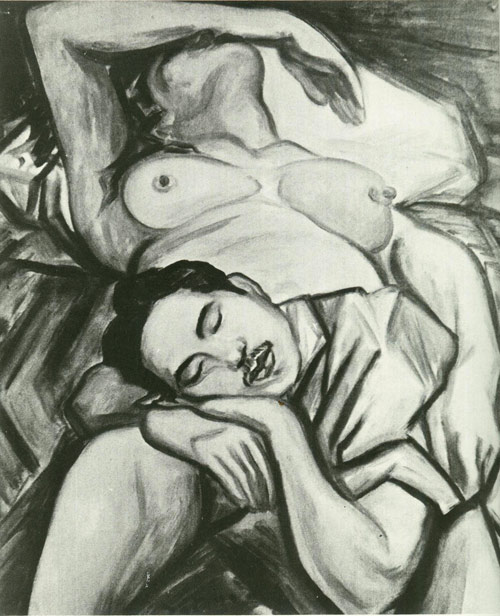

TULOG-TULOG

Oil

54.5 x 70 cms.

1983

Maria Rivera Coronel Collection

PORTRAIT OF RECAH

Oil

45.5 x 60 cms.

1981

Recah Trinidad Collection

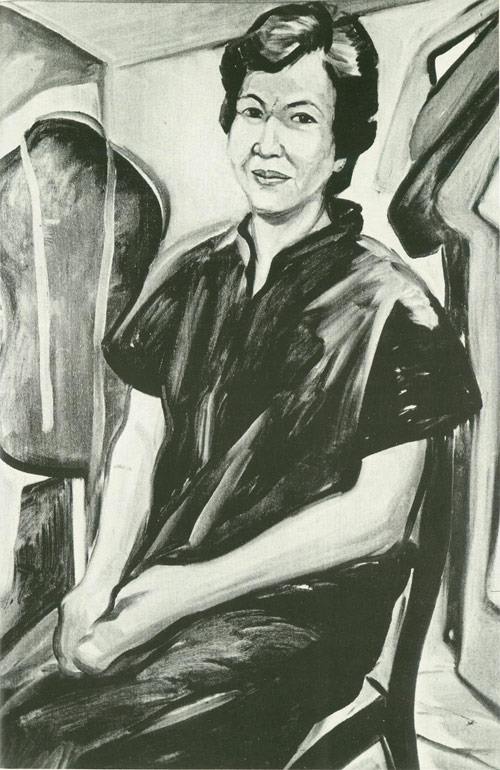

PORTRAIT OF FE LACSAMANA

Oil

55.5 x 42 cms.

1982

Recah Trinidad Collection

PORTRAIT OF PEPITO

Oil

46 x 61 cms.

1981

Pepito Aguila Collection

TALUHAN

Oil

49 x 58 cms.

1975

Pepito Aguila Collection

PORTRAIT OF CRIS

Oil

56 x 72 cms.

1988

Cris Michelena Collection

TURUMBA SA PAKIL

Oil

182 x 152 cms.

1984

Michael Adams & Agnes Arellano Collection

REVIEW NO. 2

Oil

61 x 61 cms.

Marilies & Peter Von Brevern Collection

PAYAO

Oil

50 x 67.5 cms.

Marilies & Peter Von Brevern Collection

PAYAO

Ink

12.4 x 18.5 cms.

1983

Marilies & Petern Von Bevern Collection

ALTAR NG PAKIL

Oil

61 x 44.5 cms

1987

Dr. Carlos P. Reyes Collection

POPORTRAIT OF CARLOS

Oil

91.5 x 76 cms.

1987

Dr. Carlos P. Reyes Collection

LUBID

Oil

116 x 68.5 cms.

1989

Jose Quiros Collection

BANGUNGOT

Oil

61 x 76 cms.

1983

Franz Arcellan Collection

CATNAP

Mixed-media

15 x 23 cms.

1981

Franz Arcellana Collection

PORTRAIT OF NORMA

Oil

61 x 91.5 cms.

Norma Liongoren Collection

FEMALE NUDE 4

Ink

53 x 43.5 cms.

1972

Norma Liongoren Collection

LAST CALL TO PLACE YOUR BET

Oil

75 x 151 cms.

1977

Betty Go-Belmonte Collection

TULOG-TULOG

Oil

49 x 66 cms.

1977

Angie Rodriguez Collection

TATLONG BAKANTE

Oil

23.5 x 23.5 cms.

1981

Angie Rodriguez Collection

PORTRAIT OF DING

Oil

88 x 72 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF NICK

Oil

95 x 122 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF BOBBY

Oil

95 x 122 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF JOY DAYRIT

Oil

65 x 51.5 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PANGHULO

Oil

152.5 x 183 cms.

1984

Artist Collection

COMEDIA SA PAKIL

Oil

152.5 x 183 cms.

1990

Artist Collection

UNDERPASS

Oil

89 x89 cms.

Artist Collection

ASONG SIMBAHAN

Oil

152.5 x 183 cms.

1984

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF BOBBY

Oil

90 x 90 cms.

1989

Bobby Tuason Collection

PORTRAIT OF INDAY LEE

Oil

65 x 52 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF TONY AUSTRIA

Oil

73 x 57.5 cms.

1982

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF CHIQUI

Oil

57 x 44 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF MANG TANO

Oil

71 x 96 cms.

1987

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OD TIYO KUNE

Oil

57 x 44 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF FRANZ AND HIS 1,000 WATT BULB

Mixed-media

71 x 56.5 cms.

1988

Artist Collection

PAPA

Oil

83 x 53 cms.

1988

Artist Collection

ASONG GALA

Oil

152.5 x 152.5 cms.

1984

Artist Collection

PLASTIC COVER

Oil

93 x 120 cms.

1983

Artist Collection

SCARECROW CHRIST

Oil

120.5 x 96.5 cms.

1970 Artist Collection

TALO

Oil

43 x54 cms.

1976

Artist Collection

OFF-FRONTON

Oil

75 x 120 cms.

1977

Artist Collection

SPECIAL LLAVE

Oil

91.5 x 183 cms.

1978

Artist Collection

BOMBA

Oil

91.5 x 183 cms.

1990

Artist Collection

SIMBAHAN

Oil

95 x 120 cms.

1975

Artist Collection

BREAKTIME

Oil

42 x 51.5 cms.

1978

Artist Collection

SUKA

Oil

68 x 64 cms.

1978

Artist Collection

IHING TALO

Oil

98 x 72 cms.

1976 Artist Collection

MAN BEHIND THE SCOREBOARD

Oil

75 x 100 cms.

1977

Arstist Collection

TALO

Oil

60 x 85 cms.

1989

Artist Collection

TULOG-TULOG

Oil

75 x 100 cms.

1975

Artist Collection

SKYROOM

Oil

93 x 181 cms.

1977 Artist Collection

KRISTO

Oil

44 x 100 cms.

1974

Artist Collection

MGA TALUNAN

Oil

84 x 60 cms.

1989

Jose Quiros Collection

ALIBANGBANG

Oil

61 x 76 cms.

1989

Jose Quiros Collection

GUTOM

Oil

35.5 x 61 cms.

1981

Angie Rodriguez Collection

MOTHER & CHILD

Oil

61 x 61 cms.

1981

Paulino Que Coleection

ESTACA

Oil

91 x 91 cms.

1987

Ambeth Ocampo Collection

PORTRAIT OF AMBETH

Oil

35 x 44.5 cms.

1986

Ambeth Ocampo Collection

PORTERYA

Oil

150 x 150 cms.

1984

Armando Eduque Collection

CAT WITH NINE LIVE SHOWS

61 x 85 cms.

1981

Armando Eduque Collection

ALIBANGBANG NO. 1

Oil

36 x 60 cms.

1981

Private Collection

DOM

Oil

34 x 53 cms.

1984

Private Collection

THREE MINUTES TO ONE

Oil

120.5 x 95 cms.

1976

Bnn C. Bautista Collection

DANCING BOOTS

Oil

91.5 x 91.5 cms.

1981

Alex Tee Collection

ESTACA

Oil

55 x 60 cms.

1987

Liza Tee Collection

PORTRAIT OF AL

Oil

45 x 60 cms.

1983

Alfonso S. Mendoza Collection

PORTRAIT OF SOL

Oil

45 x 60 cms.

1984

Alfonso S. Mendoza Collection

SAYAW ALIBANGBANG

Ink

12.7 x 19 cms.

1979

Alfonso S. Mendoza Collection

GAME OVER OR TALUNAN

Oil

90 x 90 cms.

1984

Private Collection

TULOG-TALO

Oil

66 x 66 cms.

1984

Private Collection

PORTRAIT OF CORAZON

Oil

56 x 80 cms.

1985

Atty. Francisco Serrano Collection

PORTAIT OF MARRA

Oil

60 x 60 cms.

Undated

Private Collection

Mang Pin

Ink

22.5 x 30 cms.

1982

Private Collection

ALING ORIANG

Mixed-media

27 x 21 cms.

1983

Private Collection

TABLE NO. 1

Oil

61 x 76 cms.

1990

Bobby Tuason Collection

PORTRAIT OF FRANCISCO

Oil

90 x90 cms.

1985

Atty. Francisco Serrano Collection

BAKANTE NO. 2

Oil

84 x 59.5 cms.

1989

Bobby Tuason Collection

SEIS DEJADO

Oil

60 x 35.5 cms.

Bobby Tuason Collection

TRES LLAMADOS

Oil

25.5 x 58 cms.

1984

Bobby Tuason Collection

JAI-ALAI FRONTON

Oil

29.5 x 44.5 cms.

1984

Bobby Tuason Collection

CATNAP 2

Oil

36 x 60 cms.

1984

Bobby Tuason Collection

LASING

Mixed-media

23 x 13.5 cms.

1981

Bobby Tuason Collection

MALE NUDE

Ink

19 x 13 cms.

1983

Bobby Tuason Collection

MANINILIP

Oil

117 x 69 cms.

1981

Artist Collection

GENTLEMEN

Oil

168 x 117 cms.

1990 Artist Collection

SA BIRHEN

Oil

89 x 89 cms.

1996

Artist Collection

PAKIL ALTAR

Oil

47 x 61 cms.

1983

Artist Collection

LAST SUPER SA ESTANTE

Oil

152.5 x 186 cms.

1984

Artist Collection

PAMBALOT

(series of 3 frames)

BUHAY ASO

Oil

60 x 60 cms.

1983

Artist Collection

PAKIL CACTUS

Oil

58.5 x 53 cms.

1990

Artist Collection

PADAPIT-HAPON

Oil

55 x 60 cms.

1987

Artist Collection

TATLONG MARIA NI JESUS DANILO (series of 3 frames)

Oil

40 x 38 cms. Each

1981

Artist Collection

PORTRAIT OF LULING OLYMPIA

Oil

69 x 118 cms.

1984

Artist Collection

KA VIVIAN

Oil

58 x 58 cms.

1983

Artist Collection

Maninilip (1981)

Alibangbang (1981)

Dancing Boots (1981)

Katalo (1981)

Lasing (1981)

Mother and Child (1981)

Catnap 2 (1989)

Dom (1984)

Bakante No. 2 (1989)

Alibangbang (1989)

Table No.1

Gutom (1981)

Man Behind the Scoreboard (1977)

Special Llave (1977)

Off Fronton (1978)

Last Call to Place Your Bet (1977)

Review No. 2 (1989)

Game Over (1984)

Mga Talunan (1989)

Tulog-Talo (1984)

Seis Dejado (1989)

Tres Lllamados (1984)

Bomba (1990)

Talo (1989)

Mga Batang Nazareno (1979)

Plastic Cover (1983)

Simbahan (1975)

Turumba sa Pakil (1984)

Asong (1984)

Sa Birhen (1986)

Panghulo (1984)

Buhay Aso (1983)

Payao (1983)

Comedia sa Pakil (1990)

Portrait of Luling Olympia (1984)

Portrait of Nick (1981)

Portrait of Bobby (1981)

Portrait of Al (1983)

Portrait of Corazon (1985)

Portrait of Ambeth (1986)

NOTE: Printed in 1990 by EXCEL Printing Press, this catalogue was spearheaded by the Coordinating Center for Visual Arts (CCVA-CAMP) of the Cultural Center of the Philippines.