By the Artesdelasfilipinas Research Team

Introduction to the Murillo Velarde Map

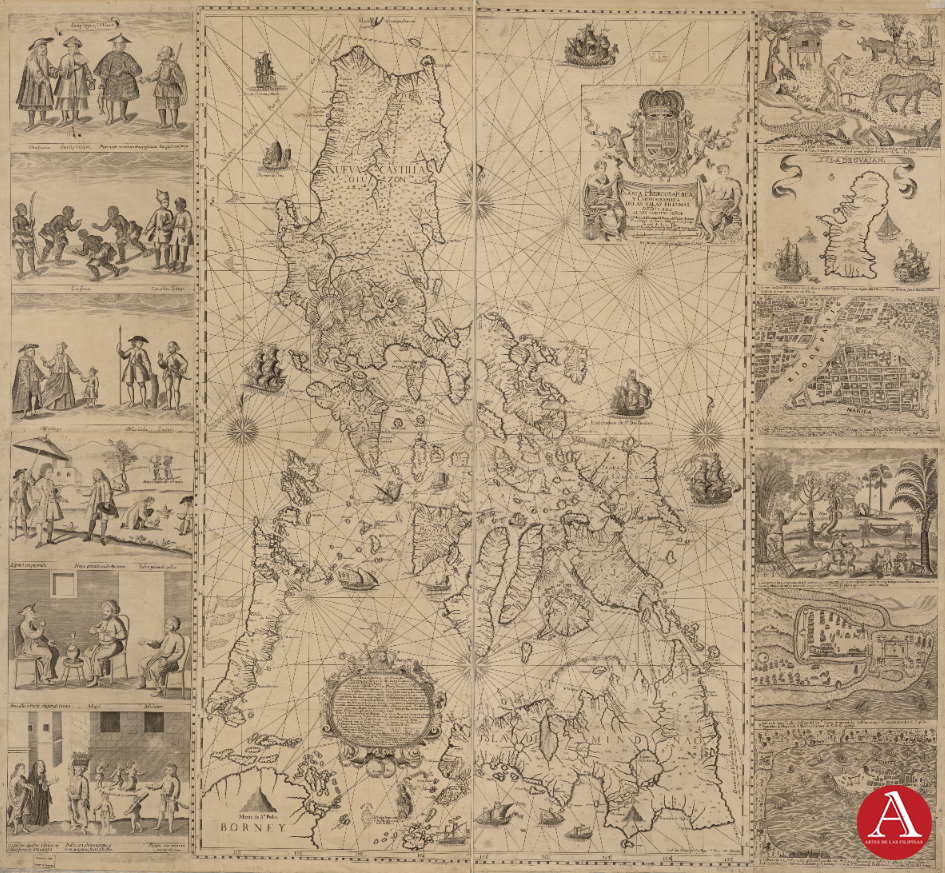

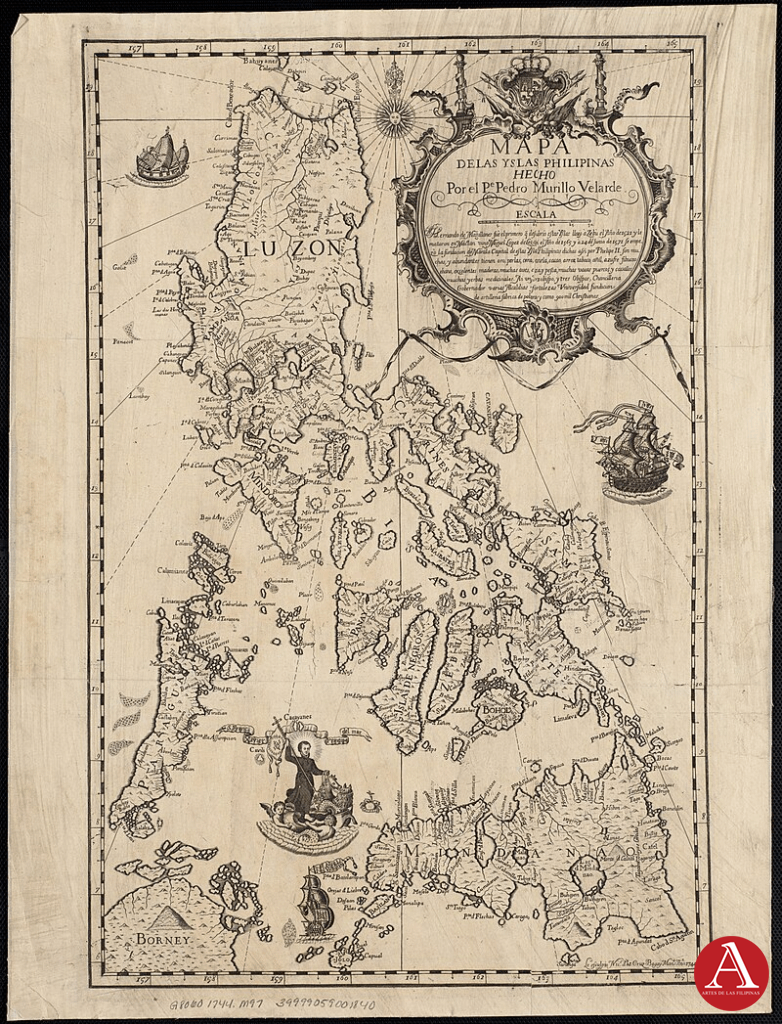

The Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Islas Filipinas of 1734, more commonly known as the Murillo Velarde map, is considered the first comprehensive and scientifically grounded map of the Philippine archipelago. Produced under Spanish colonial administration by Jesuit cartographer Pedro Murillo Velarde, with the collaboration of Filipino artist Francisco Suárez and engraver Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay, it occupies a singular place in both the history of cartography and the cultural heritage of the Philippines. Beyond its technical achievement, the map serves as an enduring artifact that intertwines colonial knowledge production with local artistic expression.

Colonial Cartography and Knowledge Production

The Murillo Velarde map represents a landmark in eighteenth-century cartography. At a time when European empires sought increasingly precise geographic data to facilitate trade, navigation, and governance, this chart provided the most accurate and detailed representation of the Philippine islands available to contemporaries. It incorporated coastlines, ports, and maritime routes—including the trans-Pacific galleon route between Manila and Acapulco—thereby positioning the Philippines firmly within global trade networks. Its scale, detail, and visual clarity made it a standard reference for later cartographers across Europe, influencing geographic representations of the archipelago well into the nineteenth century.

The map also reflects the collaborative dimensions of colonial knowledge-making. While sponsored by colonial authority, its execution required the skills of local artisans and the integration of indigenous spatial knowledge. The involvement of Suárez and Bagay demonstrates how Filipino artistry and craftsmanship contributed directly to the production of what became a canonical piece of cartographic scholarship. This hybridity marks the map as a cultural product of both European scientific traditions and local intellectual labor.

Ethnographic and Cultural Representation in the Murillo Velarde Map

What distinguishes the Murillo Velarde map from many contemporary European charts is the presence of twelve vignettes, engraved on its margins, illustrating diverse peoples and cultural practices in the archipelago as well as two beautiful cartouches. These depictions include representations of various ethnolinguistic groups, settlers of mixed ancestry, seafarers from other parts of Asia, and indigenous communities. In addition, inset maps highlight major settlements such as Manila, Zamboanga, and Cavite, as well as neighboring territories like Guam.

These illustrations provide valuable insight into eighteenth-century conceptions of social diversity in the Philippines. Though filtered through colonial lenses, they nonetheless document the multi-ethnic composition of the islands and the range of occupations, attire, and lifeways that characterized daily existence. As such, the map functions not only as a geographic tool but also as a cultural and ethnographic record, capturing the plurality of identities within the archipelago.

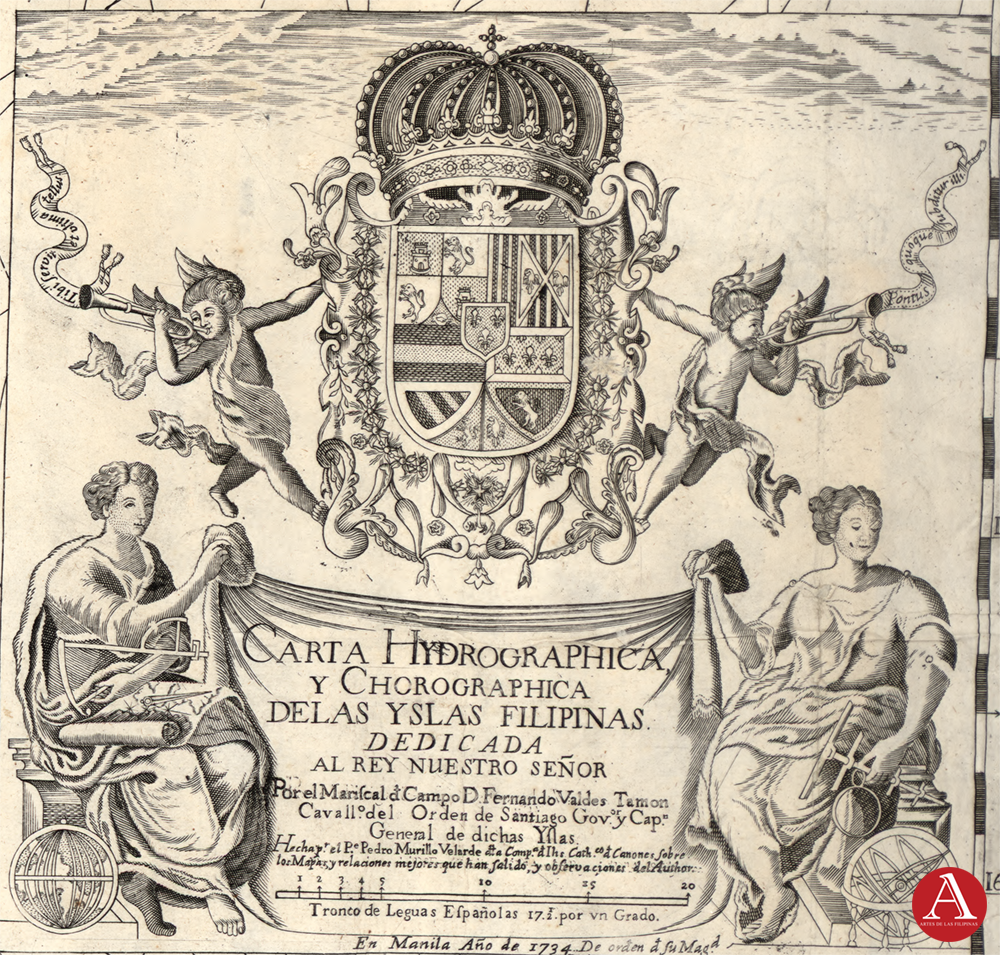

Title Cartouche

The cartouche of Murillo Velarde map of the Philippines is one of its most symbolically rich features, combining art, science, and politics. At its center is Spain’s royal coat of arms, crowned and supported by cherubs, signifying the Philippines’ place under Spanish imperial authority. This visual affirmation of sovereignty is framed by allegorical female figures representing Science and Geography, highlighting the Enlightenment ideals of exploration, measurement, and knowledge that underpinned both empire and cartography.

The dedication explicitly offers the map to the Spanish king, positioning it as both a scientific document and an imperial instrument. Authorship is also acknowledged, crediting Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde as the primary author, with Francisco Suárez as the artist and Filipino engraver Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay executing the work—underscoring the collaborative nature of its production and the role of local talent in a globally significant artifact.

The cherubs (putti) blowing trumpets and holding scrolls symbolize proclamation, knowledge, and authority, reinforcing the political function of the map. Ultimately, the cartouche reveals how mapping in the 18th century was not a neutral activity: it was a convergence of Enlightenment science, Jesuit scholarship, and Spanish imperial power.

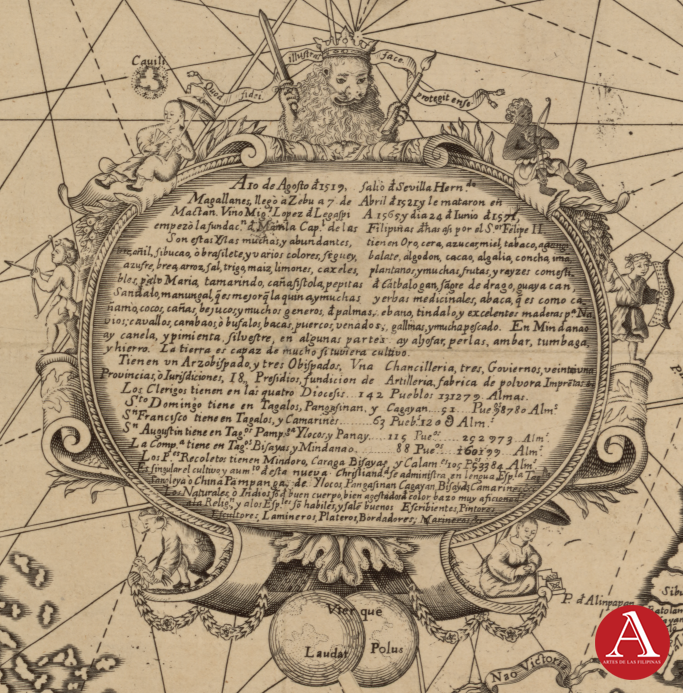

Historical and Descriptive Cartouche

This inscription narrates the Spanish discovery and colonization of the Philippines, beginning with Magellan in 1521 and the founding of Manila by Legazpi in 1565. It describes the islands’ natural wealth—gold, spices, fruits, timber, and livestock—emphasizing their fertility and abundance. The text also details the colonial administration and ecclesiastical structure, highlighting the number of provinces, dioceses, towns, and population under various religious orders. Finally, it praises the Filipino natives for their skills, intelligence, and adaptability in crafts, trades, and the arts, framing them as industrious subjects of the Spanish crown.

Translation

In the year 1519, Hernando de Magallanes (Magellan) departed from Seville and in April 1521 arrived at Cebu, later dying in Mactan. In 1565, Miguel López de Legazpi began the foundation of Manila, capital of the Philippines, under King Philip II.

These islands are numerous and abundant, rich in gold, wax, sugar, tobacco, rice, cotton, cacao, indigo, ginger, pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, palm, coconut, timber (such as ebony and tindalo), and many fruits and roots like bananas, guava, tamarind, and camote. They also produce pearls, amber, tortoiseshell, and iron. The land supports large herds of cattle, buffalo, horses, pigs, goats, deer, and poultry, providing ample meat.

The archipelago has one Archbishopric, three Bishoprics, a Chancellery, three Governments, and 21 Provinces or jurisdictions. There are 18 presidios (forts), a foundry for artillery, a gunpowder factory, and a printing press. In the four dioceses there are 142 towns with 331,279 souls.

- The Dominicans serve in Tagalog, Pangasinan, and Cagayan (51 towns, 98,780 people).

- The Franciscans in Tagalog and Camarines (63 towns, 120,000 people).

- The Augustinians in Tagalog, Pampanga, Ilocos, and Panay (112 towns, 292,973 people).

- The Jesuits in Tagalog, Visayas, and Mindanao (88 towns, 160,019 people).

- The Recollects in Mindoro, Caraga, Visayas, and Calamianes (25 towns, 52,384 people).

The natives (Indios) are described as of good build, well-formed, and brown-skinned, clever and skilled in arts and trades. They are noted as excellent scribes, painters, silversmiths, embroiderers, sailors, and musicians.

Left Map Panels

The left panel of the Murillo Velarde map portrays the Philippines as a cosmopolitan hub, depicting Chinese merchants and laborers, Africans, Indian Ocean sailors, mestizos, Mardicas, Japanese, Spaniards, creoles, indios, and upland Aetas within a clear colonial social hierarchy. Alongside foreign traders from Armenia, Persia, India, and Malabar, it also highlights everyday Filipino life—from churchgoing and farming to cockfighting and dancing—blending images of global trade, migration, and indigenous tradition.

Sangleyes, ó Chinos

This panel is a vignette illustrating Chinese inhabitants in Manila, often referred to as Sangleyes (from the Hokkien word seng-li, meaning business or commerce). The engraving depicts four distinct figures, each labeled with a description that highlights their role or social standing:

- Christiano (Christian Chinese) – On the far left, dressed in a long robe and hat, this figure represents a Chinese immigrant who had converted to Christianity. Conversion was strongly encouraged by Spanish authorities, and Christianized Chinese were often granted more rights and protections.

- Gentil principal (Principal Gentile/Pagan Chinese Elite) – Next to him stands a figure in a fine robe holding a fan, representing a non-Christian, high-ranking Chinese individual. This underscores the presence of wealthy merchants and leaders among the Sangley community in Manila.

- Pescador con chanchuy y falacot (Fisherman with fish and raincoat) – The third figure is dressed in a shaggy raincoat made of plant fiber (salacot hat and palm-fiber cape), holding a fish in one hand. This depicts an ordinary working-class Chinese fisherman, emphasizing their contribution to food supply and manual labor.

- Cargador con pinga (Carrier with load) – On the far right, a laborer carries a shoulder pole (pingga) used for transporting goods. This figure symbolizes the Chinese as essential carriers, porters, and workers in colonial Manila’s economy.

Together, this vignette presents a spectrum of the Chinese community in the Philippines—from Christianized elites to common laborers. It reflects both their economic importance and the Spaniards’ attempt to categorize them according to religion, class, and occupation.

Cafres, Canarín and Lasear

On the left side are the Cafres, shown as four figures with curly hair, dressed in short skirts or loincloths, and adorned with bead-like ornaments around their legs. One holds a bow, underscoring their association with hunting or warrior activities. Their postures are dynamic and active—two are crouched forward as if ready to move or attack, while another gestures outward with an extended arm. The term Cafres, derived from the Arabic kafir (“non-believer”), was used by Spaniards to describe Africans, many of whom arrived in the Philippines as enslaved individuals through Portuguese and Spanish colonial trade networks. It is noteworthy that the mythological Kapre of Filipino folklore may have originated from or been influenced by the Cafres of colonial times.

On the right are the Canarín and Lasear. These two men stand apart from the Cafres, and their attire suggests higher status or different roles. One is dressed in a long robe with a distinctive hat, which may signify an official, religious, or specialized position. The other wears simpler clothing but still reflects a non-local Asian identity. Canarín likely refers to people from the Canary Islands, while Lasear is associated with Lascars, the South or Southeast Asian sailors who served on Portuguese and Spanish ships.

Together, this vignette highlights the ethnic diversity of Manila and its wider maritime connections in the 17th and 18th centuries. Africans (Cafres) were often brought as enslaved laborers, while Canarins and Lascars came as sailors and workers drawn from Spain’s extensive colonial and trade networks across Africa, India, and the Indian Ocean. By placing these figures side by side, the map underscores the Philippines as a cosmopolitan hub of the Spanish Empire, where people of diverse backgrounds—European, African, and Asian—converged, though often under unequal colonial conditions.

Mestizos, Mardicas, and Japon

On the left, we see a well-dressed family labeled “Mestizos.” The man wears a European-style hat, coat, and stockings, while the woman dons a long skirt and blouse with intricate details, holding the hand of a child also in European attire. This imagery reflects the mestizo class — people of mixed indigenous and foreign (often Spanish or Chinese) ancestry — who occupied an increasingly important place in colonial Philippine society. Their clothing and demeanor emphasize social status, refinement, and assimilation into Hispanicized culture.

To the right, two figures represent other groups: “Mardica” and “Japon.” The Mardica, descendants of Christianized natives from the Moluccas resettled in the Philippines by the Spanish, is shown carrying a spear and dressed in simple but functional clothing, symbolizing their role as loyal auxiliaries in colonial defense and settlement. Beside him stands the “Japon,” a figure representing early Japanese migrants or their descendants in the Philippines, recognizable by simpler garments and a distinct hairstyle. Their inclusion highlights the Philippines’ multicultural society in the 18th century, shaped by migration, trade, and colonial policy.

Spanish-Colonial Philippines Social Hierarchy (18th Century)

The composition shows a variety of figures representing the social and cultural order of the time. On the left, a Spaniard with parasol (Español con payo alto) stands in elegant European dress, shaded by a servant, a symbol of privilege and authority. At the center is a dark-skinned creole of the land (Negro atezado criollo da tierra), also clothed in European fashion but signifying a lower position in the colonial hierarchy, known also as “Insulares” or Spanish born in the Philippines. To the right, two indios (Filipinos with Austronesian ancesrty) engage in cockfighting (indios peleando gallos), an activity with deep pre-Hispanic roots that endured as a popular pastime under Spanish rule. In the background, two Aetas or Cimarrones del monte are depicted with bows and arrows, representing upland indigenous groups who lived beyond colonial control.

Together, these figures illustrate the social hierarchy of the Philippines under Spain. Spaniards, creoles, and mestizos (mixed race) occupied higher ranks, while indios, and indigeneous peoples filled subordinate or marginal roles. The inclusion of cockfighting emphasizes how certain cultural traditions thrived across class boundaries, even becoming a source of colonial revenue through gambling regulation.

Manila Trade Partners in the 18th Century

The panel reflects the global commercial connections of Manila in the 17th–18th centuries, when the city was a crossroads of the Spanish empire’s trans-Pacific galleon trade. Merchants from Armenia, Persia, India, and beyond converged in the Philippines, supplying Asian goods for exchange with American silver. The depiction of these figures in European-style engravings underscored Manila’s role as a meeting point of diverse peoples and cultures. The inclusion of a Persian smoking a hookah also highlights the diffusion of cultural practices—such as tobacco use—across empires via trade.

- Left: Armeño o Persa chupando tabaco (“Armenian or Persian smoking tobacco”). The man is seated on a chair, smoking a hookah or water pipe, which had spread from Persia and India across Asia and into the Philippines by the 17th century. His attire, long robe and distinctive headgear, identifies him with the Middle Eastern or Central Asian merchant communities that were active in Manila. Armenians and Persians played important roles as intermediaries in trade, especially in silks, spices, and luxury goods.

- Center: Mogol (“Mughal”). This figure represents someone from the Mughal Empire of India, a powerful state and a key player in Indo-Asian trade. The Mughals were known for their textiles, gems, and artisanal goods, many of which reached Manila through Indian Ocean networks before being shipped across the Pacific on the Manila Galleons.

- Right: Malabar (a man from the Malabar Coast of southwest India). The Malabar region was renowned for its pepper and spice trade, which connected Indian merchants to Portuguese, Dutch, and Spanish trading posts. Malabari traders, like other South Asians, were part of Manila’s cosmopolitan merchant community, which included Gujaratis, Tamils, and Malays.

Daily Lives of Local Filipinos

This vignette provides a microcosm of 18th-century Philippine society under Spanish colonialism — with Christianized natives adopting European customs, women continuing traditional dress and livelihoods, indigenous dances persisting, and Visayans identified with martial traditions. It balances between documentation, exoticism, and colonial ethnography for its European audience.

To the left are “Indio with a lambón (cloak/garment) and India with a shawl going to church” or a Filipino Man and Woman in local dress going to church.

At the center of the image is a “India with chinina and tapis who brings guavas, a wild fruit.“ Bayabas (guava) is a tropical fruit common in the Philippines, known for its round green skin, pink or white flesh, and small edible seeds. It is widely eaten fresh, made into jams or juices, and valued for its high vitamin C content. Traditionally, its leaves have also been used in Philippine folk medicine for wound cleaning, oral health, and other healing practices.

Accompanying the woman are two children one holding a crab another cholding some sort of bamboo toy of perhaps mucical instrument.

The the rightmost is a “Visayan with a balaraw.” The balarao/balaraw is also known as a winged dagger and was a common weapon throughout pre-colonial Philippines. It’s a double-edged weapon with a hilt typically made of ivory, hardwood, or carabao horn with gold and silver adornments.

Finally, in the background are “Indios dancing the comintane.” The comintane being referred to is most likely what we know today as the Kumintang, a Filipino folk dance that is characterized by graceful, circular wrist and arm movements, often performed by women while swaying gently. This flowing motion became so iconic that “kumintang” itself sometimes refers specifically to the wrist-rotating gesture.

Right Panels

The right panel highlights maps of Guam, Intramuros (Walled portion of Manila), Zamboanga City, and Port of Cavit as well as rural sceneries of colonial Philippines.

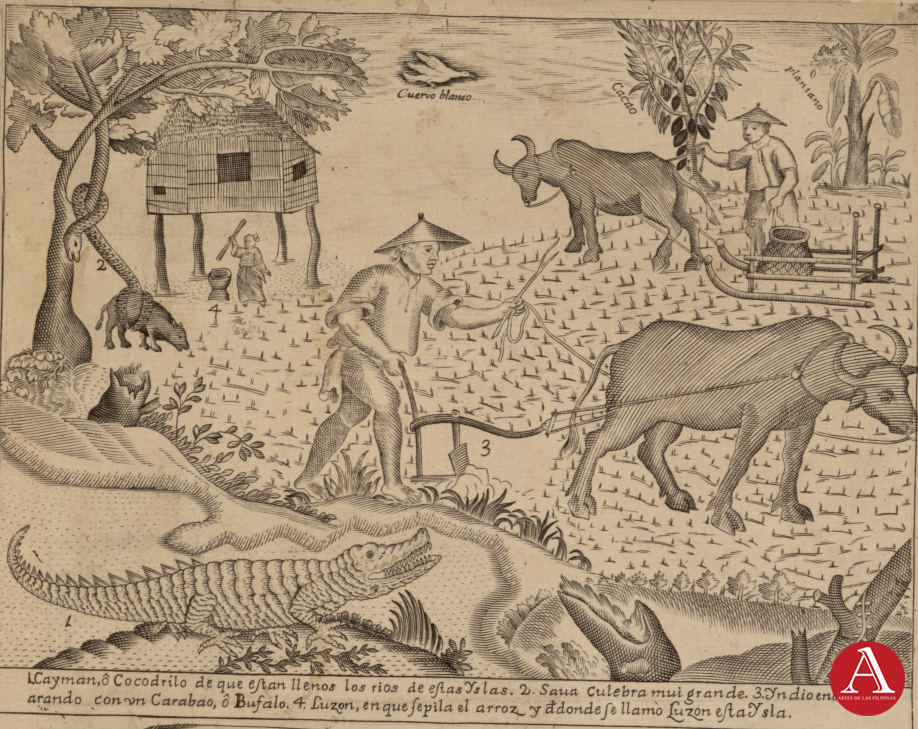

Rural Life in Luzon

This vignette illustrates the agrarian basis of life in colonial Luzon, while simultaneously emphasizing the island’s wild animals and curiosities. In the foreground and labele (1.) is a “Cayman, or crocodile, with which the rivers of these islands are filled.” This is probably a Philippine Crocodile given the potential confusion with a Cayman which is typically smaller than the Saltwater Crocodiles that are also present in the Philippines. (2.) is a “Sawa, a very large snake.” The Sawa (or reticulated python) is shown constricting a native pig.

At the center of the image (3.) is an “Indio in a field plowing with a carabao, or buffalo.” An iconic Philippine scene still very much seen in the rural areas of the country today. (4.) “Luzon, where rice is pounded, and from which this island is called Luzon.” This section in the background shows a woman pounding and dehusking rice in a lusong or a large wooden mortar, and claims the name of the island Luzon is likely derived from the mortar.

Other images in the background include a “White Crow”—perhaps an albino crow—linked to the Filipino saying “kapag puti na ang uwak” (“when the crow is white”), meaning a rare or highly unlikely event. In the upper left, a Filipino is shown harvesting “cacao”, the source of cocoa beans used to make chocolate. Although cacao is native to the Americas, it was introduced to the Philippines and the rest of Asia through the Spanish colonial trade. Beside it grows a “platano” or plantain, one of many banana varieties native to Southeast Asia. The pairing of cacao and plantain side by side highlights how Spanish colonialism drew upon both indigenous and introduced crops, transforming the islands into a productive agricultural hub.

The Island of Guam

The caption reads “The Mariana Islands, or Islands of the Thieves, stretch from 13 to 21 degrees north to south. In Guåhan is the governor and the military; only in Guåhan and Rota is there population, numbering about three thousand souls.”

Points of Interest on the Map:

- Guajan / Guåhan → Present-day Guam, largest island in the Marianas and still the most populated.

- Agaña → Present-day Hagåtña, capital of Guam.

- Umatag → Modern Humåtak, an important harbor for the Manila galleons.

- Pago → Refers to Pago Bay in central Guam.

- Merizo → Modern Malesso’, a village in southwestern guam.

- Ynarajan → Present-day Inalåhan (Inarajan), a historic village in the south.

- Orote → Orote Point or Point Udall, sGuam’s westernmost point.

The map is adorned by Spanish Galleons that often stop at southwestern Guam when coming from Acapulco, Mexico, on their way to Manila, as well as proas—the sturdy and seafaring outrigger ships common to most Austronesian people.

Intramuros, the Walled City of Manila

This vignette is an early map of Intramuros, the walled city of Manila, showing its grid-like streets, major plazas, churches, convents, and government buildings, all protected by thick stone walls and bastions along the Pasig River and Manila Bay. Surrounding the city are the districts of Binondo and El Parián, which were centers of Chinese and merchant activity. The map captures Intramuros at its height as the political, religious, and commercial heart of Spanish colonial Manila, much of which remains recognizable in today’s historic core.

- La Cathedral → Manila Cathedral (Plaza Roma / Cabildo St.)

- Palacio → Governor’s Palace (Palacio del Gobernador) (Plaza Roma)

- Rl. Aud. (Real Audiencia) → Royal Audiencia (now Palacio del Gobernador / Supreme Court site)

- Contaduría (Treasury) → Treasury Offices / Aduana area

- Almacenes → Royal Storehouses (near Fort Santiago area)

- Cap. Rl. y Cast. de Sant. → Royal Captaincy General Headquarters (adjacent to Fort Santiago, not the fort itself)

- Castillo de Santiago → Fort Santiago

- Sta. Clara → Santa Clara Monastery (near present-day Intramuros walls, demolished, now outside Bonifacio Drive)

- Hospital Real → San Juan de Dios Hospital (Hospital Real de Manila) (near Puerta Real, south Intramuros)

- Casas del Cabildo → City Hall / Ayuntamiento (Plaza Roma, now the Ayuntamiento Building)

- Col. de Sto. Tomás → Colegio de Santo Tomás (precursor to UST, formerly inside Intramuros)

- Sto. Domingo → Sto. Domingo Church & Convent (near present-day Banco Filipino, Plaza Sto. Domingo area; moved to Quezon City)

- S. Jn. de Dios → Hospital de San Juan de Dios. This was a major hospital and convent run by the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God.

- San Francisco → San Francisco Church & Convent (near today’s Manila Bulletin, Muralla St.)

- Recoletos → Recoletos Convent & Church (near present-day Mapúa University / Anda Circle side)

- La Compañía de Jesús → San Ignacio Church & Jesuit College (General Luna St., near Casa Manila / Museo de Intramuros today)

- Col. Rl. de S. Joseph (Colegio Real de San José) – San José Seminary (still exists, now in Quezon City).

- La Fundición → Royal Foundry (cannon foundry, near present-day San Francisco Gardens)

- San Agustín → San Agustín Church & Monastery – still standing and is a UNESCO Heritage Site (Gen. Luna St.)

- Sta. Isabel → Colegio de Santa Isabel (near Puerta Real Gardens today)

- Col. de S. Phelipe – Military academy → gone.

- Casa de Arzobispo → Archbishop’s Palace (Arzobispo St., now gardens / offices of Arzobispado de Manila)

- S. Potenciana → Colegio de Santa Potenciana (girls’ school) (south Intramuros, near Puerta Real)

- Beat. d S.° Dom. (Beaterio de Santo Domingo) – Community of lay Dominican sisters (precursor of Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine of Siena).

- Colegio de San Juan de Letrán → Colegio de San Juan de Letrán (still active in Intramuros today).

- Recogidas – House of Refuge for women (no longer exists).

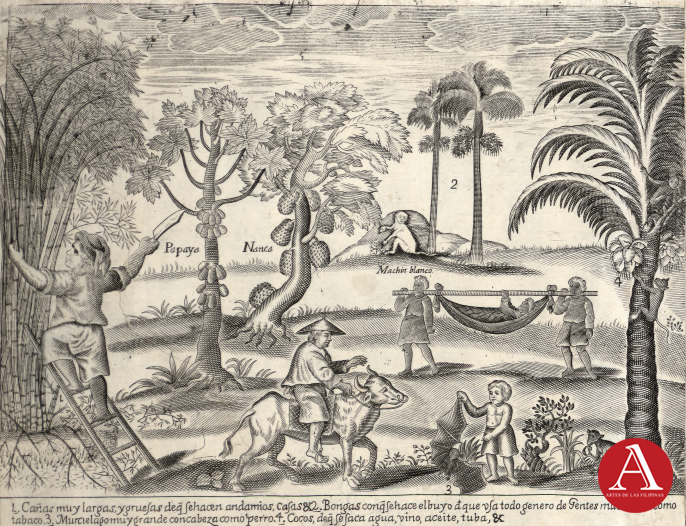

Rural Scene

This scene is both an ethnographic vignette and a catalog of the islands’ natural abundance. The foreground shows a man harvesting tall stalks of sugarcane with the aid of a ladder, while nearby trees are labeled “Papaya” and “Nanca” (Langka or jackfruit), signaling the fertility of the land. At the center, a man rides a carabao (water buffalo), a key animal in Philippine agriculture. To the right, two men carry a hammock with another figure reclining inside, and a child interacts with what is likely a flying fox under the shade of coconut palms. In the background are betel nut trees with a “Machin Blanco” or White Monkey below it.

The bottom inscription identifies and explains what is being depicted. Translated, it reads:

- Very long and thick canes, from which they make scaffolds, houses, etc.

- Betel nut, chewed with buyo (betel leaf), which all kinds of people here chew, like tobacco.

- Very large bats with heads like dogs.

- Coconuts, which here provide water, wine, oil, tuba, etc.

This panel illustrates how Spanish colonial cartographers presented the Philippines to a European audience — as a land rich in crops, useful plants, and unique customs. It frames the islands as both productive and exotic, emphasizing their economic and cultural value within the Spanish empire.

18th Century Zamboanga

This engraving depicts Zamboanga (labeled “Samboangan”), a key Spanish outpost in Mindanao. It illustrates both the fortifications and the surrounding settlement, giving a bird’s-eye view of colonial military and civilian life in the southern Philippines.

At the bottom, the numbered legend explains the key landmarks:

- Col. de la Compa. de Jhs. – College of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits).

- Casa del Gov.or – Governor’s house.

- Pozo de agua dulce – Freshwater well.

- Almacenes – Storehouses.

- Cuerpo de guardia – Guardhouse.

- Capillas – Chapels.

- Quarteles – Barracks.

- Hospital – Hospital.

- Pueblo de Lutaos – Village of the Lutaos (possibly modern day Sama-Bajau).

- El Rio – The river.

The focal point of the image is Fort Pilar (Real Fuerte de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza), the massive stone fortress constructed by the Spanish in 1635 under Governor Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera. It was intended to serve as both a military stronghold and a missionary base in Mindanao, guarding against Moro raiders and other threats from surrounding sultanates, while also facilitating Spanish expansion and Christianization efforts.

Inside the walls, the Jesuit college (1), governor’s house (2), chapels (6), and barracks (7) demonstrate the blend of religious, administrative, and military power concentrated within the fort. Outside the walls, the Pueblo de Lutaos (9) shows the settlement of native allies who were crucial intermediaries between the Spanish and the Muslim populations of Mindanao. The depiction of ships offshore underscores Zamboanga’s importance as a naval base securing the southern seas.

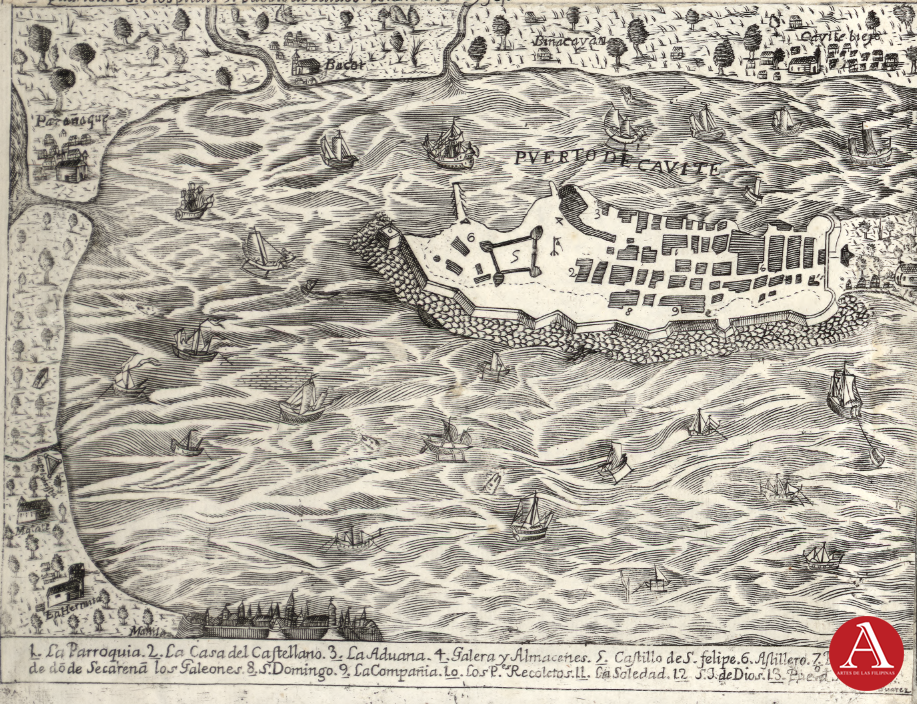

Puerto de Cavite

This panel shows Puerto de Cavite (the walled port-city of Cavite, Philippines), which served as the main shipyard and naval base of the Spanish during the Manila–Acapulco Galleon trade. The engraving is oriented with south positioned toward the top.

At the bottom of the map there’s a numbered caption/legend:

- La Parroquia – The Parish

- La Casa del Castellano – The Castellan’s House (commander’s residence)

- La Aduana – The Customs House

- Galera y Almacenes – The Galley and Warehouses

- Castillo de S. Felipe – Fort of San Felipe

- Astillero – The Shipyard

- Puerto de donde se sacaran los Galeones – The Port from where the Galleons are launched

- S. Domingo – (Church/Convent of) Saint Dominic

- La Compañía – (Church/Convent of) the Jesuit Company

- Los R. Recoletos – The Augustinian Recollects

- La Soledad – (Church/Convent of) Our Lady of Solitude

- J. J. de Dios – The Hospital of Saint John of God

- S. Joaquin – (Church/Convent of) Saint Joachim

This engraving of Puerto de Cavite not only highlights the fortified port city but also situates it within its surrounding settlements. Across the top and sides of the map, several towns and barrios are labeled, providing a glimpse of the Manila Bay coastline in the 17th–18th century. To the left, near the coast, are Ermita and Malate, both early Manila districts known for their churches and seaside communities. To the bottom of the map is the walled city of Intramuros. Just above Cavite, inland towns like Bacoor, Binacayan, and Cavite Viejo (now Kawit) are shown, important settlements that supported the port with resources and manpower.

Further along the shore appear Parañaque and La Monina (Sta. Monica), both of which were centers of fishing and farming that supplied Manila and Cavite. These references show how Puerto de Cavite was not an isolated military outpost but rather the centerpiece of a dense network of towns along Manila Bay. The map captures both the strategic role of Cavite as Spain’s naval base and the everyday connections with nearby communities that sustained the galleon trade and the colonial capital.

Legacy and Heritage Value of the Murillo Velarde Map

The Murillo Velarde map has endured as one of the most significant cartographic artifacts in Philippine history, not only for its scientific accuracy but also for its cultural depth. Its technical precision established a standard reference for subsequent European and Asian maps of the archipelago well into the nineteenth century, influencing how the Philippines was represented in global geography. The inclusion of detailed coastal outlines, ports, and navigational routes meant that the map served practical purposes for maritime travel and administration, while its enduring accuracy reinforced its authority as a geographic baseline.

Equally important are its ethnographic illustrations, which capture a visual record of the peoples and social diversity of the eighteenth-century Philippines. These vignettes, depicting various ethnolinguistic groups, settlers of mixed ancestry, and local communities, preserve images of everyday life and identity that might otherwise have been lost. In this sense, the map transcends its utilitarian function as a navigational chart; it also serves as a cultural document, recording the human and social realities of the archipelago under colonial rule.

As a heritage artifact, the map is frequently described as the “mother of all Philippine maps.” This designation reflects both its pioneering status as the first scientific chart of the Philippines and its symbolic role in shaping national historical consciousness. The map’s survival, reproduction, and display in academic and museum contexts underscore its importance as part of the country’s documentary heritage. Its presence in exhibitions and scholarly studies reinforces a sense of cultural continuity, linking present generations with the eighteenth-century experiences of mapping, knowledge-making, and identity formation.

For historians, the map offers an indispensable source for the study of colonial-era spatial knowledge and representation. For heritage institutions, it embodies a symbol of identity and resilience, reminding audiences of the Philippines’ complex past as a space of encounter between global empires and local communities. In bridging these roles, the Murillo Velarde map occupies a unique position as both a scientific achievement and a cultural treasure, ensuring its lasting legacy in Philippine historical memory.

References

Murillo Velarde Map – Home. https://murillovelardemap.com/

Philippine Consulate General – Chicago. “Press Release.” https://www.chicagopcg.com/pressrelease-details-47.html

Ateneo Global. “‘Mother of Philippine Maps’ Settles Sea Dispute with China.” https://global.ateneo.edu/news-events/2015/%E2%80%98mother-philippine-maps%E2%80%99-settles-sea-dispute-china

Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. “Mapa de Las Yslas Philipinas Hecho Por el Pe. Pedro Murillo Velarde de Compa. de Jesus.” https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/yslasphilipinas-murillobagay-1744

Library of Congress. “A Hydrographical and Chorographical Chart of the Philippine Islands.” https://www.loc.gov/item/2021668467/