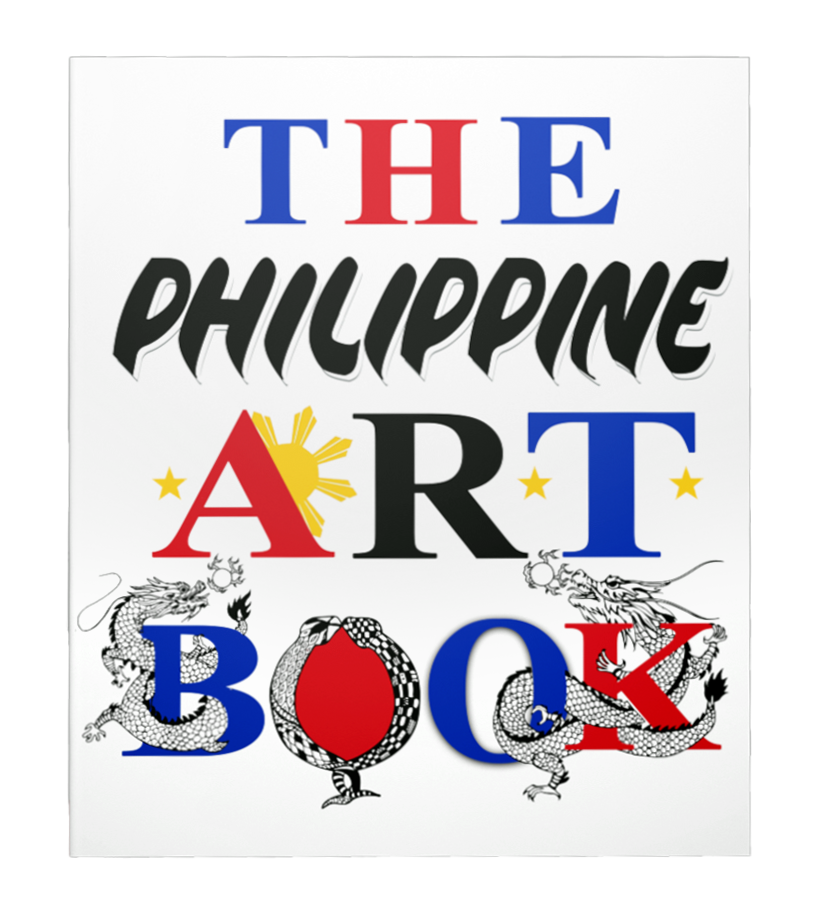

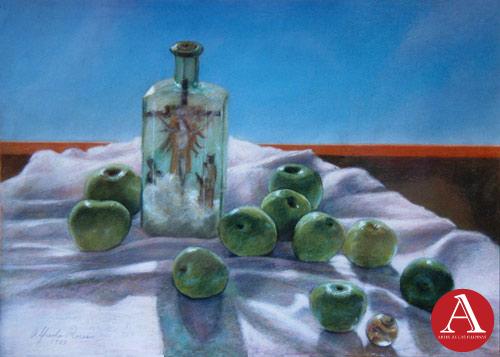

Fraser Island, Still Life

Alfredo Roces: Man of Arts and Letters

(First of Two Parts)

by: Christiane L. de la Paz

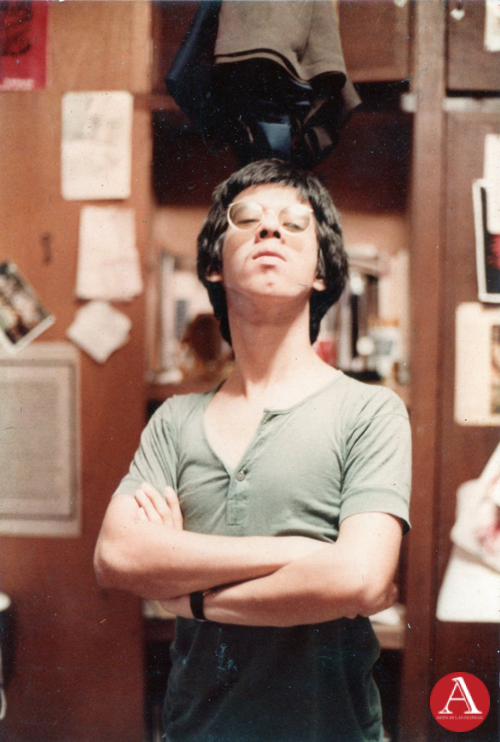

January 2016--Alfredo Roces holds a prominent place in the history of Philippine art. He is a painter who started with a figurative style but soon began to amalgamate Expressionism, Fauvism and Impressionism in his paintings. As he move into Abstract Expressionism and assemblage, he also branched out in these various separate directions without abandoning the figurative and realist schools. More than that, he is also a notable author of Philippine art books whose ability to connect with the readers comes down to how he brings out the fullness of his subject. His books, Amorsolo 1892-1972, Filipino nude: the human figure in Philippine art and a portfolio of nudes, Legaspi The Making of a National Artist, Anita Magsaysay-Ho In Praise of Women, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo & The Generation of 1872, to name a few, immortalized his writing style. Clear and solid sentences, apt words and sentences to reflect the truth about his subject are the distinguishing marks of his style. He is a recipient of the Ten Outstanding Young Men in Humanities and a Hall of Fame awardee at the Filipino Australian Artists and Cultural Endeavor Society, among many others.In this two-part interview with Roces, he takes us back to his early years as a student of Dominador Castañeda and then George Grosz, his involvement in the formation of the Saturday Group, his artworks during martial law and his life and activities in Sydney, Australia.

How did you start your career as a painter?

During World War II, when I was about 10 years old, I made a copy of Mickey Mouse on plywood, about four inches high in size, cut that out and painted it with my father's discarded pastel sticks which I pulverized and mixed with water. I thought it would be permanent and mounted it on a small, flat wooden stand. My sister-in-law was so delighted with it she paid me 40 centavos Japanese time money. My first art sale.

But of course one really starts any career by formally learning the craft and I started with weekly private tutoring under UP Prof. Dominador Castañeda in 1947. I was 14 years old and a first year high school student then. I then completed four years including summers of fine arts course at the Notre Dame University in Indiana, USA (1950-1954), after which I took an extra year of drawing at the Arts Students League of New York under the Dada German painter, George Grosz (1955-1956). I therefore started my career by going through eight long years of formal academic training.

Can you still recall the first image that you painted?

I must have always been drawing as child because my father got Castañeda as my private tutor without my mentioning to him anything about studying art. Since none of my elder eight brothers had ever been provided with an art tutor, he must have observed my unusual interest in art.

My first oil painting under Castañeda was a still life, probably 1947-8. My first oil self-portrait still under Castañeda is dated 1950.

First oil painting under Dominador Castañeda (1948)

Why did your father handpick Castañeda to tutor you?

My father's first choice was Fernando Amorsolo but he had retired from UP to concentrate on painting. Amorsolo recommended Castañeda who had replaced him as head of the fine arts at UP. Castañeda had studied in Mexico in the days of Siqueros and Orozco.

What did you learn from your study under him?

Castañeda was an excellent teacher, gentle, patient and informed about technique. I learned one-on-one from him, drawing, proportion, chiaroscuro, perspective, anatomy and the characteristics of colors and the use of pastel, watercolor and oil. He was practical rather than theoretical and he built into me the need to personally care for one's painting gear and equipment and how to wash brushes after using.

He also showed me a book, Constructive Anatomy by George Bridgman a copy of which he had drawn and copied page by page. He was a dedicated artist and teacher. We enjoyed a healthy rapport. When I returned from my studies in the US, he asked me to write the introduction for his book, Art in the Philippines (1964).

Painting under Castañeda, portrait of his sister-in-law, Lita, the wife of his brother Joaquin, Congressman for Manila

Did you have to go to his house in La Huerta, Parañaque or did you hold your weekly lesson in your house or at the UP SFA?

Castañeda would come to our house in Pasay. On occasion he brought his little son Porfirio along. Porfirio remains a friend.

Why did your father choose you to study art among your eight other siblings?

I never mentioned taking art studies to him. He must have observed my interest in the arts. Depending on individual interests, my other siblings got different special tutoring such as guitar and piano for the musically inclined.

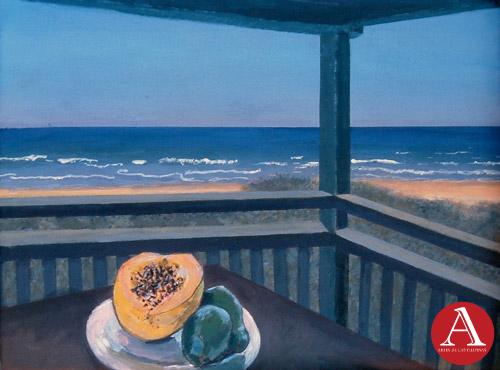

With his brother Marcos at the Notre Dame University (circa 1951-1952)

How long did you study under him?

I started around 1947, every Saturday afternoon. I stopped only when I had graduated from high school and left for the US in 1950. So three years.

You were the only one who became an artist. What are the interests of your other siblings?

Three brothers, Rafael Jr., Joaquin and Alejandro were established writers, writing daily columns for newspapers, Tribune, Manila Times, etc.. Alejandro who wrote short stories was named National Artist for Literature. Two were in politics: Joaquin who served as Congressman for Manila's 4th district for four terms. Jesus was Vice Mayor of Manila when Arsenio Lacson was the mayor. The others were businessmen.

Mirror, third prize winner at the Notre Dame University Art Competition (1953)

What made you decide to study Fine Arts at the University of Notre Dame?

My father's family choice. It was a reputable Catholic University which offered a rounded academic education. In the 1930s, my two eldest brothers had also studied there. I went with another sibling, Marcos who took up commerce there. He was a year ahead of me. I started as a general bachelor of arts student but when I won a silver star for a watercolor I had submitted in a student competition in my first year there, I was encouraged to major in Fine Arts. My minor was Philosophy.

The Philosophy was for a Pre-Law course?

No. It was for a general course for Bachelor of Arts. My major was Fine Arts but one had to minor in an academic course. It was an academic college degree and not a technical degree.

What career were you planning to pursue after college?

I had in mind that in a general sense a BA would qualify me for general executive employment but of course I expected to do commercial art work perhaps advertising and of course some writing.

You also took another year studying drawing at the Arts Students League of New York. Were you after having George Grosz as your teacher?

I was first of all eager to study at the ASL because I wanted to strengthen the basic art skill of drawing and when I saw George Grosz whose satirical and expressive line work I admired was one of the teachers so I opted for his class.

Art class at Notre Dame University (1950-1954)

What was his class like?

He would go over the work of the students as we drew the figure with a model before us. He gave individual attention to each of us. He made us use a fat bamboo reed sliced diagonally at the end and India ink. This medium forces you to be decisive as there is no room for error. It taught you to observe, analyze and then attack the paper. His lines were not neat and precise. They were alive and expressive.

How was George Grosz as a teacher?

He was conscientious. Once he saw a figure drawing I was working on and he explained to me the inner anatomy of the throat, drawing the Adam’s apple and tendons on the blank portion of my drawing to demonstrate that even if these are not visible, your drawing and your lines must imply these. I would bring my paintings in progress to show him and even if this was not part of his class subject of drawing, he would comment and give me pointers. Once he brought the work of Grunewald the following session to show me just what he meant the previous session regarding a painting I had brought to show him. I have an autographed copy of his book with a sketch dedicated to me. Our studio-classrooms were at the ASL in the heart of the city on West 57th street. We would show up in the morning and he would be there.

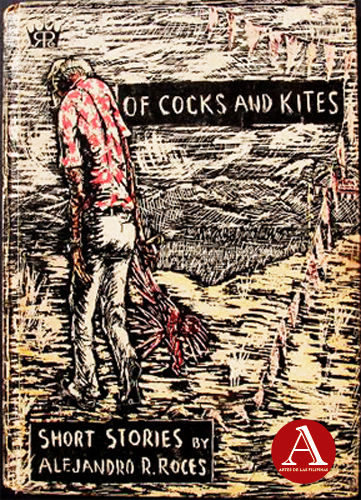

Cover design of Cocks and Kites (1957)

From the year you began painting professionally in 1957, has your career been divided in phases?

I began about 1957 by illustrating my brother Alejandro’s book of short stories “Of Cocks and Kites by Regal Publishing, 1959. I started with a figurative style but soon began to amalgamate impressionism, expressionism and fauvism in my paintings, even when I was at Notre Dame. Very quickly I began to explore abstract expressionism and assemblage, branching out in these various separate directions without ever abandoning the figurative and realist schools. Critics’ reviews of my first show noted these “confusing” diversity and subsequent critics in subsequent shows made the same observation. So I probably work in phases, but you might say I journey simultaneously in diverse directions through diverse media and forms of expressions in a continuous progression of paintings, assemblage, writings books, photographs, pottery, digital art, earth art, and whatever new technical and artistic challenges come my way.

But another way to look at phases is through my own phases in life. I went through a long student phase (1947-1956), followed by an effort to get established as an artist and then as a practicing artist while holding down various jobs such as lecturer in Humanities at FEU, Daily Columnist Manila Times and CEO Massprom, etc. up to Martial Law (1958-72) and my migration to Australia (1977-2015) which of course forced me to be an artist in both countries with a stronger inclination to be part of the Philippine art scene.

Sonatina (1958)

What were you doing during the martial law?

During the Martial Law I continued to paint especially because I could no longer write a daily column for the Manila Times which had been closed down. I was active with the Saturday Group. I even had a drawing retrospective at the Cultural Center of the Philippines Small Gallery in 1974. But more than anything, I was occupied as editor in chief of Filipino Heritage. This project was opposed by Marcos who wanted to hi-jack it for his own political purposes. This conflict pushed me out of the Philippines to complete the project in Australia.

What was the landscape of Philippine art at that time?

It remained fairly active. Imelda Marcos, as you know, portrayed herself as the goddess of the arts. Marcos too had his own coterie as exemplified by Malang. Given that the art institutions were all Marcos fronts, you only have to look at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, the art section which was under Chabet and Albano and the 13 Artists Award they controlled. The Metropolitan was run by Arturo Luz and so too the Design Center of the CCP and also the MOPA. The favored architect was Lindy Locsin. But of course life went on for artists who were not openly anti-Marcos or Communist. The Saturday Group for example remained active but kept away from controversial politics. Some Marcos artists were members of the Saturday Group. However, art patronage was the domain of Imelda and her Blue Ladies. Rustan's Gallery Bleue, for example, was a thriving gallery then. The same with getting favorable reviews and exposures in the Marcos controlled media, you had to be simpatico to them.

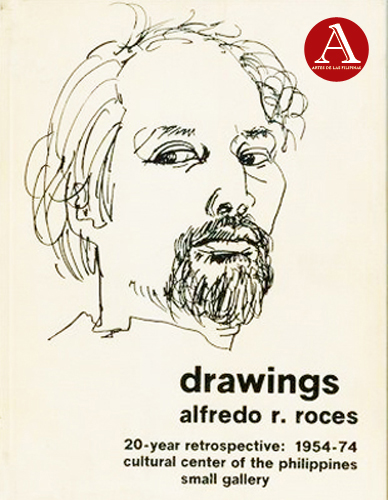

Cover booklet of his 20-year retrospective of drawings at the Cultural Center of the Philippines

What were you painting in those days?

I continued to paint nudes, still-life and landscapes with the Saturday Group. I was getting more into assemblage. Exhibitions went on as normal. In fact, because Imelda Marcos patronized the arts, there was much activity and generous patronage for favored artists. When Albano invited me to put up a show at the Small Gallery of the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 1974, I chose to present a 20 year retrospective show entirely of drawings. I sneaked in a political comment about Martial Law that happily escaped everyone's notice --Caged Drawing and Bottled Drawing. But at least I had covertly recorded my sentiments.

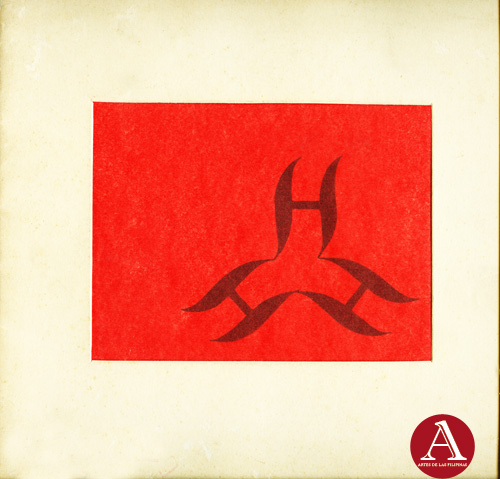

CCP logo designed by Alfredo Roces

Let's talk about the CCP logo that you designed. What was the idea behind it?

When I worked on this logo, I had researched a speech of Mrs.Imelda Marcos, the founder of CCP in which she defined the arts as "the good, the true and the beautiful." In Filipino these would be "Kabaitan, katotohanan at kagandahan". Immediately the Katipunan's KKK came to my mind so I used the original script "K" in Bonifacio's Katipunan flag and arranged three K's in a dynamic triangle. Truth, Beauty, Goodness, —the attributes of arts and culture and thus of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. This is in direct link with our nationalist heritage seen in the ancient Tagalog script and the Katipunan logo, given life in contemporary abstract form.

Was it you who founded the Saturday Group?

Yes I was one of the main founders but the group is not one person's creation, a core had to start it. The original others were HR Ocampo, Atty.Tony Quintos, Enrique Velasco, followed by Cesar Legaspi, Tiny Nuyda and Bencab. A small slim booklet entitled 10 years of Saturdays was published by the group in 1978 documenting this.

Tony Quintos and I were having lunch at the Taza de Oro when we chanced upon Nanding Ocampo there.We decided to meet again the following Saturday. The group grew slowly from there. Nanding had just retired from work at Philprom. His companion Cesar Legaspi also retired so he joined us. Each one spread the word and brought art-oriented friends like Enrique Velasco. No rules and no official formal members. You come and go as you please. No officers and no elections. This kept the group cohesive but very loose and flexible. When I moved to Australia and Nanding Ocampo and Legaspi passed away, the group decided to hold elections changing its character.

With AAP President, Purita Kalaw Ledesma, during his one-man show in 1968

His brother Alejandro at his first one-man show. He later served as the Secretary of Education under Macapagal and later was named National Artist for Literature.

Please tell some details of your first exhibition.

I showed sixty-seven works of oil and watercolor paintings, mixed media and drawings. That was on March 19, 1960 at the Contemporary Arts Gallery, owned and run by Manuel Rodriguez Sr. on 1416 A. Mabini, Ermita. This exhibit was featured as a Cover story in the Sunday Times Magazine, April 24, 1960.

Shoe from his solo exhibition, Memory is Short, Cultural Center of the Philippines (1960)

Why in his gallery?

I knew Maneng Rodriguez personally and I liked the coziness of his gallery. At that time the Philippine Art Gallery was in decline for lack of professional management as Lyd Arguilla was out of the country and some artists warned me about paintings not being well cared for there. Luz Gallery did not exist then.

Did the Luz Gallery do a better job in caring for the artists’ works?

Luz Gallery was more professional but I felt it catered too much to a social elite such as Imelda Marcos and her Blue Ladies. Luz did a good job of caring for his artists, however. I never had a solo at Luz but when I next exhibited, I chose the newly opened Solidaridad Galleries of a writer friend Frankie Jose because like me he was a bit of a rebel against the establishment.

How was it like exhibiting during the 1960s?

The artist was left very much on his own to handle his own show including the hanging, cataloguing, sending of invitations, the refreshments and the publicity. It was very much a loose, informal system not like the professional galleries of today.

Recollection of Paradise, pastel on paper, Eddie Pineda Private Collection

Would you have wished that it could somehow be formal that maybe the gallery could facilitate the launch?

There was a need for professionalism in art galleries and among some artists and art critics. I wish the gallery owners would handle not just the launch and the publicity but also the sales clientele and the briefing of critics and media people.

Did you even make an effort in addressing your critics about your works being confusing?

No, I left the critics to make their comments then. Then as now, I think the artist should show his public what he can do, versatility being an asset; but it seems the critic and the public and the collectors expect one theme, one manner of expression. In the same manner, it is regarded as a virtue to be self-taught rather that to recognize an artist's period of study and years of training under established schools or artists.

But there was one instance when a critic, Ray Albano, wrote about an exhibit of mine and I disagreed about his views so strongly I answered him in print in the same magazine. It was a scholarly debate not a personal squabble. It’s a long story which I could recount if you wish.

We didn’t have a lot of art critics then and now. Why do you think this has been the case?

Yes, I think that is one weak area but now that I have experienced the Australian art scene, it is not unique to the Philippines.

What do you expect a critic to do?

A critic would best serve as the bridge between the artwork and the viewer. Empathy with the artist would be vital but some assume the stance of the devil's advocate. I expect a critic to create interest and understanding for art in general and for the artwork and artist he/she is discussing. Just like a good friend will tell you when you are out of line, a critic should also be candid.

You were also reaping awards at the Art Association of the Philippines. Was it a big deal to join and win in art competitions?

There were few opportunities to gain recognition and the Art Association of the Philippines was one of the few who acknowledged artists and their work, so to me it was a big deal. But such awards were only effective if one were consistently a winner and if one knew how to capitalize on it.

What happens to the artist when he wins an award?

From my own personal experience, awards do not automatically open any magic doors nor increase sales nor change the established opinions of critics and some fellow artists who champion their own school of artists. At most, it gives one a bit of a shield against the negative attacks of the nay-sayers. It gives you some confidence that what you are doing is worthwhile.

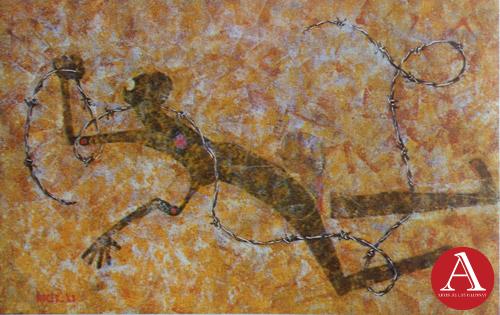

Man Dying, mixed media

In terms of looking at your body of work, how do we know that a painting is by Alfredo Roces?

I prefer to leave that to viewers, art historians and critics. From my very first show the critics have expressed confusion over my diversity. It is my diversity and versatility that defines me. For my part, I have absolutely no desire to “stylize” myself. I rebel against the art establishment’s pressure to package my art works like a commodity, ala McDonald’s or Coca Cola, for purposes of brand recall, just to please the critics and the art collectors. The problem of labelling, cataloguing, classifying into schools of art, and so on, belongs to the art historian and art critic, not to the artist.

You began your assemblages in 1968.

It started from my third one-man show held at Solidaridad Galleries in 1968. I used found objects meant to evoke some personal feelings and memories from the viewer. Not necessarily identical to that of the artist. This work may contain a serious comment or it could be simply by play or perhaps a bit of both. One writer, Sylvia Mayuga of Solidarity, January 1969 saw this specific piece as poking fun at “culture vultures.” But it is not pure play and satire, it is also meant to look at actual, authentic mementoes of the past, to stir the viewer’s feelings and ideas when confronted by these now discarded precious art objects of our past rearranged in a different format. In this work are actual 15th century Ming shards, prehistoric earthenware spindle whorls and an old santo, but there is also the contemporary crushed salmon can, and the modern abstract expressionist painting. So it is my turn to ask the viewer: what do you think?

Did you get any feedback from viewers?

Not for that particular piece that I remember. It is difficult to get serious reaction and reflection from my assemblage as the initial response is that I am pulling the viewer's legs.

To Liberate Mendiola Bridge (1970)

In 1972, you represented the country at the Paris Sud International Art Show. What did you enter?

Those in charge of the Philippine participation instructed me to submit only a very small work that could be hand carried in an airline flight. So I gave them a very small three-piece assemblage of objects buried in polymer, similar to the one that won an AAP Grand Prize in 1972 but with a different subject content. Frankly, I don’t recall the title nor what happened to that trio-piece.

Receiving the Pamana Award from President Aquino at the Malacañang Palace (2014)

What other art awards did you receive?

Pamana ng Pilipino Presidential awards for Filipino individuals and organizations overseas from Commission on Overseas Filipinos: 2014

Hall of Fame, lifetime achievement award, FAACES (Filipino Australian Artists and Cultural Endeavor Society) Sydney, 2011

Green & Gold Artist: Centennial of Nicanor Reyes Sr., Far Eastern University, 1994

Artist of the Year: Art Association of the Philippines (AAP): 1975

Grand Prize, 25th Annual Show, AAP: 1972

Philippine representative, Paris Sud; France,1972

Honorable Mention: Graphic Division, AAP,1961

Third Prize, Students Art Show, University of Notre Dame, 1954

Silver Star, Students Art show, University of Notre Dame, 1950

Harvard International Seminar (under Dr. Henry Kissinger) Grant, 1965

Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) in Humanities

Are you known for any series?

I exhibited a series on martial law at the Cultural Center of the Philippines entitled “Memory is Short”. But by “series” I assume you mean painting a given subject continuously in an explicitly given form or “style”. No, I do the opposite. I take a given subject and come up with a variety of ways and mediums to give this expression.

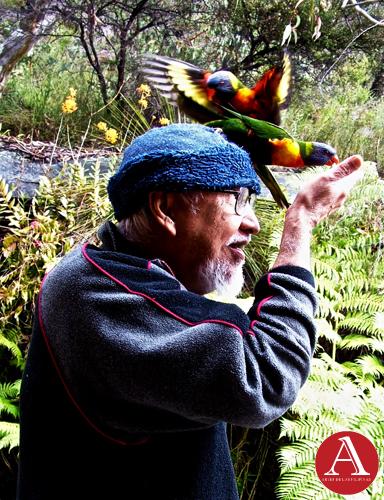

Photo taken by his wife, Irene in their backyard with colorful parrots

What made you decide to migrate to Sydney?

With the imposition of Martial Law I could no longer write freely. The art world became stifling with artists favored by Madame in their glory and those marked as non-conformists put down. For example, my passport was withheld. I was not given an exit permit and could not travel overseas even when I had received grants from reputable institutions such as Yale and a Buddhist temple in Thailand to name a few. I wanted a better atmosphere for my growing children.

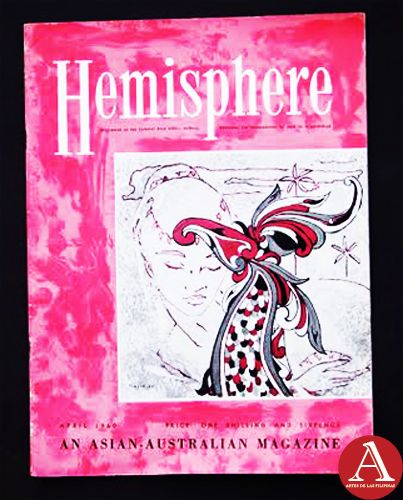

Cover design of a Sarimanok for Hemisphere Magazine/ Australia/ (1960)

Yes, but why Australia?

I was working on Filipino Heritage at the time. The publishers, The Hamlyn Group, were an Australian company so when Marcos opposed the project, I had to go to Australia to finish production from there to prevent Marcos from tampering with the text. It was an opportunity to gain resident status and bring my family with me. I thought I would try it for a year or two.

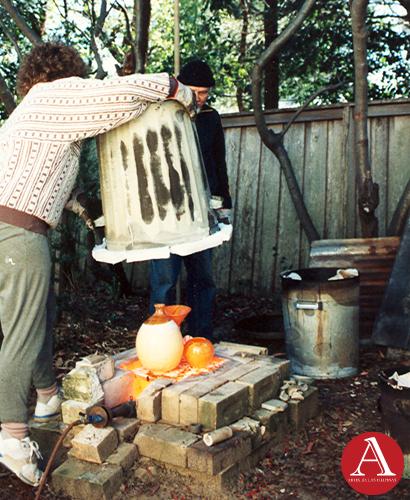

Raku Firing, Sydney

When you migrated to Sydney in 1977, you branched out into pottery, did you attend a school or workshops for this?

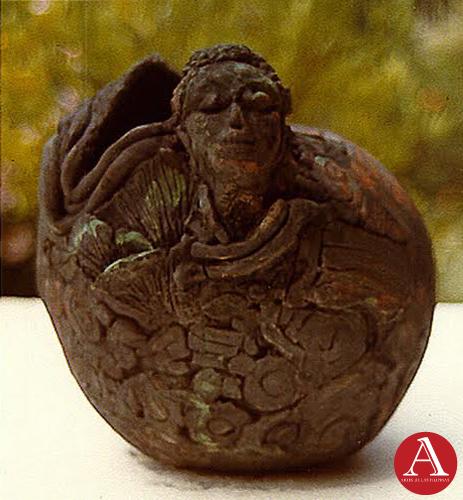

I attended workshops in the 1980s at the Community Art Center in Belrose, Sydney where I studied both kiln fired ceramics and raku fired clay. But I do not own a kiln and so was forced to give up pottery when the community center closed. My interest in pottery goes back to World War II when we had to dig a temporary air raid shelters in our garden and as a boy discovered clay. I knew nothing about firing, but I loved making clay figures and drying the works in the sun. As an art student at Notre Dame, I was taught sculpture using plasticine which we then cast in plaster. I had an exhibit at the Kamalig Gallery of my pots, 1980 and 1982, and another of my sculptural figures at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

Earthartwork at Terrigald Gosford, New South Wales

Sarimanok by Alfredo Roces and Rainbow Serpent by Kevin Duncan

Have you ever exhibited your pottery or other works in Sydney?

I have exhibited at the Watercolor Institute and other group shows. I had a one man show at the Philippine Consulate. Recently with three other Filipinos artists we exhibited at the Arthouse in downtown Sydney.

Pottery work (1982)

To be continued...

Recent Articles

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISM

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISMJUNE 2024 – Federico Sievert was known for his art steeped in social commentary. This concern runs through a body of work that depicts with dignity the burdens of society to...

.png) FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO

FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISOMarch 2024 - Alexander Narciso is a Philosophy graduate from the Ateneo de Manila University, a master’s degree holder in Industry Economics from the Center for Research and...

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim HigginsSeptember 2022 – The fashion exhibition of Salvacion Lim Higgins hogged the headline once again when a part of her body of work was presented to the general public. The display...

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All TimeOne of the emblematic komiks writers in the Philippines, Jose Zabala Santos contributed to the success of the Golden Age of Philippine Komiks alongside his friends...

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

The Philippine Art Book (First of Two Volumes) - Book Release April 2022 -- Artes de las Filipinas welcomed the year 2022 with its latest publication, The Philippine Art Book, a two-volume sourcebook of Filipino artists. The...

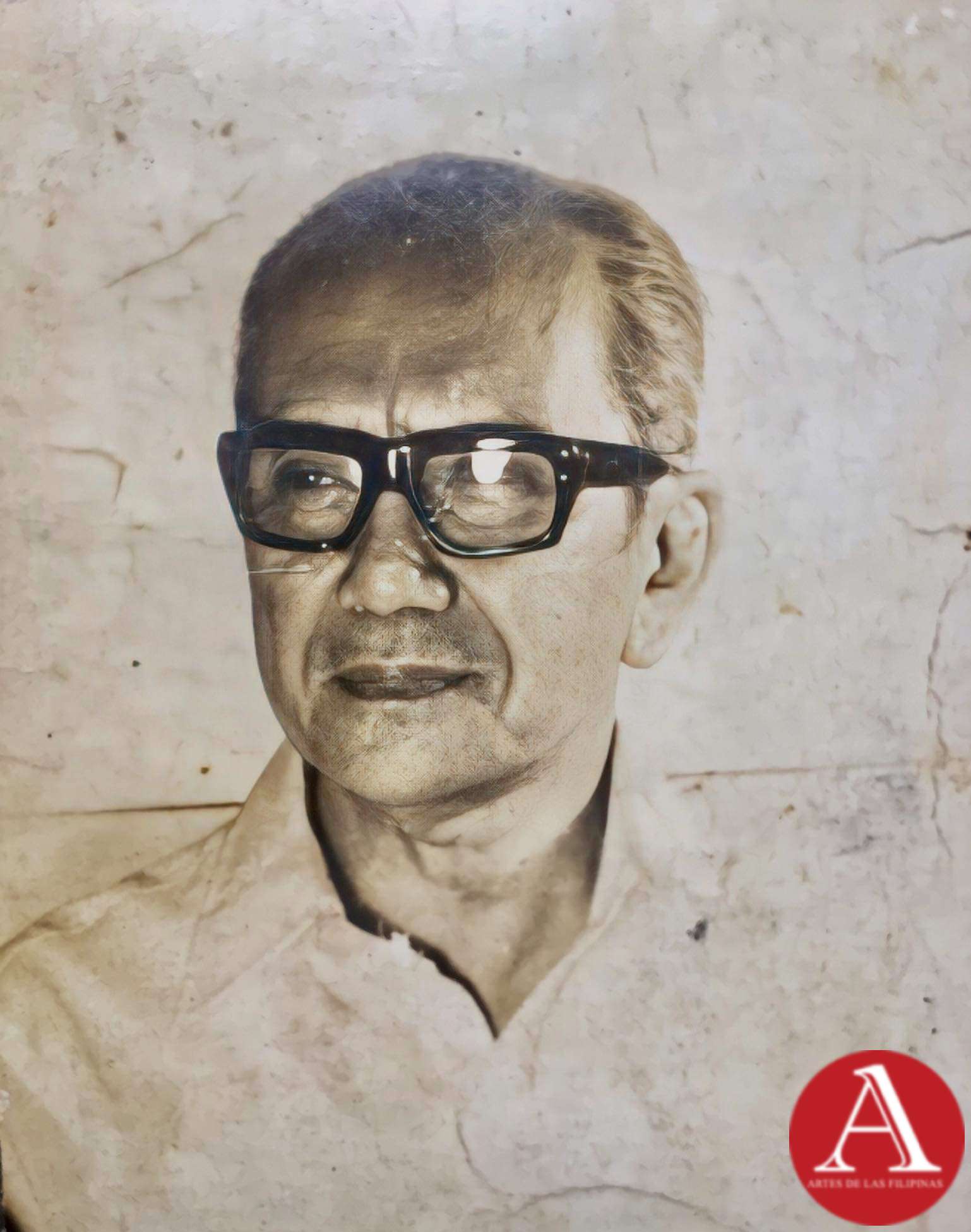

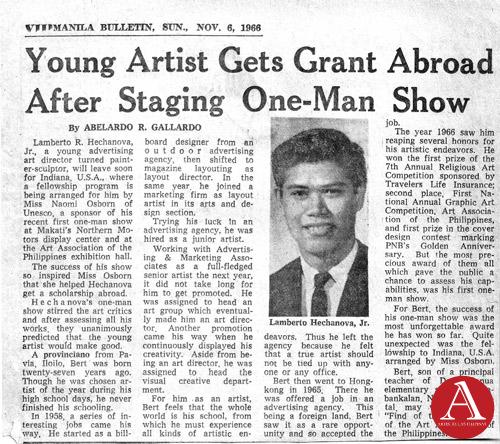

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and FoundJune 2018-- A flurry of renewed interest was directed towards the works of Lamberto Hechanova who was reputed as an incubator of modernist painting and sculpture in the 1960s. His...

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise CemeteryApril-May 2018--The Pere Lachaise Cemetery in the 20th arrondissement in Paris, France was opened on May 21, 1804 and was named after Père François de la Chaise (1624...

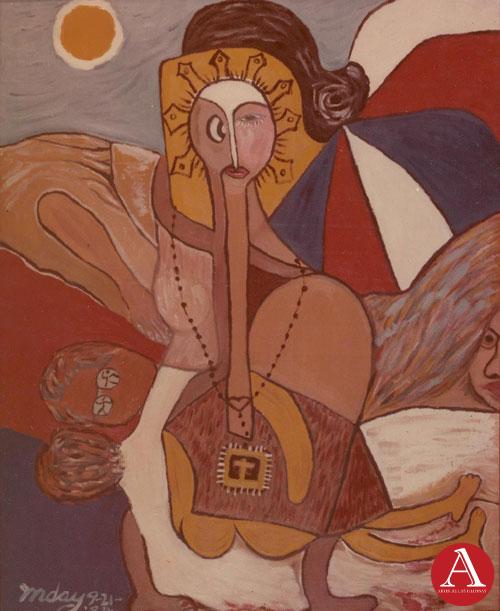

Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday

Inday Cadapan: The Modern IndayOctober-November-December 2017--In 1979, Inday Cadapan was forty years old when she set out to find a visual structure that would allow her to voice out her opinion against poverty...

Dex Fernandez As He Likes It

Dex Fernandez As He Likes ItAugust-September 2017 -- Dex Fernandez began his art career in 2007, painting a repertoire of phantasmagoric images inhabited by angry mountains, robots with a diminutive sidekick,...