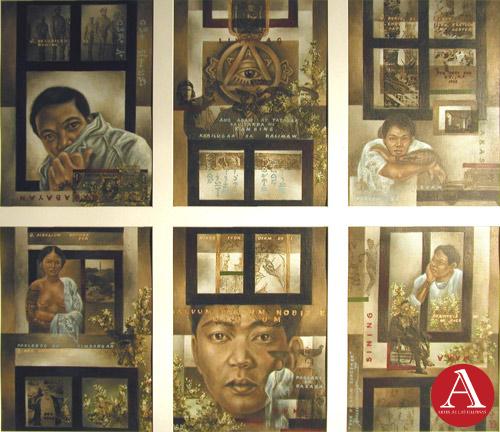

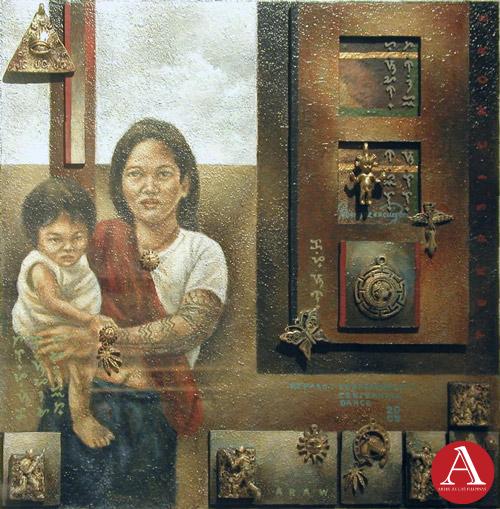

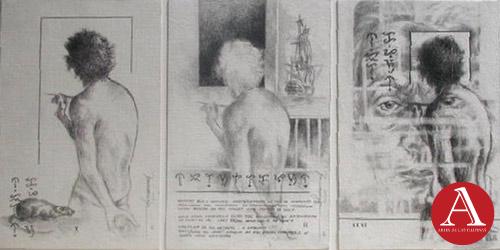

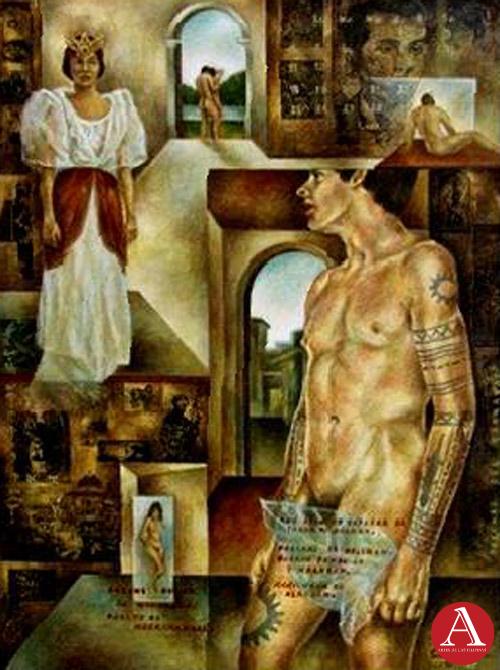

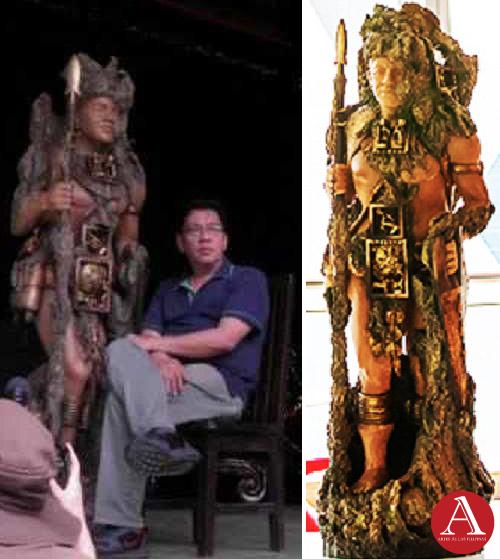

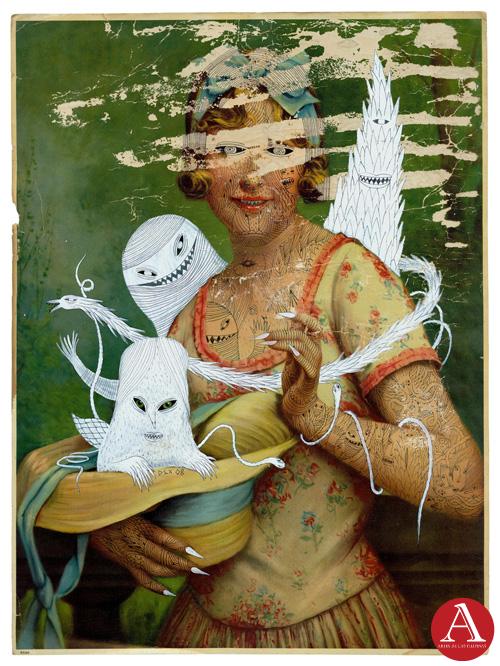

Repaso ng Tres Personas, Imagining Identity,100 Self-Portraits by Filipino Artist Exhibtion, Finale Art File (2011)

Noel Soler Cuizon’s Gesamtkunstwerk and Everything in Between

by: Christiane L. de la Paz

April-May 2017—The public exhibition of Noel Soler Cuizon’s works began in 1987 when he was a member of Hulo, a group of alumni students of the Philippine Women’s University who explored non-traditional Western materials. Freeing the hand from the brush and utilizing it in other manual aspects of works led him to work with wood assemblages which he composed in a structure of multi-frames that overlapped each other and accompanied with painted cut-out figures, thus, engaging the viewers to interact with the contents of his art pieces. His works were later referred to as interactive wood assemblages. In 2004, he began exploring performance art as a medium to expand on the interactive model of his early works as well as to define the symbiotic relationship between the message and motivation of all his other works. Markadong Bayani (2004) was his first public engagement with performance art in Manila which he mounted at the Kanlungan ng Sining in Rizal Park. Reenacting the execution of Jose Rizal infront of his monument, he and Crisanto de Leon, his collaborator, appropriated the idea of Christ falling three times when he carried his cross. In this interview, Cuizon has done a sensitive job of taking the readers to the impulsion of his artistic hunt beginning with his maternal grandmother, Natividad Fajardo and his aunt, Brenda Fajardo. He also provided some very welcome and interesting anecdotes on his art professors in the Philippine Women’s University, his undergraduate thesis, his early years as an exhibiting artist at Hiraya Gallery, his teaching career and how all these nascent experiences translated into his art. He also passed on some of his views about how his assemblages should be regarded, the relevance of curatorial reviews, the frills and thrills of an artist, among several others, striking a balance between too much and too little editorial intervention. One is led to believe that his art practice typifies the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork).

What projects did you engage in after graduating from the Philippine Women’s University in 1987?

I went full-time as a freelance artist/painter for the most part. I also worked on various projects with some Theater Productions. In PETA, I was part of NGO, Ang Dagang Patay by Nonoy Marcelo and the re-staging of Aurelio Tolentino’s Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas. At the Cultural Center of the Philippines, I was involved with the Kwentong Lukayo and at the PASILAG, the restaging of Kwentong Lukayo and Sumpa ng Diwata. I joined their Set and Costume Design Teams. Occasionally, I held informal drawing and painting workshops through the outreach programs of several cultural groups. I was invited by Ayala Museum to start with its Escuela Sa Museo program in 1995. I stayed with the institution until 1998. I also put up a catering business with cousins and friends that provided artists and art centers a different approach to artists’ receptions. We would do thematic cocktails for exhibition openings and other art events.

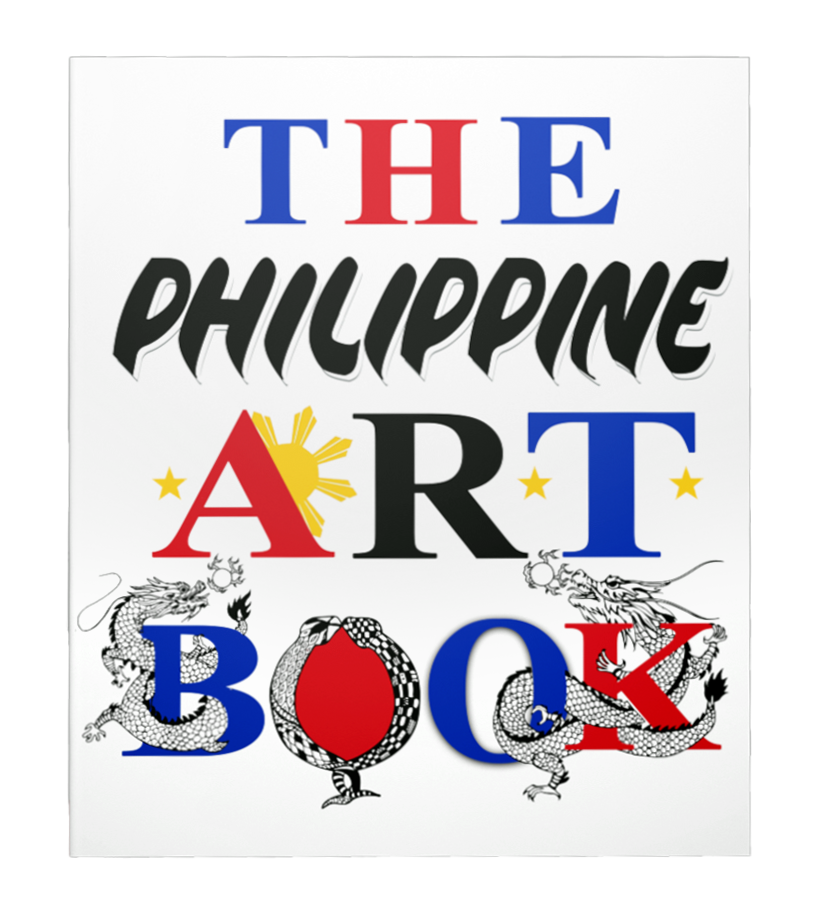

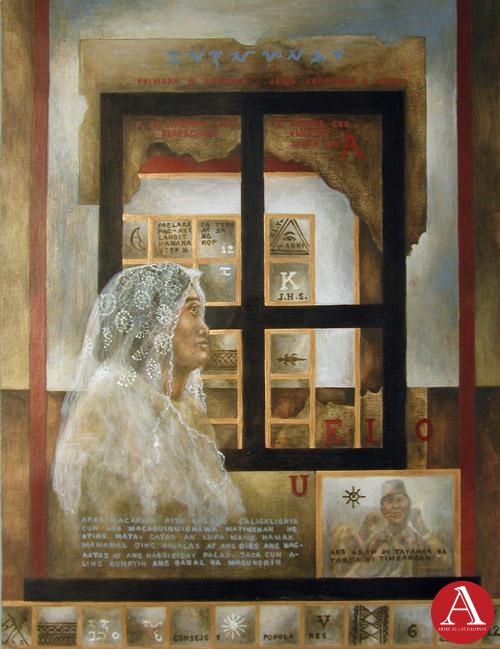

Kasal (1993)

What was the status of the art scene during the mid-1980s? Who were your contemporaries?

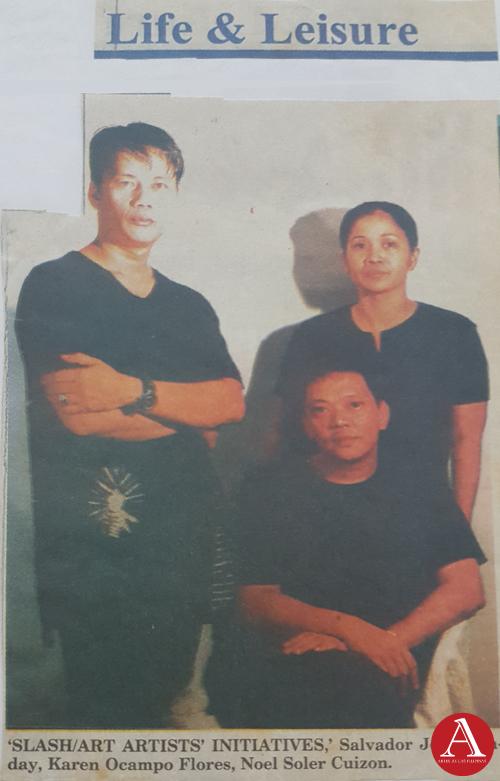

The mid-80s up to the early 90s was like a Renaissance of sort. After the EDSA Revolution, there seem to be a fermentation of new creative expressions that brought young artists together. This is in congruence with each other’s search for national identity and new expressions. There were a lot of biennales and international shows interested in Pinoy art. The scene was not so market-driven then and the collectors didn’t just acquire artworks; they conversed with artists and discussed art processes and theories. They tried to understand where the artist was coming from. Most of them became good friends even after they stopped collecting. We, the young artists enjoyed doing art and exploring new approaches in our craft. We were not so much concerned with our financial advancement. I was more concerned about peer validation though (laughs). Romantics as most of us were, we, became more interested in exploring other forms of artistic engagement through community involvement, advocacies and informal art education. My contemporaries are Karen Ocampo Flores, Mark Justiniani, Elmer Borlongan, Antonio Leaño, Yasmin Almonte, Salvador Alonday, Alwin Reamillo, among others.

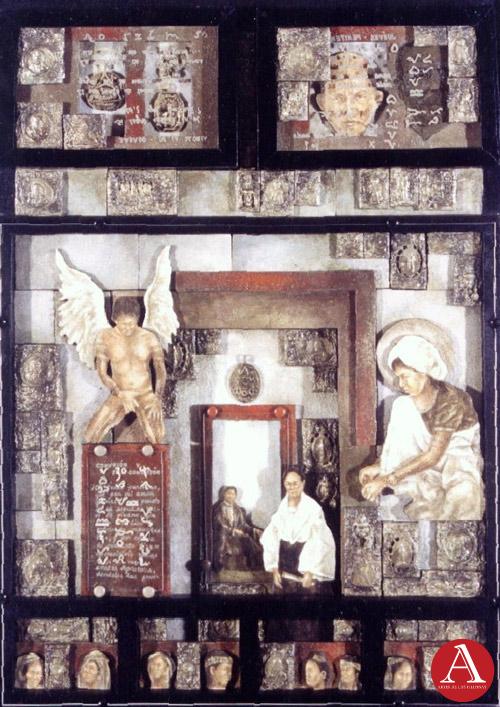

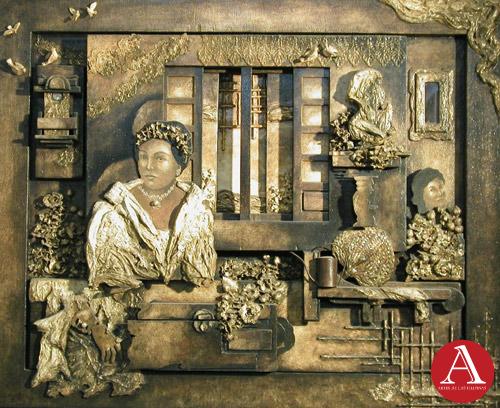

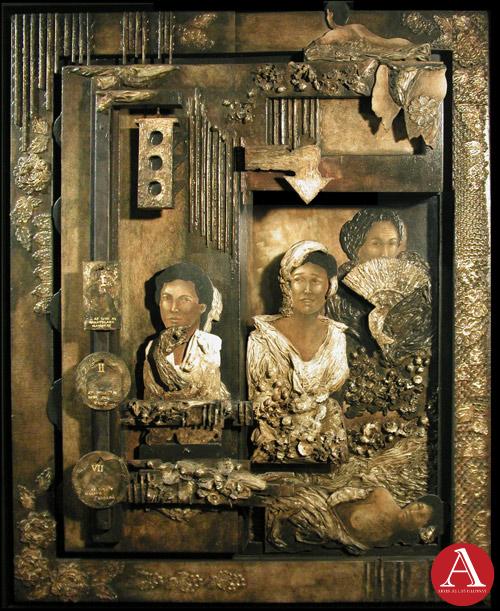

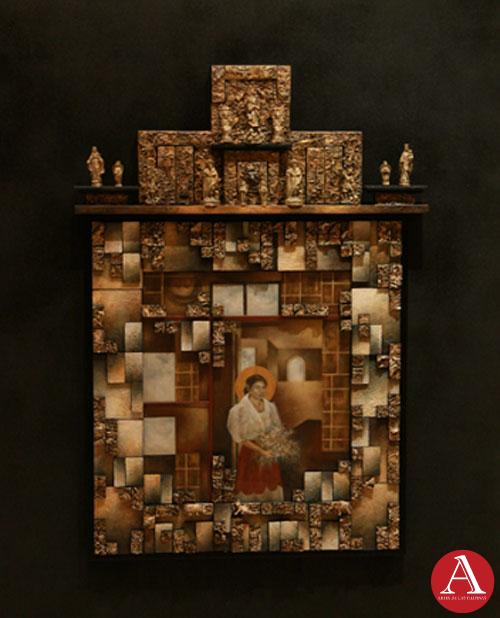

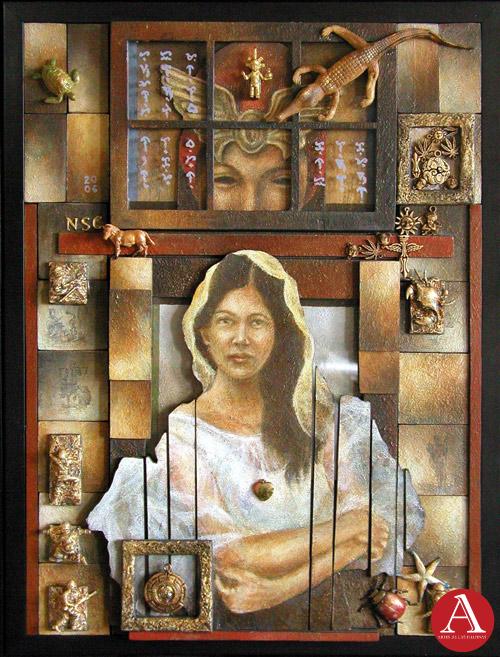

Nuestra Señora de los Sufridores (1994)

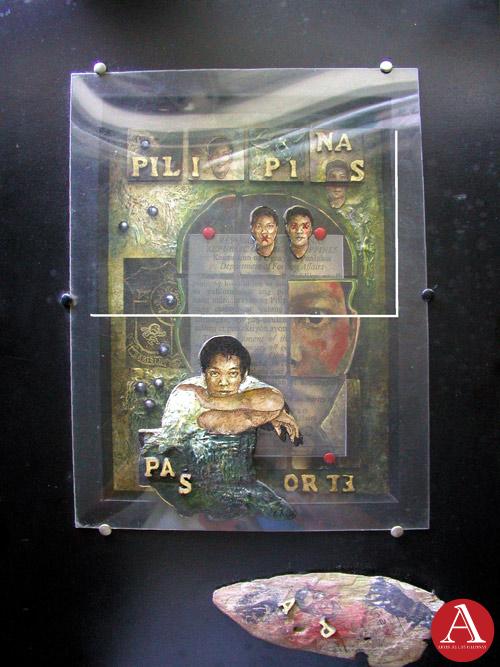

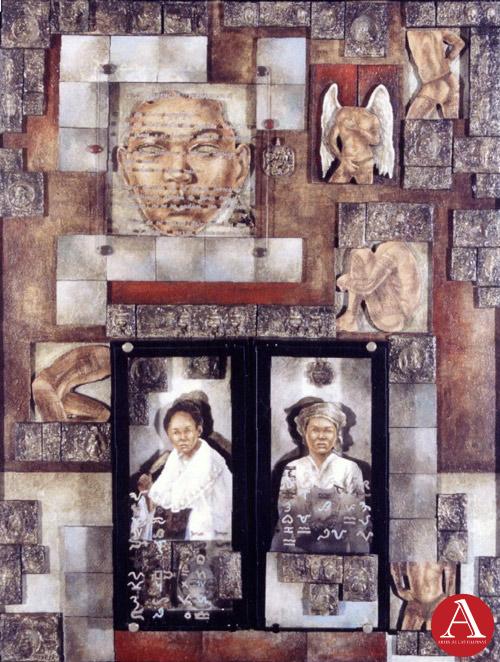

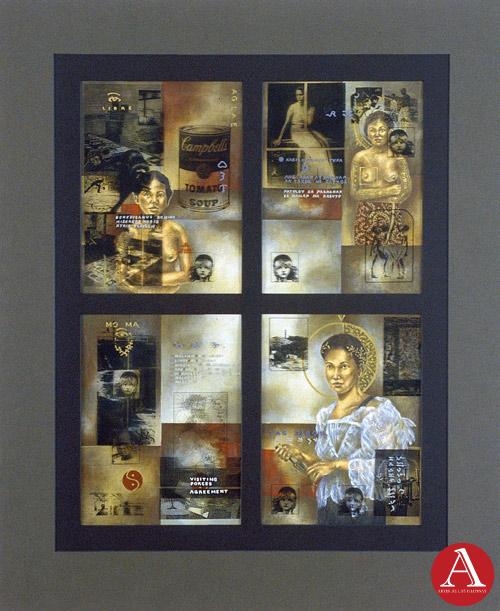

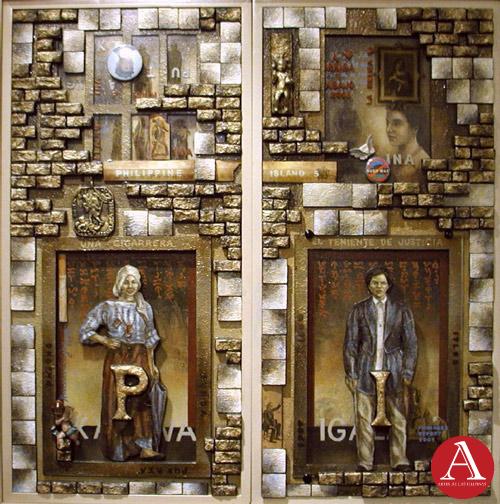

Pasaporte (1995)

What made you decide to pursue Fine Arts in college?

I have always been interested in drawing and other creative stuff so I thought that Fine Arts was the right course to take up after high school. On the outset, I had the impression that art was purely about aesthetics until I entered art school and became aware that it’s not just about honing your skills. You have to learn about translating perception, improving visual communication, and understanding history and theories. Since then, it has always been my concern to strike a balance between theory and practice. I think I was also inspired by my lola and aunt, Brenda Fajardo, who was then very active in theater, visual arts and other creative activities. Their artistic energies were nakakahawa. Growing up with two creative minds and having been exposed to various creative endeavors became an impetus for my future artistic pursuits.

My father, on the other hand, was very much against my decision to take up Fine Arts after high school so I enrolled in Architecture instead. My freshman year was a disaster; the rigidity of instruction and discipline particularly on mechanical drawing didn’t appeal much to me. When I shifted to Fine Arts years later, I saw myself veered towards the same direction that I had refused to accept before. The irony of it all is that every work in my succeeding years in art school tagged on the visual organization of design patterns, grids and structures akin to mechanical drawings.

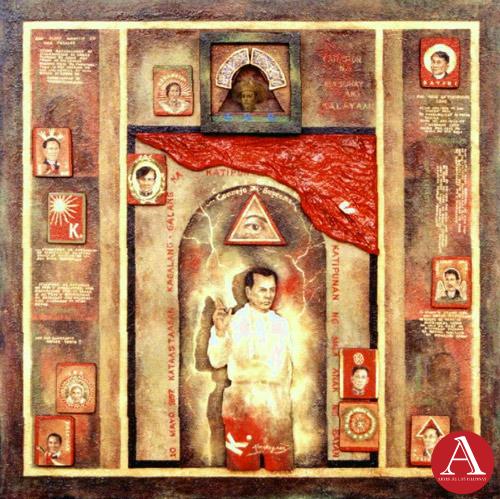

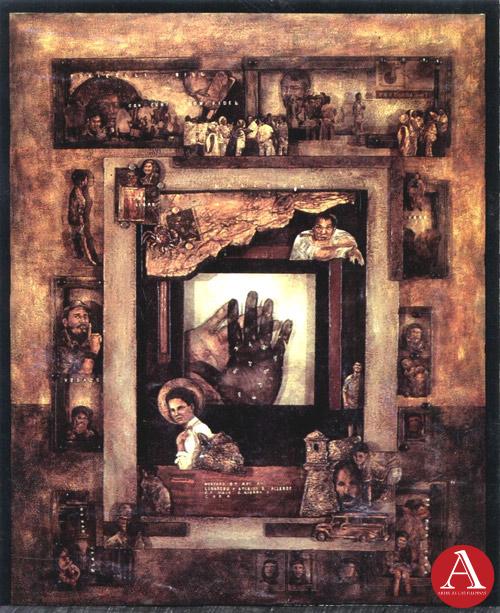

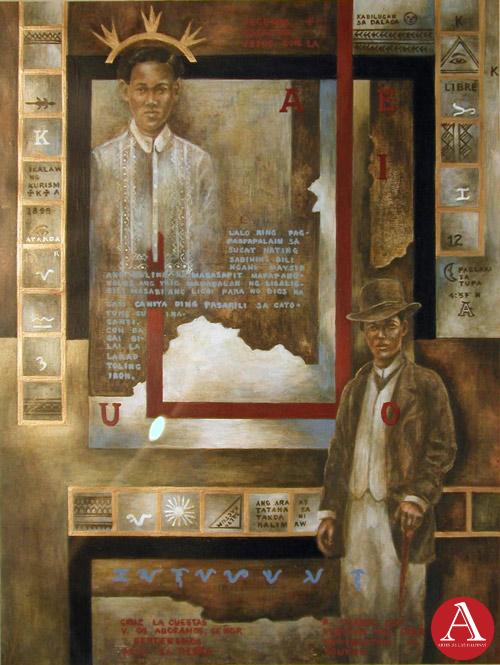

Si Don Andres May Pag-Asa at ang Pagbabalik ni Bernardo Carpio (1996)

Moro y Cristiano (1996)

Let’s talk about your student years. Who were some of your memorable professors in Fine Arts?

In my formative years, there were Ibarra de la Rosa, Angelito David, Paul Dimalanta and Renato Ong, Pandy Aviado, Boy Rodriguez Jr., Lito Mayo. Iba’t-ibang schools of thought ang pinanggagalingan nila. I think we had the best roster of teachers then. I learned a lot from all of them with regard to techniques and visual perception. Roberto Feleo was my undergraduate thesis adviser so he has influenced me a lot. Informally and vicariously, I was also influenced by the social realists like Antipas Delotavo and Egay Talusan Fernandez, who were both graduates of PWU and to a great degree, the late Santiago Bose.

Occasionally, I would sit-in at Angelito David’s watercolor class. Since I followed a new curriculum when I enrolled at PWU, I wasn’t able to formally enroll in his class. But I learned a lot of techniques from him, obliging myself to follow all his instructions. But he didn’t realize that I was not legitimately enrolled in his class until the last quarter of the term. I never submitted any of my finished works for assessment and would just listen to the evaluation of the works of other students in his class. It was a vicarious learning experience.

Walang Kupas (1996)

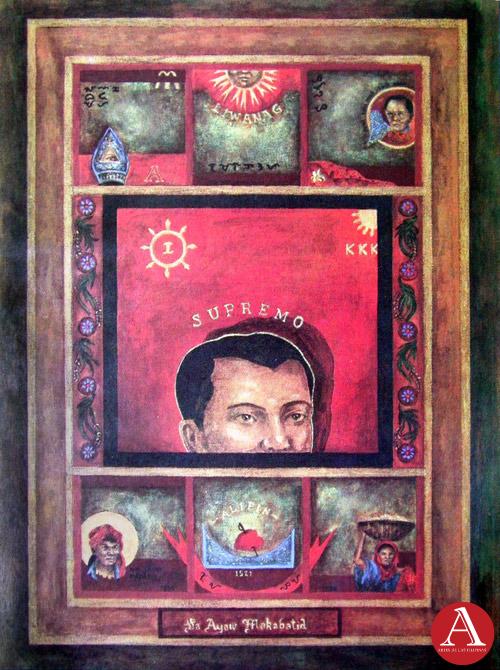

Sa Ayaw Makabatid (1996)

What did you learn from Ibarra de la Rosa?

Ibarra de la Rosa trained us to embrace discipline which we obtained through hours of studio work. I think he did put more weight on studio routine. We would learn the rudiments of painting more than scrutinized concepts and theories of art. He was also quite strict with deadlines. I remember how he would give us the same time frame to finish a 3’x3’ canvas and a 1’x 1’ canvas and how he would occasionally throw half-baked plates outside the window. It was unthinkable at the time and very taxing for a lot of us students. I didn’t like the severe directives then but looking back now, I must admit that it was imperative to studio practice.

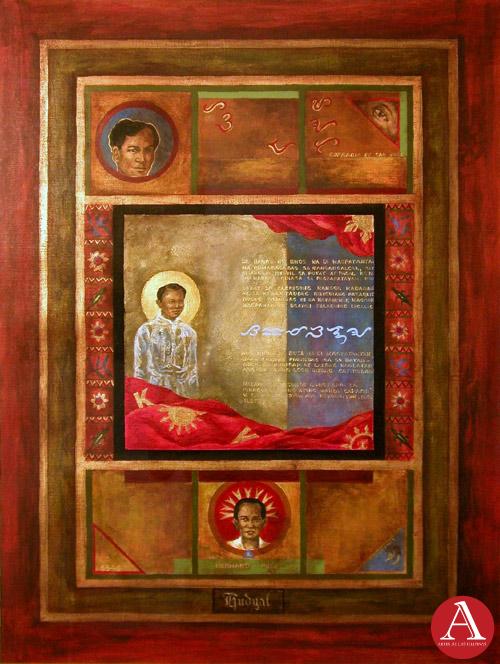

Hudyat (1996)

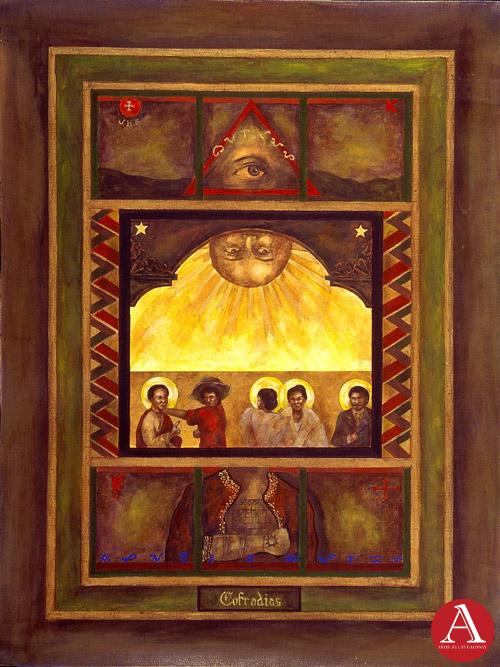

Cofradias (1996)

How about Boy Rodriguez?

Boy Rodriquez taught us all about the concept of play in terms of approaching our form, subject and content. He was very particular with how we understood the intricacies of the medium which included the basic techniques and approaches of printmaking. What I enjoyed most in his class was the limitless possibilities of expressing our ideas through various processes. The exploration even went beyond the traditional mode of instruction wherein we were allowed to break the rules once we’ve had the grasp of them.

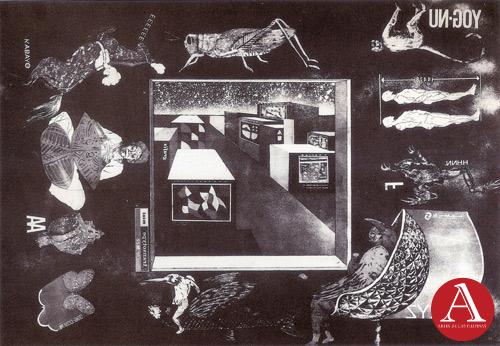

Lito Mayo's Komersiyalismo (1976) which Cuizon appropriated for the TutoK Kargada show at the Ateneo Art Gallery

In what way, did Lito Mayo influence you?

In the middle of the term of 1981 or 1982, Lito Mayo started teaching at PWU. I was transferred from Ibarra's class to the new instructor. We were, I think, around eight students, the delinquent ones who refused to follow Ibarra's instructions (laughs). Of course, I was so frustrated at first but when I met Lito Mayo and started holding classes with him, everything became a journey in exploration and experimentation. For the first time in art school, I felt so motivated to work and felt alive! I made a series entitled Dream Saga in Lito's class and he was very encouraging. It was the first of that series. I lost everything after I graduated. Now, if Lito passed away in 1983, that class must be before the summer of that year. When summer came I even had dreams of Lito that I was conversing with him under the trees sa vacant lot ng Fine Arts in PWU. He was standing beside his motorcyle in his usual black leather pants and jacket. The words he was uttering were inaudible. Mga three nights ko siyang napapaniginipan. Then days later, I went to PWU to check my grades only to find out na ililibing na siya in Batangas. I lost a teacher who had always encouraged me to explore creative possibilities. Lito did not influence me in terms of style but he guided me towards artistic exploration. A year before I had my heart attack, an aunt's friend gave me a Lito Mayo print which I was able to sell to an old friend after my angioplasty to cover my medicine expenses. It was against my will and among other works I thought that maybe Lito was trying to tell me, "O ayan ah! Nabenta mo work ko, pambili ng gamot mo." Si Lito Mayo, nung estudyante pa kami lagi akong binibiro,"Huwag ka masyadong seryoso, bata ka pa!" He was like a barkada teacher to me.

In 2008, I was part of the show, TutoK Kargado at the Ateneo Gallery curated by Bogie Tence Ruiz. He asked us, participating artists, to create a visual dialogue between contemporary Filipino artists and the modern masters in the collection of the Ateneo Art Gallery. The show examined nationhood, modernism, critical self-recognition, political complexity and proposes that art practice comes with an inseparable charge, a context, an implication that cannot be distilled away into absolute form but has to be grafted and manifest by and in such form to fully address the era it came from. My response to the curatorial plan was to situate the works of Lito Mayo and Brenda Fajardo from the gallery collection in a discourse about the nature of influences. These two great artists have influenced me in my artistic journey so I envisioned an installation piece that will simulate a scene where I would be paying homage to them. And as if to continue my “Dream Saga” series for Lito Mayo’s Techniques class, the installation took a facsimile of fragments coming from a dream. The material set up imitated a venue where I would be in conversation with my two masters/ mentors. In my assigned space, a long table and two wooden chairs were hanged upside down from the ceiling and another chair was positioned on the floor facing a wall where their works were to be installed. I photocopied their other artworks that were not part of the Ateneo Art Gallery collection and had them laminated. I hanged the plastic-coated estampitas into mobiles of sort to create the flow of a suggested tête-à-tête with them regarding their artistic explorations – represented by a range of their creative outputs.

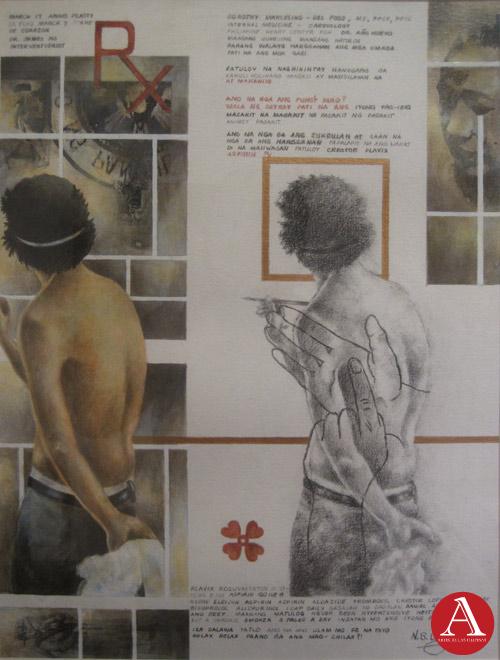

X (1997)

After A Hundred Years of Dreaming (1997)

Tell me about your student works.

The early works I did in school were the usual art stuff, the basics, and some "lolo" art as my students label them now when they see: landscapes, still life, portraits and the like. I began exploring new visual idioms when I reached my junior year under Roberto Feleo with the intermediate art subjects that dealt with problem solving in the arts, exploration of materials, developing your own visual language and understanding visual metaphors in artistic expressions.

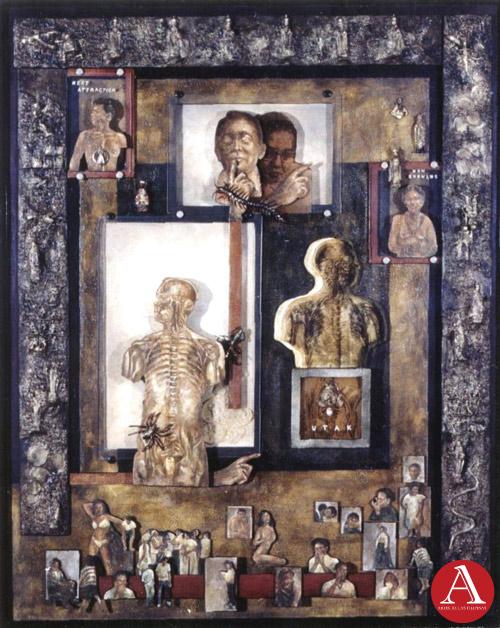

Anatomy of Displacement (1997)

Correspondence of Ironic Metaphors (1997)

What was your undergraduate thesis about?

My undergrad thesis came about with the challenge put forward by my adviser, Roberto Feleo during our Art Workshop classes prior to the thesis: to explore various possibilities of involving the audience in a dialogue with your work, by means of a format that will entail a totally different method of interactivity. As a response to this visual problem, I wanted to address the normal reaction when you’re confronted with a "Do Not Touch the Painting Please.” instruction commonly seen in galleries. I decided to take the reverse position as the premise of my ‘manipulative’ course of action wherein the audience can literally touch the artwork to arrive at an understanding of the artist’s intention and narratives. My method was to initially set the main theme for the two-dimensional piece and encourage the viewers to manipulate some of the components within the pictorial plane. Upon going through a tactile experience with the artwork, the supposition was that an engagement could be forged to allow different modes of interpretation.

In addressing the issue at hand, I started exploring my visual discourse by creating assemblages of cut-out wooden pieces, multi-layered platforms and found objects. Instead of just establishing the pictorial surface through the formal elements and principles of design, I had to make a decision on how to achieve an effective visual representation while translating the interactive aspect of my mixed media works. The fruition of these possibilities was conceived when, one day, my four year old nephew visited me in my studio and started playing with all the elements of my work left on the floor, which, at that time, I didn’t have a clue on what to do. When I saw him arranging the detached pieces of the unfinished work, the idea of making my artwork interactive was conceived. What if I put pockets and platforms with various cut-out figures where the audience could interchange some of the work’s components or even intervene with the composition? It took me a while, however, to integrate the concept of how I was previously trained to put things together as a painter. So as not to lose track of my direction, I would always follow the creative process that I’ve been accustomed to in handling two-dimensional planes. I would start with the concept, do some rough studies and then proceed with a compre. And as I was just starting to explore this method, I would even make a maquette before working on the actual piece. With this scheme, I was able to achieve both goals of creating an effective pictorial organization and motivate the audience to physically interact with the components of my artwork.

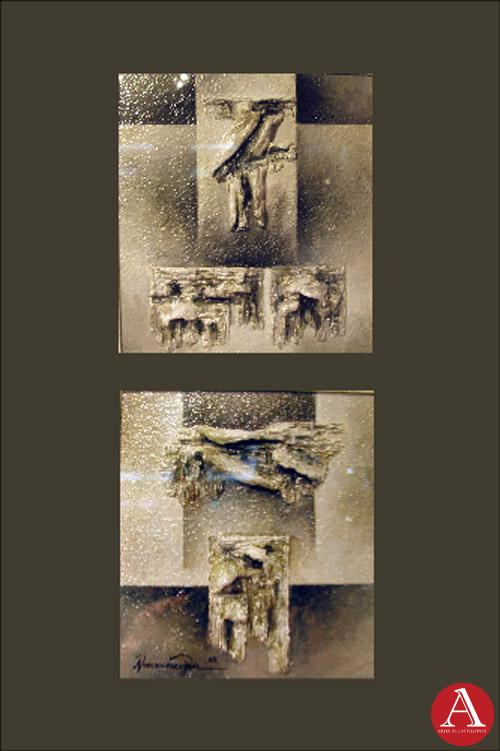

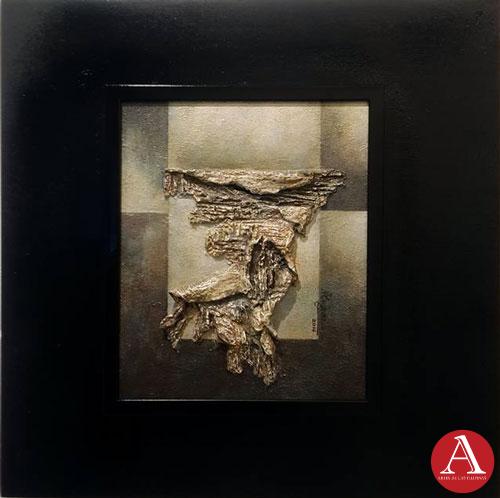

Cerebral Decolonization 2 (1997)

Deconstructing Icons 1 (1998)

What media do you work in?

Through several experimentations and after acknowledging the importance of learning the basics, I was able to develop new ways of seeing things that helped me in translating concepts and narratives through my own visual language. Exploration of non-traditional materials was positioned in understanding how I could effectively articulate my intentions. Medyo mahirap ito kasi I’m not so good in articulating verbally what I wanted to express visually. It has always been a lot easier to illustrate ideas visually rather than talk about them.

My work took the non-traditional direction with mixed media works and interactive assemblage. It was a subconscious application of a child’s play or how I would visually react to stimuli in my younger years. My approach would basically start with how I would handle pictorial composition in a two- dimensional pictorial plane before it evolves into its final assemblage stage. In a way, I’m still consciously following my basic training as a painter. Eventually and as I develop my style and visual language, I became more comfortable with addressing the materials as they were and would directly address the art problematic without reference to my academic foundation.

Deconstructing Icons 2 (1998)

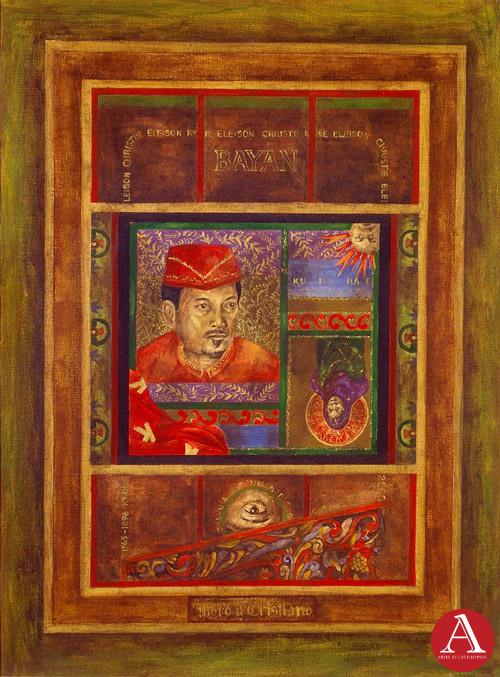

Deconstructing Icons 3 (1998)

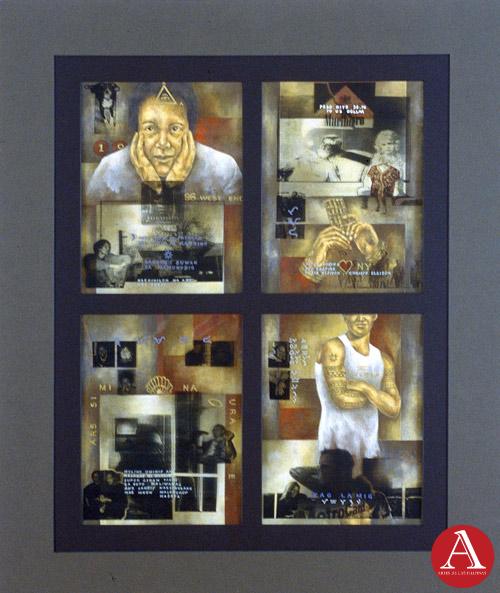

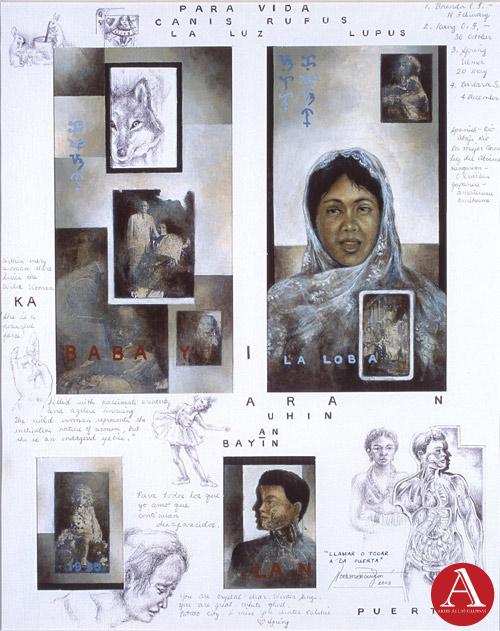

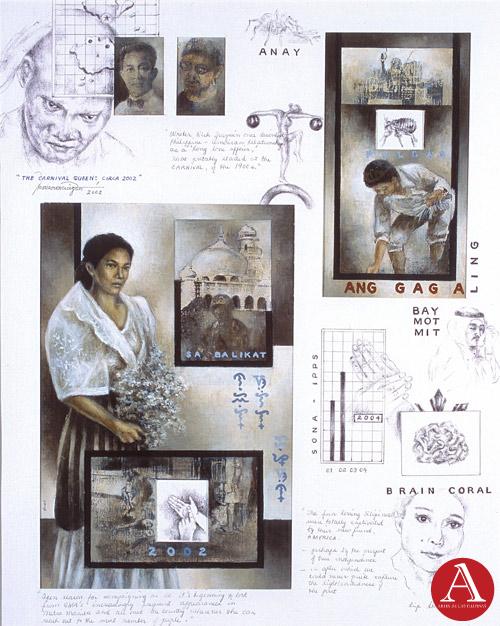

What themes did you explore the most?

My works took the direction of engaging in an editorial using visual metaphors that deal with contemporary life: socio- political issues, lessons learned from history and a critical assessment of other cultural issues.

Centennial Jargon (1998)

Auto-Letrato (1998)

What was the first gallery that showcase your works?

I started with Hiraya Gallery in 1988 and I was in its stable until 1998. I had three solo shows there. That’s also where I learned a lot about art practice through the tutelage of the late curator, Bobi Valenzuela. Artists would gather around the venue to discuss everything from visual arts to music to history and theater, philosophy and literature. I also honed my exhibition design skills there also under the mentorship of Bobi Valenzuela.

Philippine Star (1992)

Tell me about your first exhibition.

Masaya na mahirap at overwhelming. Where do I start here? There was a call from Bobi Valenzuela to all the artists at Hiraya to respond to the upcoming national election. The curator wanted to mount a show in time for the election, so Christmas pa lang of the previous year, inupuan na namin ng ilang mga artists yung project. My take on this was to do an inquiry and assessment on each candidate and translate my opinions visually into assemblage pieces, the interactive ones. Ang daming conflicting ideas plus dami rin turncoats, lipat ng partido and compromises regarding each candidate’s platforms. I rented a studio space in a remote subdivision at Fairview to finish my series so I had the dailies to inform me about the progress of the "circus.”

Come May 1992, I was informed that the artists did not respond to Bobi’s call. I can’t blame them, para naman talagang circus yung election, medyo magulo in a sense. So hayun, he just mounted my works at the Mezzanine of Hiraya, no fanfare, in fact, wala ngang opening. The collection was just up for viewing. I think my first solo exhibit was not an official one until the press picked it up (laughs). Before I knew it, may interviews na and later lumabas na nga yung mga reviews about "Hugot-Bunot sa Mayo Onse” and my claim to fame of being the only artist to have mounted an exhibit about a national event (laughs). Little did I know na ako nga lang pala ang may responde sa Philippine art scene about the election. I was even surprised when I heard from the gallery that a Japanese collector bought the seven works and later brought it to Paris so my works for that show were never properly documented.

Two weeks after the exhibition run and after the announcement of a new Philippine president, I was invited for a move-over show at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Pandy Aviado, who has been my professor at the Philippine Women’s University and at the time, the Coordinating Center for Visual Arts director of the CCP invited me to have a solo at the Small Gallery with a revised title: “Hugot-Bunot Kinapos.” I had to add four other works and an installation piece of painted ballot boxes, para di kumalog ang mga piyesa sa Small Gallery.

Kasal (1993)

For the ideas of your own exhibitions, how do you try to be unique in concepts and executions?

Ain’t hard to be unique (laughs)! But really, it has never been an issue with me. I believe in collective memory and parallel interpretations so I just follow my thoughts and assess the topics that I want to cover before I work on a piece. I let my creative side take the upper hand and allow visual surprises to take their course (laughs). Seriously, I bleed every time I start with a new work.

Tag-Sibol: In Search of Venus (1999)

Tag-Lamig: Waiting for Spring (1999)

Have you heard of comments that a certain artist has done the same kind of work that you did for a particular exhibition?

If viewers have mentioned before that my works looked like that of other artists, I interpret them now as more like being influenced by certain artists. The character of visual persuasion and predilection comes into play here. Each artist influences one another in so many ways. So even if the initial remarks were “your works look similar to the works of so and so artists;” their comments were dissipated upon closer scrutiny of the pieces. After viewing the exhibition, they would acknowledge later that what I have been doing in my visual explorations were totally different from their references.

Of Cryptic Appropriation and Identity Politics (2000)

When you are in the process of preparing for a solo show, who is the viewer you have in mind?

Students, art aficionados, academicians, critics and patrons. In that particular order.

The Pilgrim Sorcerer (2000)

Do you think a painter can become commercially successful without receiving any award?

I think so. It’s just a lot easier if one gets validation from the establishment.

Ang Tala-Arawan ni Mang Idong at Don Juan

I understand that you are an old hand in receiving awards. Do you remember your first painting that won third place at the Hiraya Painting Competition? What is this painting about?

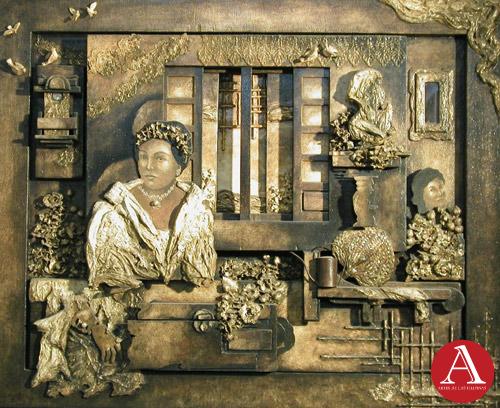

The Hiraya Gallery and Titanium Group Painting Competition was an open call to all Filipino artists but there’s an age limit of forty years old. That year’s winners were Nelson Ferraris, first place, Php 30k, Justo Cascante III, second place, Php 20k and myself in third place, getting Php 10K. Ang Tala-Arawan ni Mang Idong at Don Juan, my entry for the competition talks about the dynamics between constituents in the context of hierarchies inside a very feudal system. It focuses on the human aspect within the social structure. It speaks about the undying loyalty of a servant to his master that started with an anecdote about my maternal great grandfather, Don Juan, taking custody of Mang Idong since he was eleven years old. A remarkable relationship between the two was forged. The latter feeling indebted to Don Juan, continued to serve the family even after the demise of the patriarch and upon the outbreak of the Second World War, Mang Idong decided to stay with the family and had chosen to devote his time to my Lola Naty, who was amongst the other thirteen Fajardo siblings and her two daughters, my mom and aunt, until his last remaining days. I’ve always admired him from a distance as I hear a lot of stories about his unrelenting dedication to our family. The artwork was my way of paying tribute to the man.

In this work, I’ve taken up on the methodology of autobiography and biography as a theoretical model. The interchangeable pieces here were cut-out wooden figures of both Don Juan and Mang Idong, alternately, taking center stage within the social strata, a deconstruction of hierarchies as depicted in the pictorial surface. It simulated a journal and a portrait reminiscent of the olden days brought into play with the colors, tones and texture of the work. The contention here was that perhaps portraiture, which was reserved for the wealthy families during colonial times, positioned from another standpoint, might serve as a powerful visual form to suggest intrusion in structures within the social echelon, a leveler of sort.

Istasyon (1994)

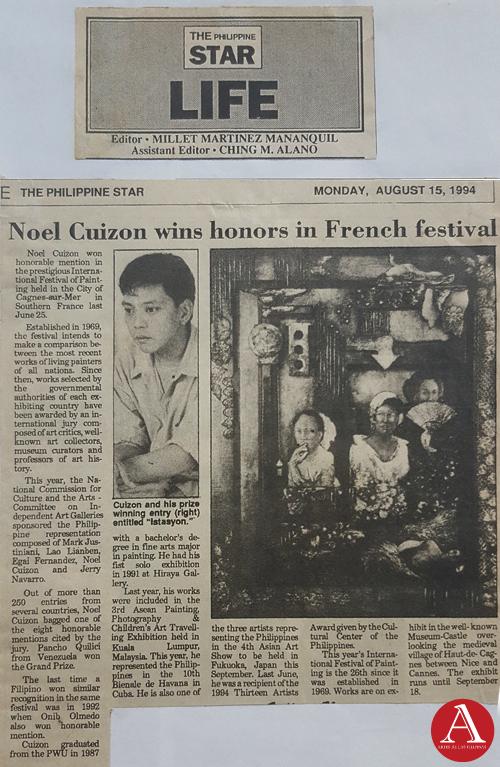

Philippine Star, August 15, 1994

Let’s talk about your entry, Istasyon, that won honorable mention at the International Festival of Painting in Cagnes-sur-Mer, France in 1994. What is this work about?

The participation to Cagnes-sur-Mer was through the initiative of the Commission of Galleries under the National Commission on Culture and the Arts in 1994. The selection of artists represented that year was comprised of Egay Talusan Fernandez, Mark Justiniani, Lao Lianben, the late Jerry Elizalde Navarro and myself. Two years prior to that, Onib Olmedo won the same mention-du-jury award that I received. I never knew if there was a cash award.

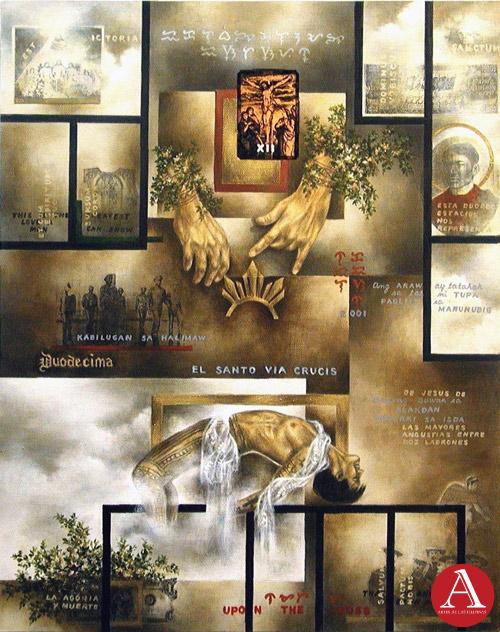

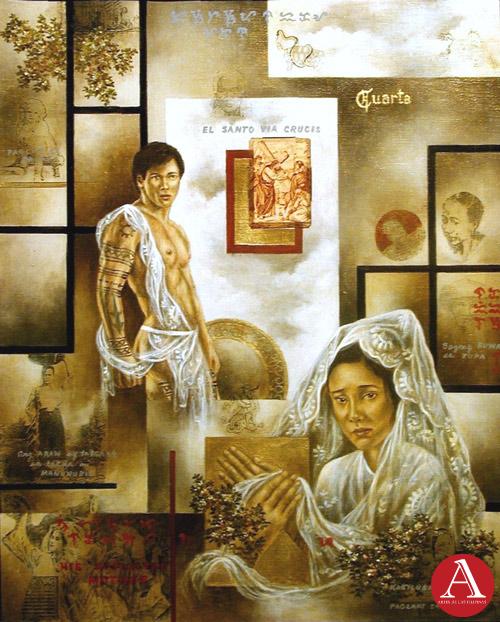

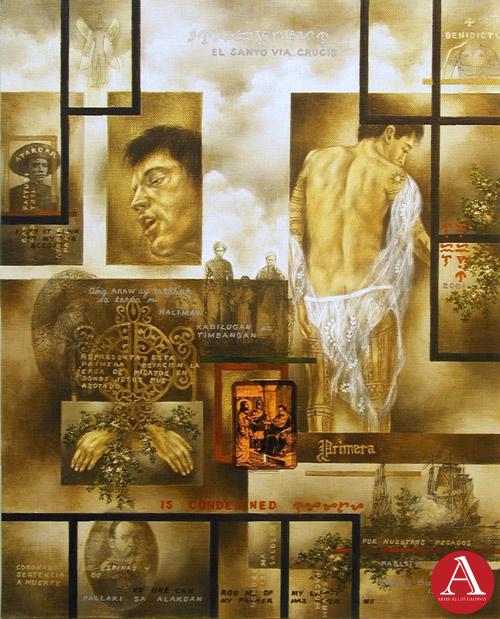

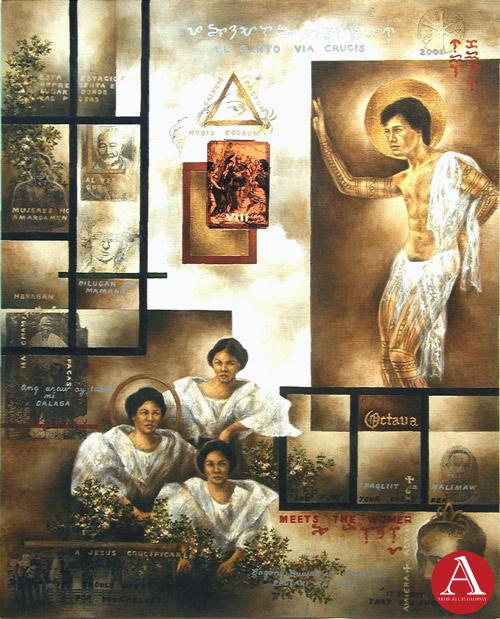

Istasyon, my entry for the competition, was from the collection of works after my second solo exhibition, Pasyong Mahal at Hiraya Gallery. I employed the archetypes of Catholic Church rituals as visual allusions to comment on the political situation of our country. Appropriating the Stations of the Cross as an iconography to articulate on the current predicament of the Filipinos, I created a Christ-like image of a man which can be interchanged in various stages within the pictorial plane.

The central figure was positioned in a retablo and can be altered five times with the other interchangeable figures concealed on the side pockets of the wood assemblage. The scenario created suggests the ageing of the Christ-like image as you take the wooden cut-out figure and arrange it on its assigned position. This denotes that in the passing of time, nothing much has really changed in our society; not even after the cathartic EDSA revolution nor during the then installed Ramos administration. The work was an offshoot of the works I did for my first solo exhibition, Hugot-Bunot that tackled issues surrounding the National Election of 1992.

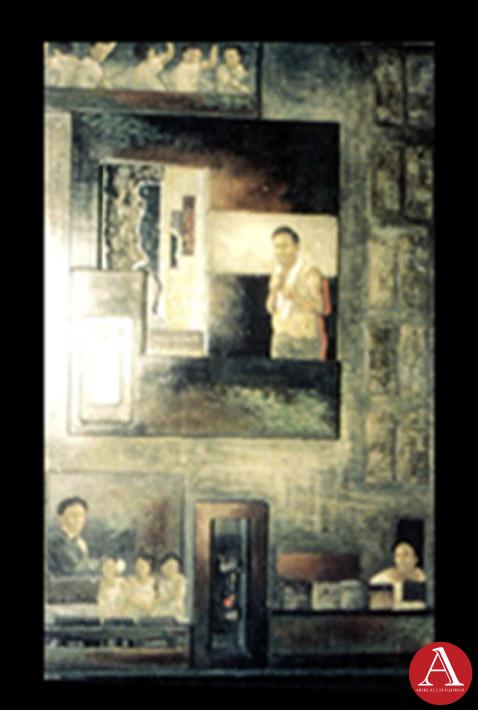

Galeriya 2000, Installation for the13 Artists Award Exhibition, CCP, (1994)

In 1994, you received the Thirteen Artists Award from the Cultural Center of the Philippines. What did you prepare for the exhibition?

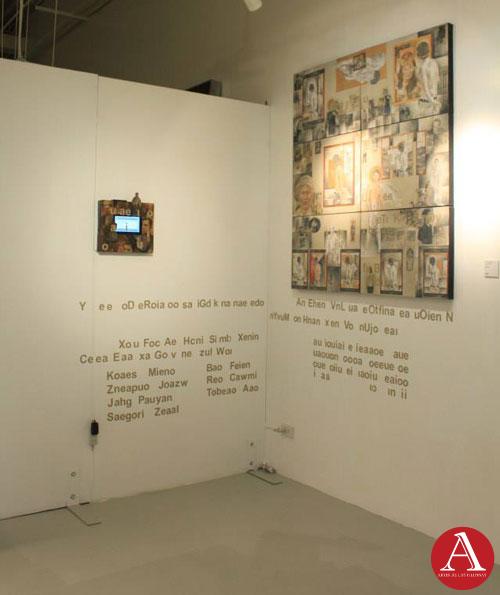

I did an installation piece with the intention of addressing the state of the arts in the Philippines. It was a critique on the popular modes of expression prevalent in the contemporary art scene then, a reflective of the social conditions of the period. By re-creating these works in various styles and persuasion which were endemic at the time, I made a parody of the social, political and economic aspects within the art system. This was achieved by putting up my own gallery within a gallery – Galeriya 2000, at the Bulwagang Juan Luna of the Cultural Center of the Philippines which I think was the most appropriate venue to generate a discourse on a topic like this. In all appearances, the works suggested pure notions about the conditions that define artistic tendencies, with reference to styles and affiliations. But on second look, the content of the exhibited works in the appropriated setting echoed the state of the nation as well.

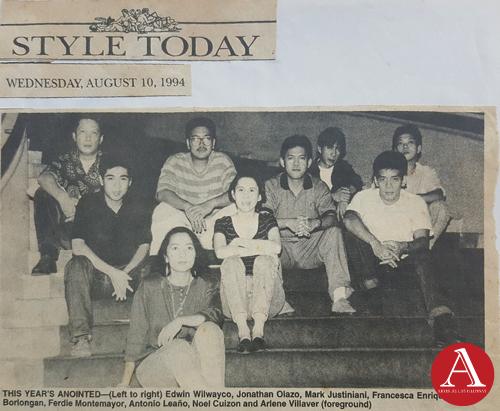

Style Today, August 10, 1994

Among your awards, which one was memorable to you?

I treat all my awards as pats on the shoulder, some kind of validation to carry on with what I’m doing. But the most memorable one, I must say, is the Thirteen Artists Award, mainly because of the alliances formed among colleagues during the six month preparation for the show. The discussions on our processes gave us profound insights about each other’s diverse philosophies and approaches to art.

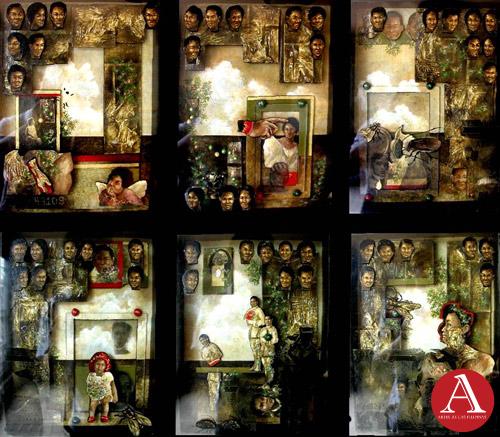

Let’s talk about your key works. Can you cite some of your favorite artworks and why you hold them important?

I’m predisposed to value these key works not simply for aesthetic reasons but for various opportunities they had offered me in the process of mapping my visual trajectories. I have clustered some works to establish the significance of their convergence either in form, subject or content. The course of creating a linear direction in my artistic passage can be defined by these artworks.

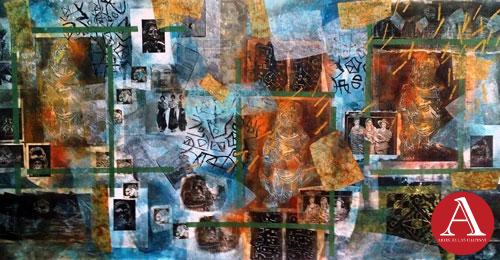

Ipinagbiling Kahapon is what I regard as my iconic work. It’s an interactive piece that was distilled through several stages of restructuring until it reached its completion. The physical components within the pictorial surface came from various periods of pictorial investigations that directed me towards the realization of my intention – to involve the viewer in physically mediating with my artwork and to keep the integrity of the work’s visual organization. This work evolved from a montage of found objects and small paintings attached to several elevated wooden panels of different heights that conjured to depict conflicting post-EDSA sentiments. Its various elements were done in different periods, set and mounted to construct the work’s background. A clear flexiglass is then installed to cover the layers of complex images and to suggest a veneer of separation from the work’s more compact foreground. The intricacy of composition underneath the acrylic plastic was muted by this device, re-creating some sort of a diorama. In appropriating Aurelio Tolentino’s Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas stage play as a visual metaphor to articulate on the theme, I shaped three cut-out wooden figures of Inang Bayan, the play’s main character, as my central subject. They are to be positioned one at a time in a stage-like structure that adds another dimension to the artwork. The construction of a raised area is introduced as a compartment that served both as a drawer to conceal the two other images and a platform or stage with biomorphic cut-outs that covers it as well as set a directional device to lead the eye to the focal point of the composition. Considering the crucial decisions I had to take in to carry out the plans for the piece, the delivery of Ipinagbiling Kahapon was a high point in my artistic passage. When it was first exhibited in a group show at Hiraya Gallery, weeks before it was sent to the Makurazaki Biennial in Japan, I had this strange feeling that the work was conversing with me and not unlike the wooden marionette of Mastro Geppetto, had assumed a life of its own. The rest are the following:

2. Someday I'll Go Back to Heaven (1997) and Hanggang sa Muling Pagpanaw

Someday I’ll Go Back to Heaven (1997)

Hanggang Sa Muling Pagpanaw

Hanggang sa Muling Pagpanaw and Someday I’ll Go Back to Heaven are works created on two separate artistic periods that seem to have a strong relationship in terms of form and content. The first one was a takeoff from my traditional painting approach and my first attempt to deal with spatial problems outside the bounds of a pictorial plane while the latter set the mode for a more complex compositional scheme within layers of planar structures. They are both transitional works, like threshold guardians who summon you to leave your comfort zone and face the challenges of the new. Employing the model of psychoanalysis in both works enabled me to

address a philosophical subject matter while giving equal emphasis to the theme and construction. Metaphorically, the process afforded me to delve on a topic that has always fascinated me – the complexities of death and dying.

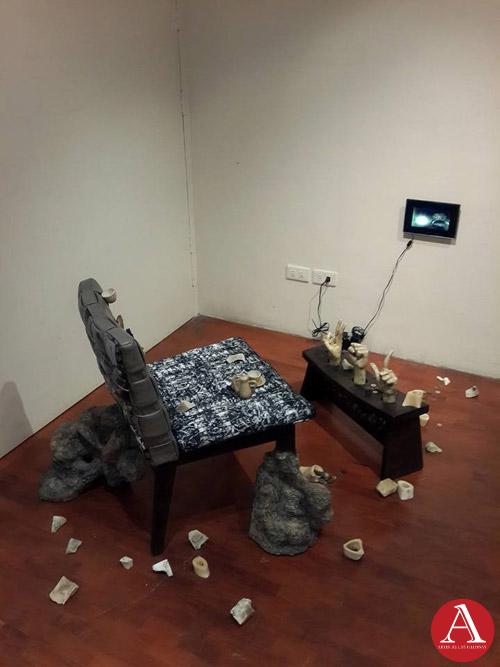

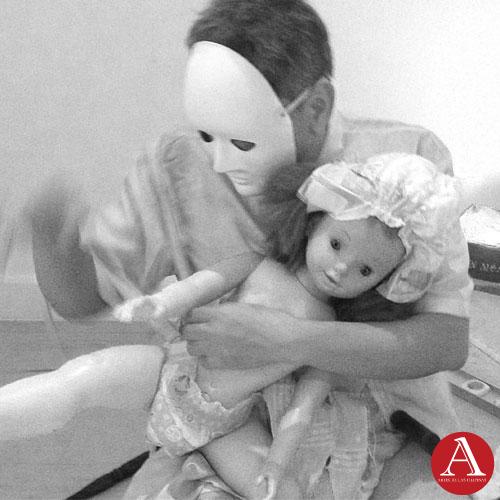

3. In Transit 2011, Performance/ Installation from the Nothing to Declare Show at the Blanc Compound, Yuchengco Museum and the UP Vargas Museum

In Transit, Performance, Nothing to Declare Exhibition, Blanc Compound (2011)

In Transit, 2011, Performance, Nothing to Declare Exhibition, UP Vargas Museum (2011)

In Transit, 2011, Performance, Nothing to Declare Exhibition, Yuchengco Museum (2011)

In Transit (2011), a collaborative project with the Asia Pacific College Multimedia interns, was my response to the curatorial call from the

organizers and curators of the Nothing to Declare” Exhibition in 2011. It is a multi-venue and multi-pronged international art project aimed to contribute to contemporary discussions on migration, not only of people across borders but of forms and realities across time and space. The project focused on those who have nothing to declare – those whose marginality is a source of intervention and strength, of subterfuge and resistance, of constraint as well as change.

The work is significant in a way because it was the only piece that wasincluded in the three exhibition venues – Blanc Compound, Yuchenco Museum and the UP Vargas Museum, where the collaboration with the three associate curators: Karen Ocampo Flores, Claro Ramirez and Leo Abaya elucidated my viewpoint and intentions. This enabled me to translate my installation/ performance to various levels of interpretation as I redefine my space and comfort zones that mark the self and home within continuous states of transit. The installation/ performance echoed reflections on physical crossings, displacement and constant change that were common themes tackled in my interactive wood assemblage works.

4. BALITA: Pagbasa mula sa Pahayag ni Noel Celis and Primera, Segunda, Tercera

BALITA: Pagbasa mula sa Pahayag ni Noel Celis

Primera, Segunda, Tercera, Collaborative on the Bonifacio Wheelchair Project with Karen Ocampo Flores (2013)

The two chair projects, both collaborations with Karen Ocampo Flores are significant pieces primarily because the process gave me an

understanding of the value and intricacies of artistic collaboration. As a component of best practices in art, synergy in collaboration allows us to merge parallel narratives by means of resolving conflicts and visual tensions. Negotiations were forged as we arrived at a gestalt through the interaction of our individual styles, sensibilities and interpretations of the subject.

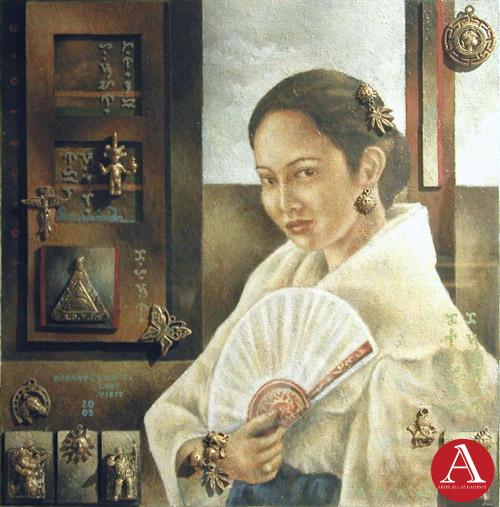

5. Visitacion a las Islas Filipinas (2016), Clio's Last Visit (2005) and Cuaderno ng mga Bayani (1997)

Visitacion a Las Islas Filipinas (2016)

Clio's Last Visit (2005)

Cuaderno ng mga Bayani (1997)

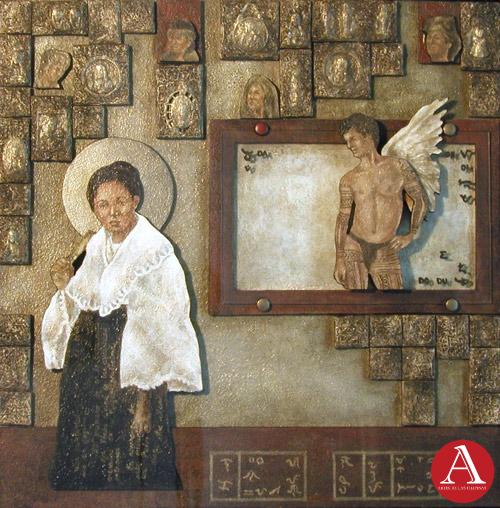

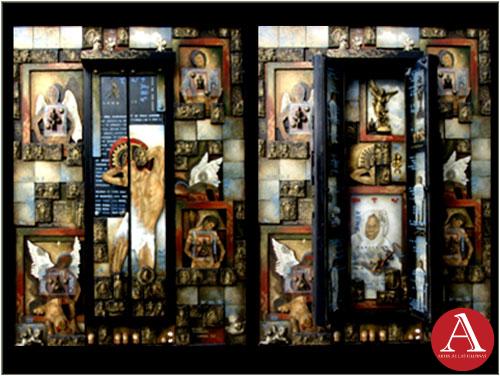

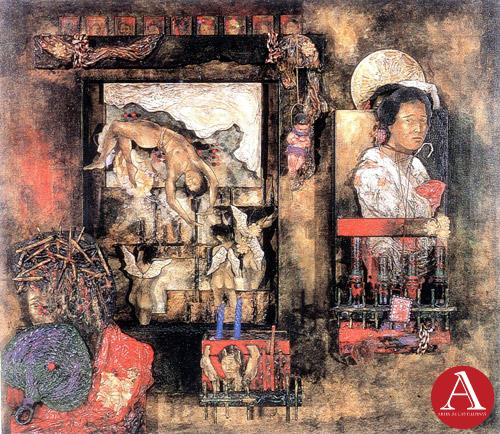

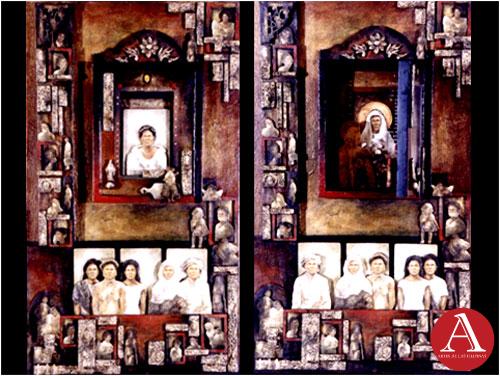

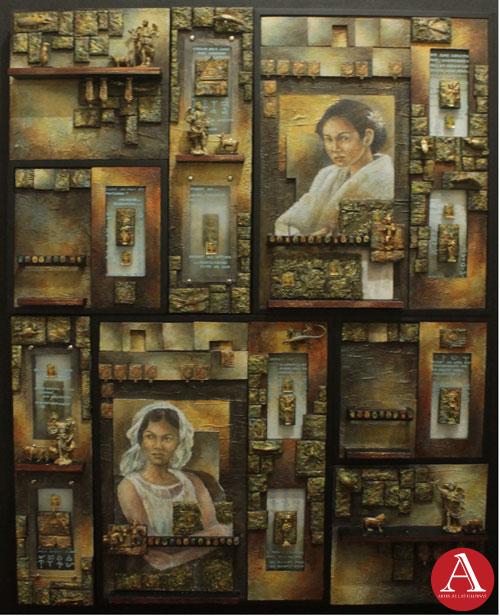

6. Aparisyon (1993) and Instituto de Mujeres (1996)

Aparisyon (1993)

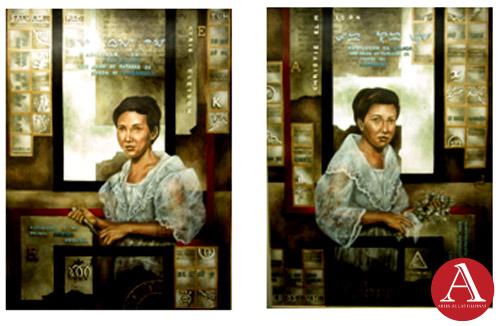

Instituto de Mujeres (1996)

Instituto de Mujeres (Left-central cabinet close and Right-central cabinet open) (1996)

What do you think is the profile of collectors who collect your works?

Diverse in terms of profession but I think they’re all interested in new modes of visual translations and artistic narratives. Most of them want something out of the ordinary like the best thing since sliced bread (laughs).

Duodecima (2001)

You’ve had numerous commissioned paintings, what are those that you remember most?

I always call the shots (laughs)! Luckily, with the projects that pushed through, all the clients gave me the liberty to do what I wanted to accomplish. There had been no compromise up to this time. If the deal went against my beliefs and principles then I abort the project even before it got started. There was one offer from an influential family of a historical figure to do a work celebrating the centennial of their grandfather. This project could have been my first millions from a single painting (laughs). After reading his autobiography, I politely declined the commission, thinking that the problem would be ideological.

Another business tycoon/politician from the South offered me 2M with the condition that I work on a collection very similar to my first or second solo exhibits, Money Down. Repeating myself in that manner was inconceivable even though at the time I was almost Php 20 close to prostitution (laughs). The offer was quite tempting but again, no negotiations transpired especially after he asked me: “How could you possibly price one million for your work when you don’t have a million in your pocket?” I digress. I offered him tea and refuse to concede to his whims (chuckles).

Cuarta (2001)

What is an ideal client to you?

An ideal client would be someone who’s willing to understand where I’m coming from as an artist. Someone who is inquisitive about my narratives and how I situate my personal experiences in the bigger picture. I think that spells the difference between our collectors back then. They understood the context of the works in relation to the artists’ creative process. I remember how we would even have long lunches or dinners with them, amongst artists’ friends and curators, just to discuss what our artworks were all about. We give them in-depth information about our processes and philosophies before they get to decide on which pieces to acquire.

Primera (2001)

Now let’s talk about some reviews and commentaries, what has been the best compliment said about you or your work?

“Awesome!” (laughs). “Profound!” (laughs). Mabusisi! Matiyaga! Intricate work! “Cuizon’s works make you think and not just simply view images…,” and another one would be “the artist’s viewpoint, depicted in his works helps you approach issues in a critical way, if these comments were good ones (laughs). Nakalimutan ko na nga kung sinong nagsabi ng mga ito.

On the other hand, I also received comments such as “Boring the works!” (laughs). “Your work looks like a Feleo or a Fajardo or even a Bose.” I believe that there’s such a thing called nature of influences. Tsaka mga idol ko naman talaga sina Santi Bose, Bob Feleo and Brenda Fajardo. I’ve learned to acknowledge analogous viewpoints as well.

Octava (2001)

Jerry Elizalde once reviewed your works. Can you tell us about his review and how you managed to call his attention?

To be daring and ambitious was the curatorial direction set by the late Bobi Valenzuela as the premise of that year’s 13 Artists exhibition. The late Mr. Elizalde, who reviewed the show, singled out my installation among the other works and mentioned something like ‘the artist not being able to deliver his intention’ or “I didn’t quite understand how to treat ‘space,” adding a final commentary that “a gallery is not for pygmies.” A few weeks later, after his critical review came out, he opened his solo show in one of the cramped galleries in Megamall. The uneven installation of his pieces, as judgment call, was what I think, he meant by “managing the space right.” I approached him and introduced myself and as his caterer for that evening. He anxiously stared at me for a moment, smiled briefly and then at some awkward point after the brief exchange, avoided each other for the rest of the evening. Fortunately or unfortunately, I never had a chance to have a conversation with him regarding my concept and how I managed the space in mounting the installation.

Llamar o Tocar a La Puerta (2002)

Do you still get reviewed these days?

I’ve stopped checking if I still get reviewed these days (laughs). Maybe because I think that art reviews nowadays are reserved for auction princes and princesses. However, in reference to reviews from previous exhibitions, I admire the way Dr. Patrick Flores and Ms. Alice Guillermo talked and wrote about the context of my works. No matter how cryptic my messages may be at times, they can see through the visual metaphors of my complex pictorial compositions.

The Carnival Queen (2002)

Do you think that the press is important to your practice?

In some ways, yes. I’m talking about critique and assessment here and not just the usual press releases. It gives me a different viewpoint on how people see and respond to my work and processes since the art of provocation is very important to me. Really now, I want to make my audience think and not just see.

Odi et Amo, Performance Installation, (2001)

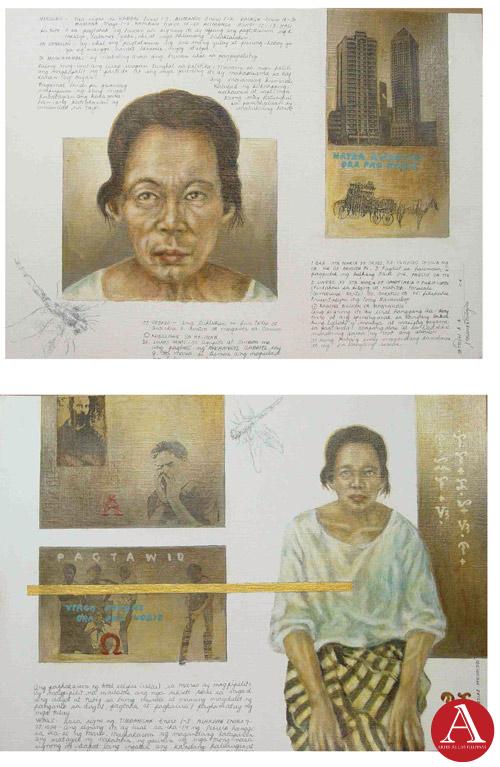

Natividad Fajardo, his grandmother

Tocador

Life & Leisure (2001)

I understand that your maternal grandmother, Natividad Fajardo, was the first artist in your family. In what way did she influence you?

I only saw two of her landscape paintings done in the Amorsolo style in an aunt’s house. She was a student of St. Scholastica’s College. I’m not sure the school has a Fine Arts program at the time. It could have been an affiliate school in the arts. What I admire most in her was her exquisite taste. She was a class of her own as she turned everything into artistically appealing creations from food presentation to table settings to interior decorating and other creative stuff. She also helped me and my siblings with our art school projects. She also allowed us to play with various art materials and having squeezed all the creative juices out of us kids and turned the experience into something like an exercise in solving visual problems at an early age. Di ako masyadong dumaan sa coloring book, my grandmother would encourage us kids to create our own visual narratives, gupit-gupit, drawing-drawing at dikit-dikit, tapos pag-uusapan naming yung process. So may visual translations yung storytelling. Masaya! I also learned a lot of old school aesthetics and decorum from her.

My Lola’s influence was reflected in my installation/performance, Odi et Amo that I did for a Boston Gallery trilogy exhibition of Slash/Art, Tuhog (2001) with Karen Ocampo Flores and Salvador Joel Alonday where I appropriated her old tocador and Astoria’s clock, interfering with them for an installation piece. Natividad at 14 and her Tocador were also my homage to her. The tocador was like a nonya stand where we hid all our drawings and art materials when we were kids.

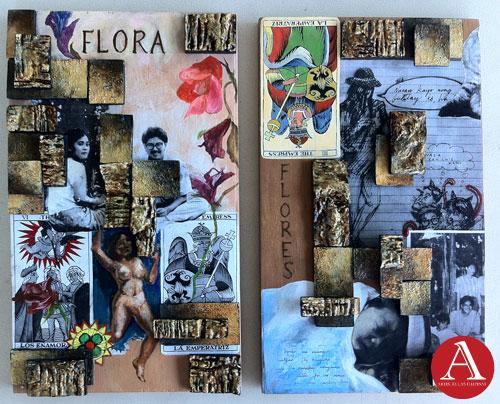

Brenda Fajardo is your aunt. In what way did she influence you?

Brenda Fajardo is my mom’s first cousin. Her father is my Lola’s brother. They came from a brood of fourteen which remained very close-knit, well, until our generation, at least. So we would have these family gatherings. After every festive lunch, kumustahan and kwentuhan, I would go up to her studio. I was fascinated every time I’d see her working in her studio. Tapos, daming kwento about art, history and analytical thinking on current issues. That in a way became an impulsion for my artistic hunt.

Mnemosyne's Progress Report (2003)

You studied in a Catholic private school for elementary and high school. Were you the only visual artist from your batch?

There were many creative kids in the block. Sa Visual Arts, I had a classmate who was the grandson of an art shop owner in Mabini. His name is Ronaldo Gonzales. But they didn’t pursue artistic careers. We would frequent his lolo’s place for a while, daming Mabini paintings. Kasabay yata ni Peck Piñon era yun, late 1970s to early 1980s. Renato Lucas, the renowned cellist was also a high school batchmate, a great guy!

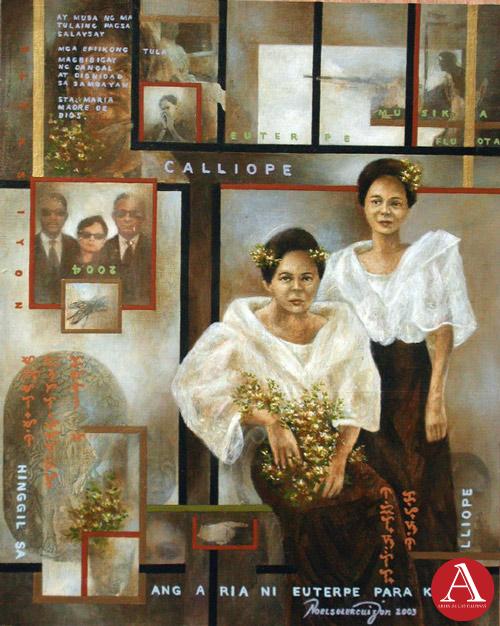

On Euterpe's Aria for Calliope (2003)

You also own a catering business.

I don’t do catering anymore. Catering for me at the time was like curating an exhibition or doing an installation piece. My catering partners collaborated a lot with each other in the kitchen during the 1990s. We use to cater to artists’ receptions in gallery openings and events in various art centers. It used to be exciting especially the part where you discuss about echoing the exhibition theme in table settings or how the food will be presented and all those arrangements that will resonate the premise of the exhibit. When NHK featured me and my works for the 4thAsian Art Show in 1994, together with Elmer Borlongan, they took a video of me arranging the table in one event at Megamall with the assumption that I was finishing an installation piece (laughs). I enjoyed having done the black & white theme wedding reception of Eileen Legaspi and Chitz Ramirez where the entrées were installed as sculptural pieces atop pedestals with make-shift ponds in an appropriated indoor garden. Their wedding was an art event!

Pre-departure Perspective Section B-B (2004)

Pre-departure Iconography (2004)

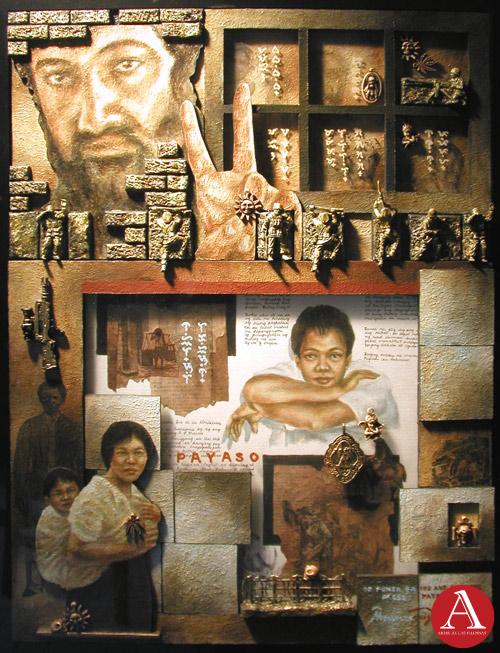

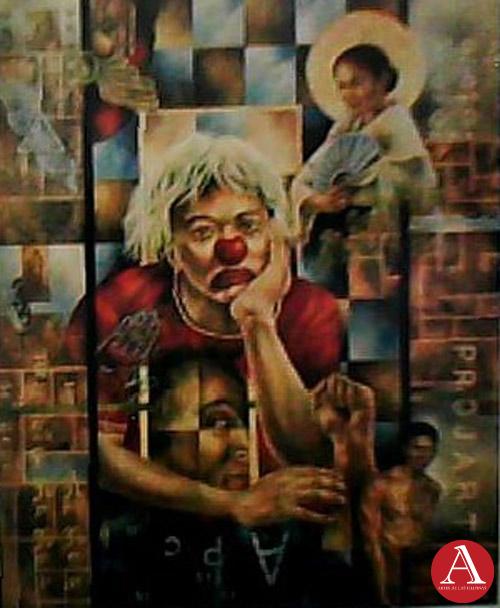

Of Power Grids and Healing Pages- Payaso (2004)

Let’s go back to your art. What new trends have emerged in your art in the last five years?

Having been exposed to contemporary art practice abroad in the 1990s strengthened my adherence to a more nationalistic content in my works or putting a particular universal issue in the Pinoy cultural context. What I’ve notice as a new development in my work, through years of experience is how I would shift gears from one medium to another. I would translate my vision or idea from an originally intended painting or assemblage to social installations or performance art, framing them in new modes of artistic expression to achieve a more effective way of visually communicating a concept.

How did you come up with the idea of interactive assemblage? What was the first work you did? Who were the figures that you put in the party?

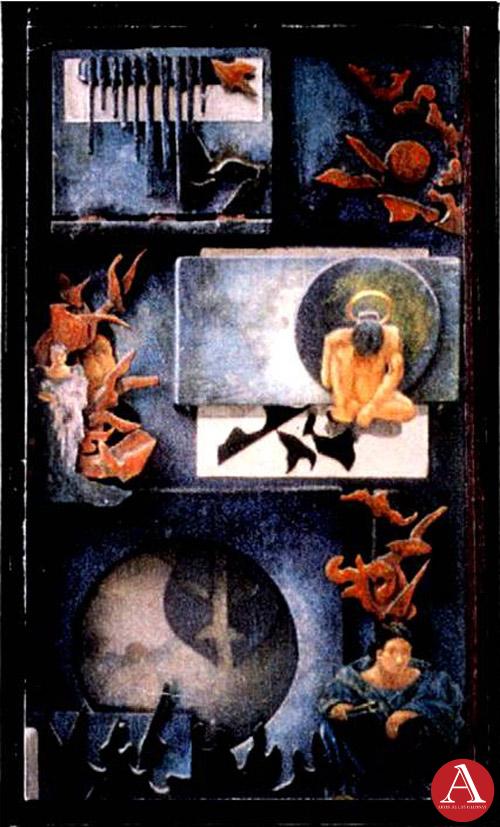

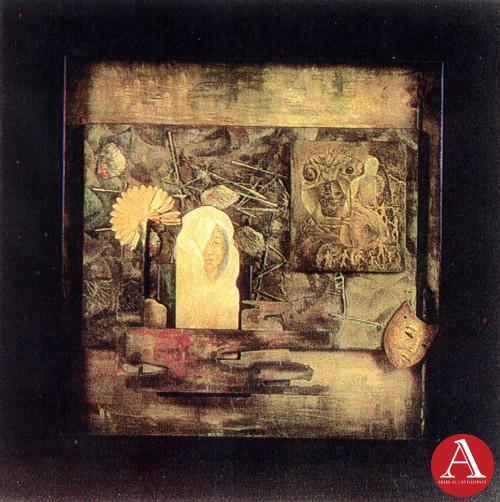

The first assemblage I did was Hanggang sa Muling Pagpanaw, a work from the collection of my undergrad thesis. It was also my entry for the Metrobank Art Competition which won an honorable mention award in 1987. The popularity of surreal themes during that time provoked me to do this piece. What I wanted to do then was to contextualize this theme in a Pinoy manner using images that will deliberately represent a cryptic relationship between reincarnation and our colonial past. The piece was an assessment of reincarnation as a concept enthused during my Ananda Marga days. Posited here was the primary concern to map the response of the audience to an esoteric subject while defining the medium and message within a pictorial configuration of an interactive piece. In completing the work, I utilized various materials such as mirrors to denote infinity, multi-levels of cabinets and platforms to denote openings or doors and the idea of interior/exterior, cut-out wooden figures and found objects to suggest movement that alluded to a multi-dimensional space in a way that I would have interpreted a topic like reincarnation and utilized it as a visual metaphor.

Ipinagbiling Kahapon (1991)

What I would consider as my first successful interactive work was Ipinagbiling Kahapon, a work, which together with Roberto Feleo’s sculpture, garnered honorable mention awards in the 2nd Biennial Exhibition of Arts in Makurazaki, Nanmeikan Museum, Makurazaki, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan in 1991. The artwork was conceptualize in the aftermath of the EDSA People Power Revolution which created a great impact to our generation. It was a synergy of various explorations in our Advance Visual Studies class and other experimentations on visual representation in a range of styles and approaches. My idea was to appropriate Aurelio Tolentino’s Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas, reenacting its stage-like quality as a visual metaphor for that obscure uncertainty exuded after winning a long battle. I wanted to portray the euphoria of the moment by using Inang Bayan in three phases, individually signifying each figure in different configurations. The work took several stages which I started in 1986. I’ve shelved it off for a while then completed only during the first quarter of 1991.

The Limits of a Mea Culpa (2005)

Of Snow Days and Smoking Buddies (2005)

Terpsichore's Centennial Dance (2005)

You’ve resurrected several known and unknown figures in the past with your interactive assemblages. Can you cite specific figures and why you think those figures are relevant to the public?

In my early narratives, I situated personalities, anonymous and iconic figures alike from the past with the intention of connecting parallel events and settings from history to contemporary situations. The audience are informed about how these characters played in history; the likes of Andres Bonifacio, Macario Sakay and even mythical figures like Bernardo Carpio and Hermano Pule, among others . How their stories are contextualized in a new light creates fresh perspectives and interpretations.

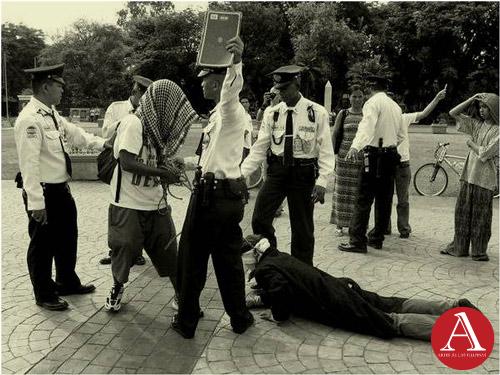

Markadong Bayani. Performance with Crisanto de Leon --- TUPADA Performance Art Festival, Kanlungan ng Sining, Rizal Park (2004)

What was the first act you did?

Markadong Bayani (2004) was my first public engagement with performance art in Manila although I’ve tried my hand at action art before collaborating with other artist-in residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito back in 1998. Markadong Bayani was executed for the Tupada Revolt, a performance arts event mounted at the Kanlungan ng Sining in Rizal Park. It was in collaboration with Crisanto de Leon, another TutoK artist, who took the role of an executioner. Reenacting the execution of Jose Rizal right in front of his monument – we appropriated the idea of Christ falling three times when he carried his cross. This visual appropriation represented the parallel idea of the three-fold principle of thinking, feeling and willing as an effective way of addressing current issues in our society.

Suspecting that the performance might create a commotion, the parks administration tried to stop us in the midst of a crowd cheering in support of our act. We delivered the Markadong Bayani piece despite the consternation of the aggressive guards who were determined to put a halt to the action. The intervention was unexpected but it gave another meaning to the performance.

Markadong Birhen, Performance, TutoK Covergence (2007)

Tutok Soena, 2009, Manila Contemporary, Makati

Tutok Soena, Manila Contemporary, Makati (2009)

Music Video artist Glock 9 Balita (2009)

Music Video artist Glock 9 Balita (2009)

Convergere, Divergentia, Performance (2013)

Convergere, Divergentia, Performance (2013)

InViolate,Collaborative Work with Karen Ocampo Flores (2016)

Paskong Paksiw, Action Performance, Rage Against the Killings, Philippine Women’s University SFAD Gallery (2016)

Paskong Paksiw, Action Performance, Rage Against the Killings, Philippine Women’s University SFAD Gallery, (2016)

Perspektiba ng mga Musa (2016)

Alternative Translations, Performance That Escalated Quickly Exhibition Opening at Sigwada Gallery (Para Site Projects) (2016)

Remembering Yolanda (2017)

Pak Ganern Performance, STALLS at the Hub, 98B Art Laboratory, (2017)

Pak Ganern Performance, STALLS at the Hub, 98B Art Laboratory, (2017)

How does performance art amplify your wall-bound works?

Performance art gives me an opening – a possibility of envisioning my work in dynamic motion. I do not “act” or "entertain" when I do performance art. I “frame” visual concepts to ascertain object, time and space concerns that follow compositional structures similar to how I would treat the visual elements in a pictorial plane. Exploring performance art as a medium serves to expand on the interactive model of my early works as well as define the symbiotic relationship between the message and motivation of all my other works.

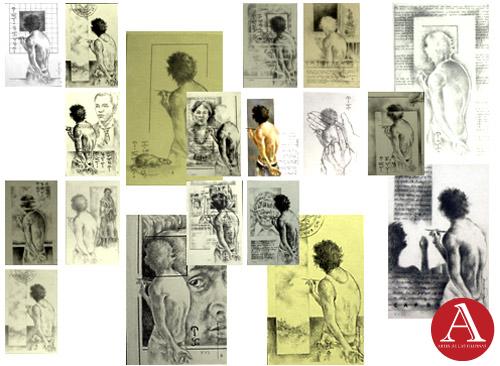

In Transit (100 Drawings), Nineveh Art Space, Sta. Cruz, Laguna, (2005)

In Transit (100 Drawings), Nineveh Art Space, Sta. Cruz, Laguna (2005)

How do you frame your art pieces?

The structure became an imperative consideration when I delved on assemblage works. I’ve certainly applied some knowledge learned in my short stint as an Architecture student. Ironic in a way, I left Architecture not because I didn’t like Math but because I hated mechanical drawing at that time. When I started doing my interactive assemblages, everything became structured that I sometimes have to allow room for spontaneity. There was a need to translate my visual narratives from a pictorial plane to a more complex composition.

Of Carnival Queens and Muses (2006)

Post-Colonial Apocrypha (2006)

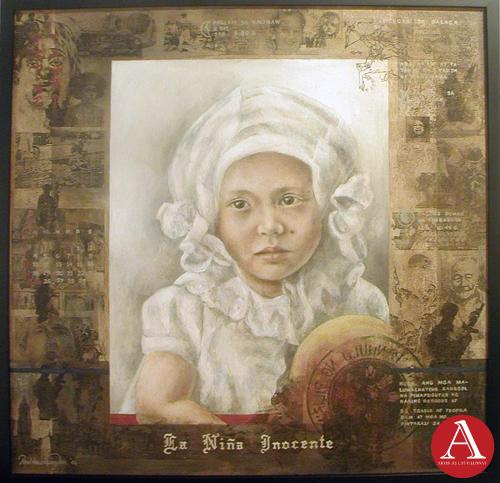

Niñas Inocentes (2006)

You underwent angioplasty in 2010. Did that hiccup in your physical health change you and your art?

It’s been seven years since my heart attack and angioplasty. During the first years after that incident, I became more introspective with my artistic intentions, processes and direction. I wasn’t able to do a lot of artworks though for a long period of time and resorted, as an alternative, to go full-time teaching in the university. For some reason, the mentoring experience gave me a new worldview on the possibilities of fabricating a more holistic learning structure I never had in art school. It also gave me a new way of seeing the diverse creative processes through the lens of my millennial students.

Pledge, SFAD Week (2014)

"Sentido Komon" Exhibition Opening, NCCA with Professor Felipe de Leon Jr., NCCA Chair,

Vanessa Tanco, PWU COO and Mutya Teodoro-Sambile, Program Coordinator for Interior Design

How did you get started with your teaching career?

I started with art education by giving workshops and creating “informal” curricula for art workshops at Escuela sa Museo of the Ayla Museum in 1995. I taught Basic and Advance Drawing, Painting and kiddie workshops for two years and recommended artist-colleagues to join the team and a pool of workshop facilitators. In 2006, I was invited by the director of the School of Multimedia Arts of the Asia Pacific College to be the visiting professor for PROJART, an exhibition class for the graduating students of ABMA. Karen Ocampo Flores was assigned to handle the other exhibiting classes there in 2010. Likewise in 2010, I joined the faculty roster of the Philippine Women’s University School of Fine Arts and Design through the invitation of the then dean, Josephine Turalba. After a year, I was assigned to be the program coordinator of Painting/ Studio Arts until 2016. I also became the curator of the newly opened School of Fine Arts and Design Studio gallery which caters to its faculty, students and alumni from 2011 to 2015. Karen Ocampo Flores assumed the position of its gallery curator after that year until the present. Since then, I've been teaching Foundation and Intermediate courses in Fine Arts, namely, Visual Perception, Visual Studies, Gallery Management, Drawing, Painting, Art History and Art Theory classes.

ProjArt (2009)

Do you ever get creatively blocked? If so, how do you pull yourself out of a lazy or repetitive mode?

Patuloy ang learning process sa art especially when I started teaching. I’ve learned so much from the fresh blood, not so much in terms of form but more on perspectives: how they view life in the contemporary sense, millennial sense (laughs). In a way, that helped me explore fresh idioms of expression. I was also able to process a lot from my travels and exposure through artist residencies especially the one at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Saualito. Having been exposed to other media and disciplines helped me in re-defining my artistic values. To deal with redundancy and major creative blocks, I divert my attention and interest to other activities. I try to experiment on other visual approaches. I also cook a lot (laughs). And of course, I read and orient myself with current trends and punto de vistas.

A Levelling of Perspectives (2010)

Intimate Posturings (2010)

Do you throw away or repurpose your artworks?

There are instances where I re-structure some of my works after years of having done them or continue unfinished works and create totally different pieces out of the originals. Hindi lang nga lahat na-document. How I wish na-document ko yung transitions.

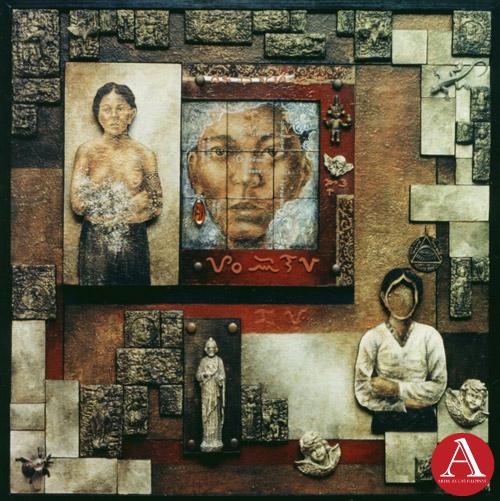

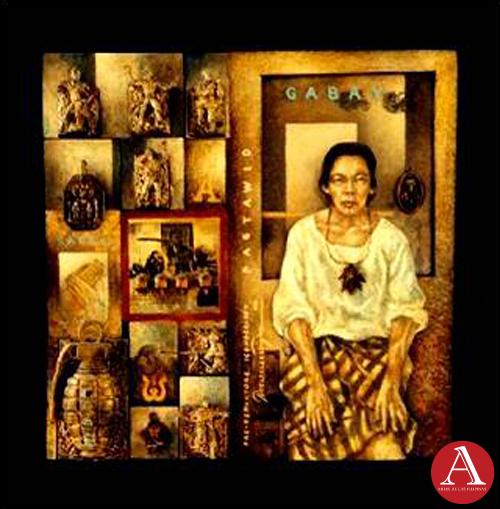

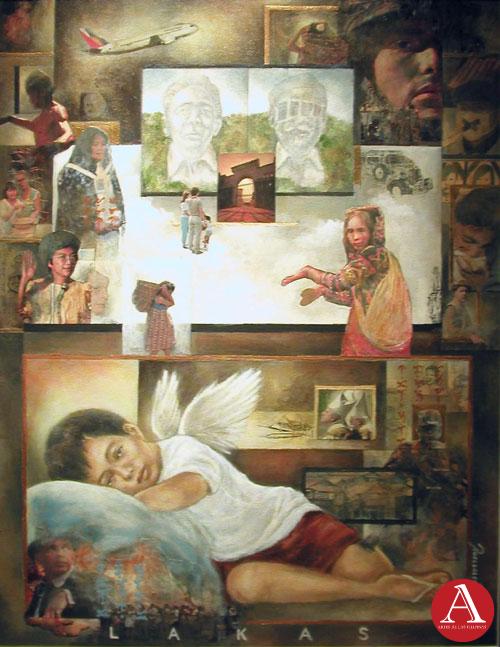

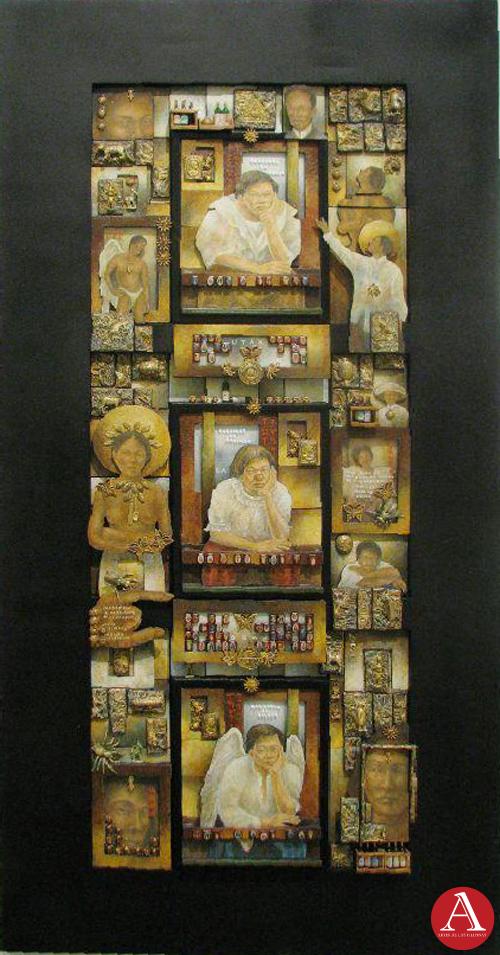

Repaso ng Tres Personas (2011)

What was the most challenging artwork you’ve accomplished?

I’m not a natural (laughs) so halos lahat challenging. I treat almost all of them as major pieces. Tedious kasi yung process para sa isang obsessive compulsive.

Diskurso ni Urbana at Feliza, work in progress, (2012)

Diskurso ni Urbana at Feliza (2012)

Do you treat your art-making like a job?

I was more romantic when I was younger, iba ang ART. Noble obligation (laughs)! But I eventually come to terms with myself and treated it like any other undertaking! Naniniwala kasi ako na pag pinagbuti mo yung ginagawa mo, yun na yun! Either tubero ka or karpentero ka, financial executive or cultural worker. Pag pinaghusay mo craft mo, nawawala na yung hierarchy. It becomes like any other job!

PWU SFAD Artist-in-residence (2013)

What’s the greatest creative high you experience in making art?

The greatest creative high is when you’re able to resolve visual problems encountered in production and when you get to meet visual accidents that help you in communicating your intentions. Picture a trance-like experience – para kang napapa-atras sa work mo in the tune of – ano na nga ba yung background music sa Toulouse Lautrec film? – na para kang hinihigop nung artwork mo. You want to be engulfed by the piece. Kahit hindi ka naman drugged (laughs). Ecstatic lang yung feeling!

Talk Asia Interview with Lorraine Hann and Santiago Bose with Soler Cuizon, Hong Kong

Noel Soler Cuizon with Monsoon Memories, Tao-Tao Project of the ACC, FAME, SMX, Manila (2012)

Can you point out a moment in your career that was significant to you artistically?

Engagement with other artists and curators that have enriched my artistic endeavors, exhibits, Biennales, artist residencies, konting award-award (laughs) or when you see yourself in a CNBC and NHK TV coverage. It makes you think and assess your direction as a practitioner. Questions like, saan ko na ba dadalhin ito? What I’ve learned though through the years is huwag kang maniwala sa sarili mong press release (chuckles). Only you can decide kung nasaan ka na at kung saan ka pupunta in your creative journey.

Transient Resolve, Installation, Impetus 3 Constructs of Absence (2014)

Re-Territorialities, Collaboration with PWU Faculty (2015)

How about a specific moment in your career that you are embarrassed to have done?

Nothing embarrasses me (chuckles). Parang wala naman akong pinagsisihan sa mga nagawa kong art. May mga awkward incidents lang like when people mistook me for another person or when they see that Nuki is not the same person as Noel Soler Cuizon. Napakaraming ganoong incidente before! I guess my reputation precedes me (chuckles). “Magaling yung si Noel Soler Cuizon ah, gusto ko yung work niya, kilala mo siya!” Sabi ko, “Hindi masyado! Kung minsan ka-meeting mo na, tatanong pa kung nasaan daw si Noel Cuizon… sabi ko ako din yun, Hindi si Nuki ka, eh, ikaw din ba si Noel Soler Cuizon (laughs)! Mahirap seriosohin ang sarili (laughs)!

Retablo para Los D-Tards y Desamparecidos, in progress, (2016)

What can we expect from you in the next five years? Any projects you are working on?

More art production, collaborations and curating a crossover group show at the Cultural Center of the Philippines Main Gallery. My dream project in the next five years would be to collaborate with artists coming from diverse influences and persuasions set in the context of contemporary art practice and education – co-curating a trans-media exhibition that will focus mainly on the educational, formal or informal, component of different artistic disciplines. This will highlight significant contributions from creative practitioners that would address issues and concerns about forged relationships between art education and art practice – articulated through the different lenses of artists in their assigned medium, message and motivation.

Recent Articles

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISM

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISMJUNE 2024 – Federico Sievert was known for his art steeped in social commentary. This concern runs through a body of work that depicts with dignity the burdens of society to...

.png) FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO

FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISOMarch 2024 - Alexander Narciso is a Philosophy graduate from the Ateneo de Manila University, a master’s degree holder in Industry Economics from the Center for Research and...

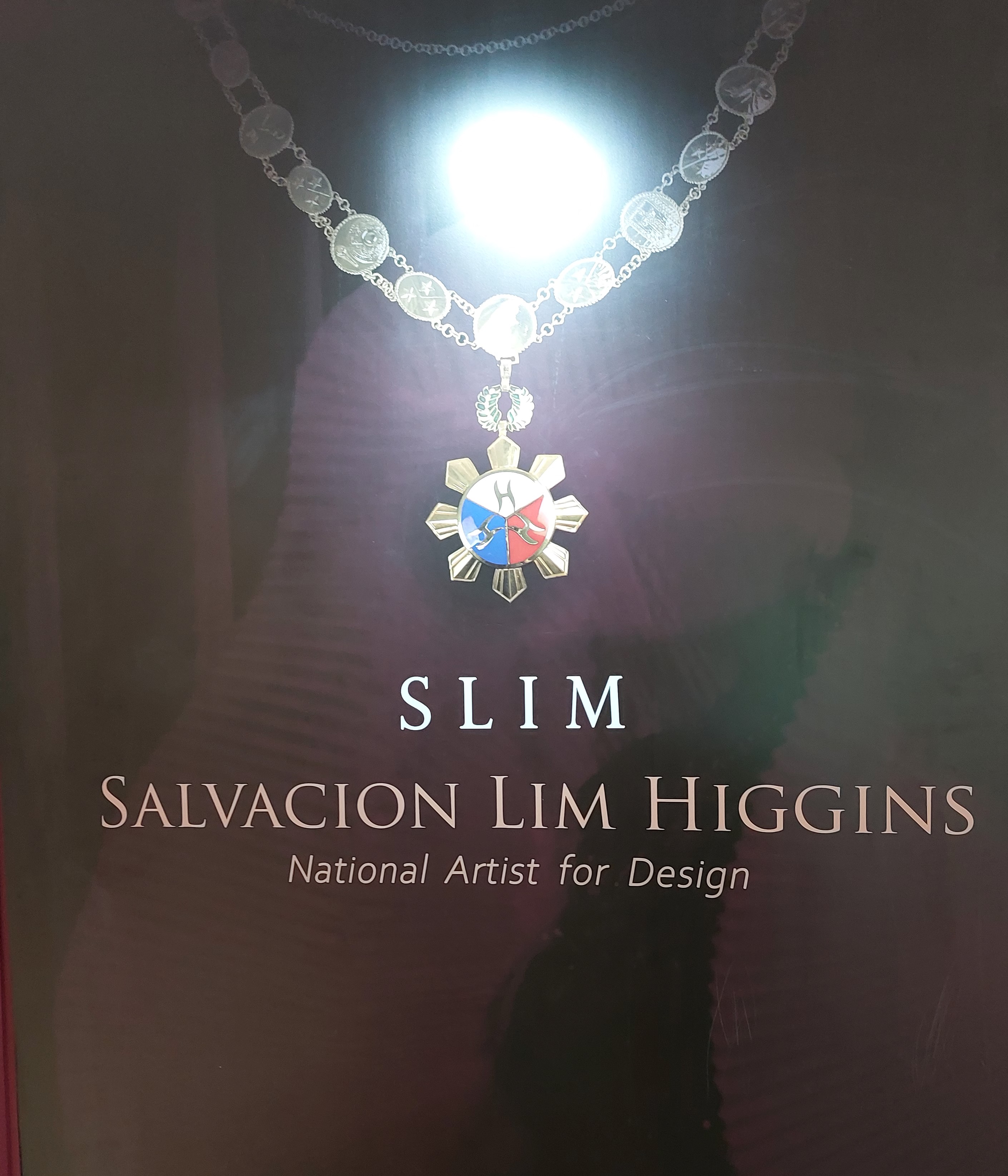

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim HigginsSeptember 2022 – The fashion exhibition of Salvacion Lim Higgins hogged the headline once again when a part of her body of work was presented to the general public. The display...

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All TimeOne of the emblematic komiks writers in the Philippines, Jose Zabala Santos contributed to the success of the Golden Age of Philippine Komiks alongside his friends...

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

The Philippine Art Book (First of Two Volumes) - Book Release April 2022 -- Artes de las Filipinas welcomed the year 2022 with its latest publication, The Philippine Art Book, a two-volume sourcebook of Filipino artists. The...

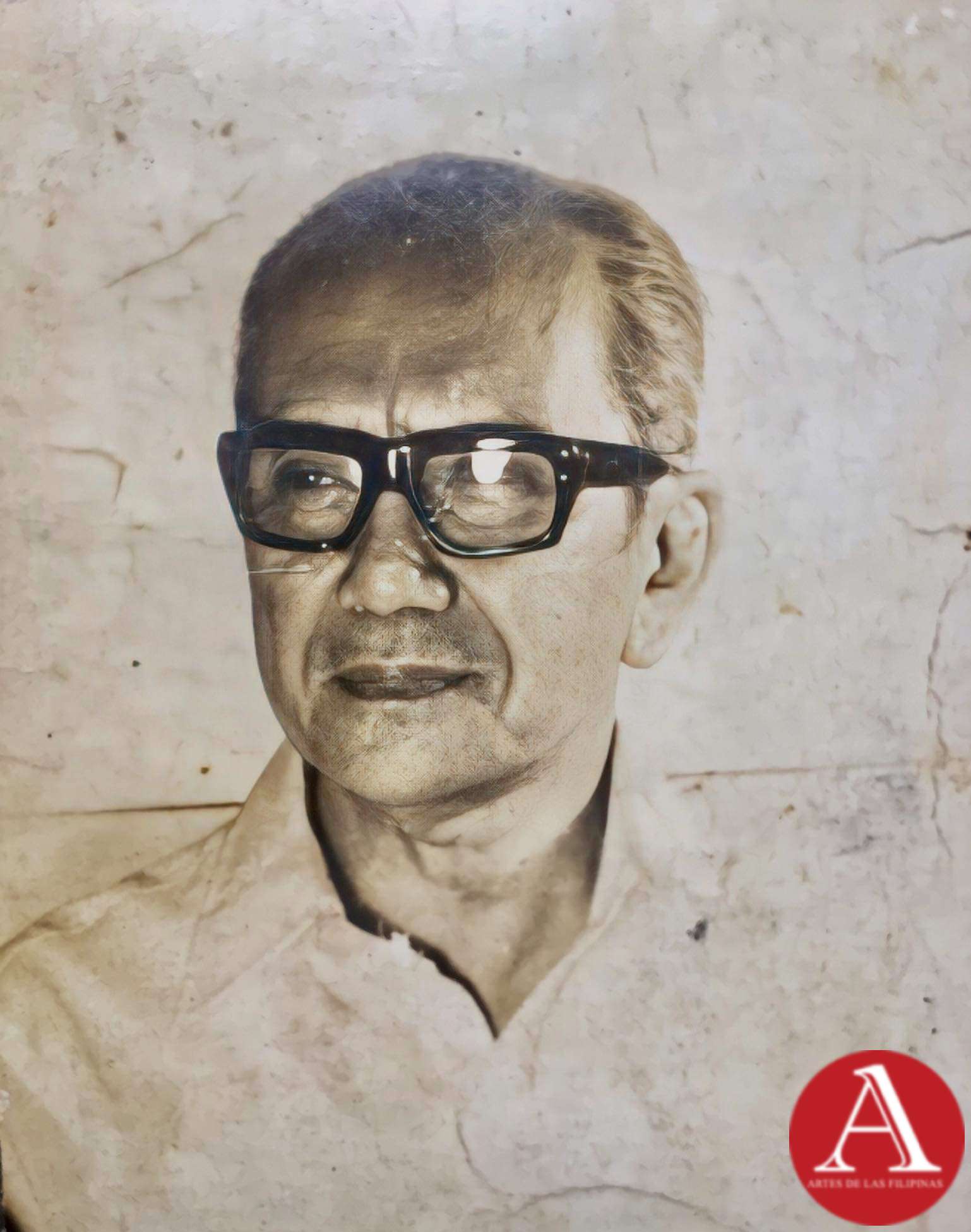

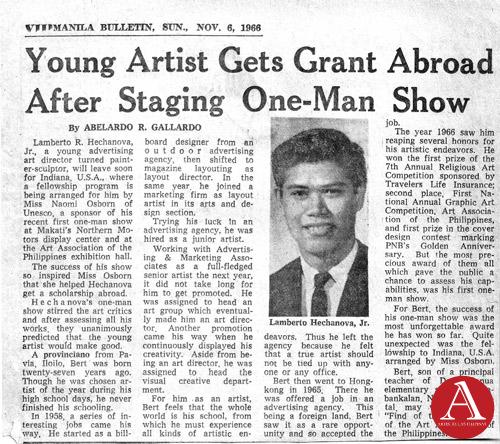

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and FoundJune 2018-- A flurry of renewed interest was directed towards the works of Lamberto Hechanova who was reputed as an incubator of modernist painting and sculpture in the 1960s. His...

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise CemeteryApril-May 2018--The Pere Lachaise Cemetery in the 20th arrondissement in Paris, France was opened on May 21, 1804 and was named after Père François de la Chaise (1624...

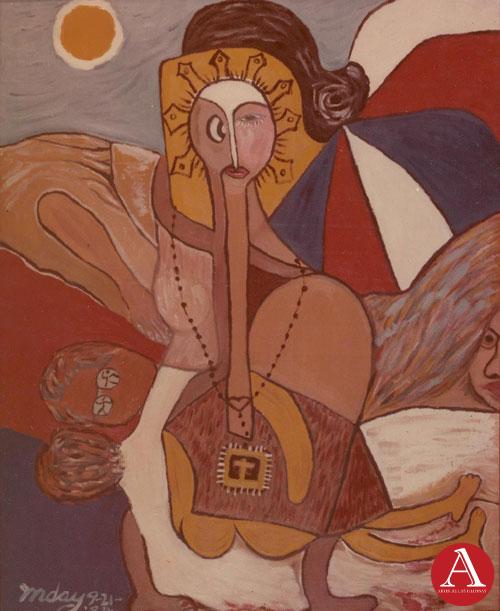

Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday

Inday Cadapan: The Modern IndayOctober-November-December 2017--In 1979, Inday Cadapan was forty years old when she set out to find a visual structure that would allow her to voice out her opinion against poverty...

Dex Fernandez As He Likes It

Dex Fernandez As He Likes ItAugust-September 2017 -- Dex Fernandez began his art career in 2007, painting a repertoire of phantasmagoric images inhabited by angry mountains, robots with a diminutive sidekick,...