The (Stifling) Spaces of Femininity in the Philippine Art World: A Book Review on Flaudette May Datuin’s Home Body Memory: Filipina Artist in the Visual Arts, 19th Century to Present

by: Molly Anne Velasco

August 2012–Home Body Memory: Filipina Artists in the Visual Arts, 19th Century to Present by Flaudette May Datuin, Ph.D. is a recount of the history of Filipina artist from during the 19th Century until the present time on which the book was written and published in early 2000s. Datuin, an Associate Professor in the Art Studies Department of the University of the Philippines, is an advocate of feminism in the Philippines. She has curated and organized various exhibitions and forums on women artists in the Philippines and across Southeast Asia. In the text written by Professor Patrick Flores for the book, he refers to the book as a charting of the “itinerary of the history of the Filipino artists in the visual arts…from the abode of the ‘feminine’, a sense of belonging to a tradition of norms governing women in a social milieu”(Flores xi).

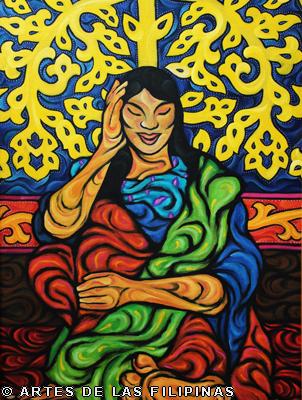

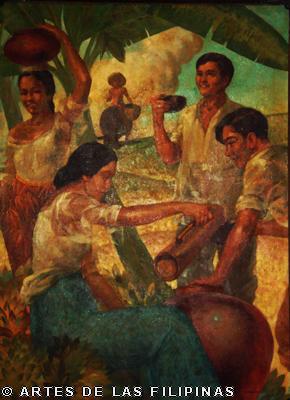

Datuin begins with the acceptance of Paz Paterno in the Academia de Dibujo y Pintura during the 19th century, the emergence of women modernists during the 20th century and eventually the establishment of groups which are sympathetic to making women more visible in different fields in the current era (Kasibulan and Gabriella among a few). She doesn’t simply narrate the history in a chronological manner, she refers to her process as a “re-telling a compensatory history that women have been making art since the 19th century and continue to do so till the present”(Datuin 68). She also singles out certain artists whose works and insights she deem essential to her book; focusing more on the visual arts particularly in painting, sculpture, installation and performance art and how they portray women, canonical or otherwise, in their works. These images include the woman with child, depiction of women in their “spaces” in their homes and portrayal of women as goddesses, nymphs, virgins, vamps, victims, etc.

Datuin also discusses the often disparaged activity of tsismis or as Datuin calls it, usapang babae among sewing circles s a seemingly trivial yet may have posed as an instigator for the early feminists to clamor for equal rights during the mid 19th century. The presence of gossip among sewing circles across cultures has often been an activity associated to women with malicious idle minds. These circles represent a space wherein women are free to do and say what they want without the prying, disapproving eyes of men. The presence of such group activities consisting of women sewing is a cross-cultural phenomenon; from the Filipina embroiderers and weavers of traditional cloth, Korean pojagi weavers, American quilt-makers to the contemporary artists such as Alma “Urduja” Quinto. Quinto’s use of the act of sewing a quilt while sharing stories and experiences provided a medium for the participants to air their trepidations through the art form as individuals subjugated in the spaces of their own homes.

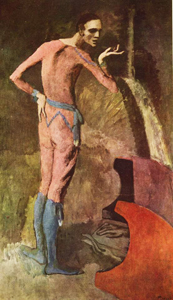

It is often said that, “In order to be successful, a woman artist had to produce masculine art.” (Feminism in Art) . In order to be accepted, women have to take the form of men, wear their “eyes” and become as what Griselda Pollock calls “intellectual transvestites” (Pollock). However, even women artists who have indulged in said “masculine art” such as painting and sculpture are more often than not overlooked and sometimes excluded by dealers and art critics. In a personal interview of Karen Flores conducted by the author, Flores’ art dealer herself commented that her being a woman would, “Very likely you’re not going to make it” (Datuin 147, 231).Datuin also throws in the question, “Is there such a thing as Women’s art?”While the medium women are usually associated with are subject to discrimination (e.g. “Low” art, crafts, hobbies such as knitting, quit-making, weaving, etc.), even those who take the gaze of a male and portray art in their medium and form, women artists still do not enjoy the same treatment as male artists do. Datuin also asserts, that while most women, especially feminist artists consciously depict feminine and feminist style, themes and contexts; some female artists choose not to be identified as a woman or refuse the label “feminists.”

In addition, Datuin quotes Pollock, telling us that feminist analysis “must be its own perpetual provocation and auto-criticism” (292); that women are not excluded from history, politics and race.She mentions that further discourse should also be done to other art forms such as photography, dance, theater, mass media, etc. as well as more indepth studies in performance art, lesbian art and themes as well as artists outside Manila.She believes that women arists’ resistence to the canon which subjugates them will someday “move on from an aesthetic of oppression and victimization, towards one of transcendence and liberation” (289).

Datuin locates herself within contemporary Philippine Feminism which hinges on alliances built on class and anti-racist struggles (Datuin 15). She identifies her feminist beliefs with the struggles of the early feminists movements who critize the images of women archetypes created in the male-gaze, the liberal feminists who “subscribe to the framework of parity or ‘equal rights’” (17), and the radical feminists who advocate seperatism towards all men in order to escape patriarchy. She also locates herself with the “Third world” feminists whose beliefs are closer and more relevant to the circumstances of Filipina women. Thus, Datuin associates her feminst stand to the mainstream western discourse and an “elsewhere” as “complexly part of the fabric of historical discourses, institutions and practices” (Datuin quoting Pollock 16); forming dialectical acord with post-colonial and materialist feminism.

The book, Home Body Memory: Filipina Artists in the Visual Arts, 19th Century to Present bind the words Home, Body and Memory in the further understanding of the history of Philippine art. She defines the Body literally as a physical attribute of a person and as a site of identity and function (Datuin 15); the Home as a physical structure, nuclear community, an institution and the site of the body’s negotiations (Ibid) and the memory as an embodied feeling, experience, thought and action (Ibid).Home, Body and Memory in the various artworks present in the book therefore serve as a sign that dennotes certain world views that describe the views of the female as a subject and a creator in the Philippine context.

For example, Datuin highlights the importance of usapang babae and Women’s art groups such as Kasibulan as a space where women are “on their own”separate from men. This is not to say that the complete absence of men would solve the problem of gender inequality in the Artworld. Rather, this temporary retreat can act as a support system not only to discuss friviolities and domesticity conflicts but also strengthen the newly establish paradigms, turning “in perpetual auto-critique, to find our frames, methods and language”(Datuin 234)

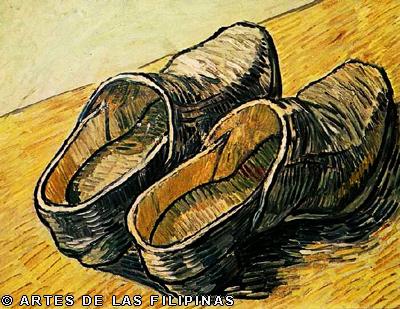

Datuin also criticizes the canon, the imposed vertical hierarchy of art, classifying different art forms according to formalist academic traditions but also the blatant biases between “high” and “low” art. Said “low” non-academic art are defined as mere crafts. Historically, the arts that women are traditionally associated with such as weaving, knitting, quilt making are seen more as mere crafts, or products of a hobby to keep a homemaker’s mind busy. Datuin mentions a number of visual artists who have presented a myriad of media different from the stereotypical materials used in creating art. In fact, she also brings up a certain student from UP College of Fine Arts who took the risk of presenting cross stitch work as his undergraduate thesis. He was met with apprehension by his own professors and peers. Even family members were questioning his choice of medium and associated it to his sexuality; connoting that stitching was for women and he must be turning homosexual. There is a noticeable marginalizing attitude toward the selected media of the student; it was as if the feminine and homosexual were something of lesser ranking as compared to the masculine. Again, this is rooted to the hierarchical biases of the Artworld towards not only the art created by women but as well as the “feminine” mode of expression.

There is a brief mention of female homosexual artists in the book. However, the author admits to being condensed and lacking perhaps due to theoretical, time and logistical constraints among other things. She suggests that further studies on female homosexual artists should be done in the future.

Datuin also presents her arguments in an intersubjective structure; her framework is largely drawn from various feminist viewpoints and further instituted by her interactions with women artists.This analysis believes that theory must be established through concepts which share a similar experience.However, the danger of exposing their personal lives is that one may contest to the biases these women contribute to the seemingly perception of women as constant “victims” in a patriarchal society.Some artists also state that many of their works are in fact, expressions of their discontentment as wives, daughters, and as women in general. There is a perceived one-to-one correspondence to an artist’s work and her life (Datuin 227). In fact, Karen Flores reveals that she is often faced with gossipy questions about her work and life; stating that these inquiries have been reduced to voyeurism (228). Some of the artists in the book such as Francesca Enriquez deny any political intention and content with her artwork (136).Perhaps this is a common belief among artists; that “creativity” is detached from theory. She admits that she does not feel discriminated against because she is a woman (Ibid) yet she admits that her painting of homes stem from the fact that she has personal domestic problems that she was hiding from.While many of these artists derive their subject matter from their personal experiences and themselves, artists like Flores not only paint to represent their “lives and personal self, but also her identification with the collective “we” of community, and racial and ethnic identity” (146).

Similar to Virginia Woolf in her book, A Room of One’s Own, who asked whether language was a distinctly marked by gender (Kolmar, Lexicon of Debates 51),Datuin asks if there is such as thing as “Women’s art?”Many heterosexual artists have refused to call themselves as “women artists”, referring to themselves as simply artists. While the medium women are usually associated with are already subject to discrimination, such as textiles and weaving , the visual arts has a repertoire of methods and materials whose specific nature tend to be highly masculine (Flores, Cracking the Canon, Repositioning the Other: Towards a Reterritorialization of Philippine Visual Arts 59). Datuin was asked by social realist artist Jose Tence Ruiz in a forum, to “tell at first glance, without seeing the name of the artist, if a work is by a woman? How and how not?” (Datuin 243). ‘Women’s art’ therefore are context-driven and context-generating artistic practices and productions by women.

Datuin further explains that even if women may not be consciously working as authors of “women’s art” certain nuances such as their use of space can be identified as feminine. Datuin quotes Pollock: “The spaces of femininity are those from which femininity is lived as a positionality in discourse and social practice… Femininity is both the condition and the effect (245). These difference in spaces found in still life, abstract and social realist artwork are noticed in the way created by women.Datuin describes an oil painting by Lydia Ingle aptly called, Tsismis (1994) as a visual retreat into a world of our own away from the stresses of a dominiant social order (216, emphasis mine). The act of gossiping, though seen as a feminine act of trivial conversation, can also be a source of empowerment for women, re-contexualized as “usapang babae or women’s words”. A language where women can be her own.