A Critical Essay on Constructing the Filipina: A History of Women’s Magazines (1891-2002)

by: Molly Anne T. Velasco

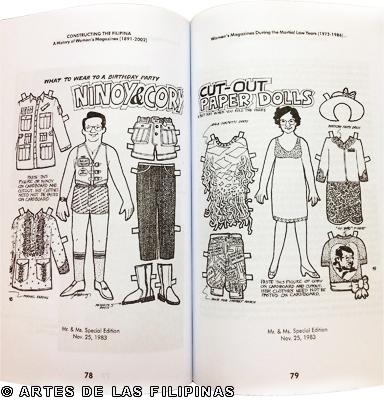

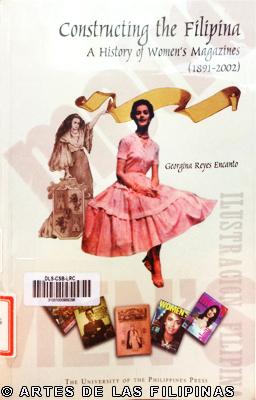

April 2013--Constructing the Filipina: A History of Women’s Magazines from 1891-2002 by Georgina Reyes Encanto is a first attempt to record the history of Women’s magazines in the historical-feminist perspective. The author herself is the former Dean of Mass Communication and a Journalism professor in the University of the Philippines. Her research interests mainly cover Philippine press history, feminism and gender issues in Philippine media and popular culture.

She begins her book with an introduction to the location of Women’s magazines in the lives of everyday Filipina women. Women’s magazines are the most accessible forms of media for women of different social classes. Topics of magazines usually include gossip, fashion, tips for the house and the workplace, horoscopes and relationship advice, all of which are absorbed by many of the readers from cover to cover. The pictures of beautiful scantily clad or fashion forward women who the readers idolize are often found on the covers along with advertisements of products that are supposed to aid women into becoming like the celebrities they adore. Encanto gives specific statistics regarding their circulation well as statistics on which medium and the percentage of the population were actually reading magazines thereby establishing factual evidence on Women’s magazines’ ubiquity. She also states that the study of women’s magazines as an Ideological and/or Repressive State Apparatus is a challenge yet a necessity because of their influences in the ideologies, decisions and world-view of women in the country within the book’s given timeframe. She mentions that while cursory historical accounts have been made by earlier writers, none of them have written in the historical-feminist perspective or have focused on women’s magazines specifically.

The author describes that women’s magazines did not appear until the last quarter of the 19th century. The women writers at that time were of bourgeoisie, ilustrada upbringing who propagated dominant Western, patriarchal and religious ideologies to their readership. The articles in these magazines had women assigned to subordinate, domestic roles; deceiving women by romanticizing their roles as homemakers thus establishing the ideas of the hegemony during that era. Amidst the seemingly progressive articles that promote women’s development, juxtaposing these against repressive, colonial ideologies was very evident with the portrayal of the ideal women as learned and cultured ‘Queens of the Home’ in a patriarchal society. The ideal women exist to serve their husbands and use her knowledge for the proper upbringing of her children. The perception of physical beauty should reflect those of the meztisas and the Caucasians women and their knowledge in the field of science and the arts are downplayed and subject to the machinations of the hegemony. Religion’s monopoly of the governing ideologies during the colonial era as a Repressive State Apparatus further established the roles of women as decorative but learned servants to their husbands, invoking the church and its teachings as the reason to legitimize women’s roles as queens of the home.

The acquisition of the Philippines by the United States provided a sudden shift from the backward, moralistic Spanish hegemon to the modern, libertarian leadership of the Americans. Encanto noted that the Americans propagated the use of their language and imported their books as well as their music, Hollywood movies and other popular forms of entertainment as methods of subjugation to the Filipinos. One magazine, the Filipinas Revista Semanal Ilustrada, aside from publishing articles about sciences, health, personality and literature also covered the activities of feminist organizations and considered the women as a dominant influence in the nuclear family. The magazine’s objectives were to give attention to the rights of women to be recognized as members of the socio-political sphere because of the notion that; Women are the rock on which the value of a nation stands: on her intelligence and ignorance are based the intelligence and ignorance of the citizenry (Encanto 37-38). While these magazines contain progressive material, they were also funded by advertisements of foreign domestic products further established many Filipinos preference towards these over our own products. Nevertheless, aside from light articles that discussed celebrity gossip, tips and home care, many of these publications also featured serious matters here and around the globe such as the feminist movement in the United States and advocated many feminist causes such as Women’s Suffrage, paid maternity leaves and women’s rights in the legal political, social and educational fields. Women’s magazines during the American period then, were venues for the feminist movement to articulate their issues of concern and express their opposition against the patriarchal hierarchy. (Encanto 50)

Newspapers in the post-war years proliferated and included supplements joined the many emerging women’s magazines in propagating and influencing Filipina women. These magazines were patterned after American magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, etc. which contained advertisements that promoted the American lifestyle as an ideal fantasy life for the female readers. Cover photographs of these magazines feature women from the elite and fell under the colonial standards of beauty. There was an obvious lack of articles that dealt with many serious political issues such as discrimination in the work place, rape and other women’s concerns because these were considered “unwholesome” and too “shocking” for these magazines.

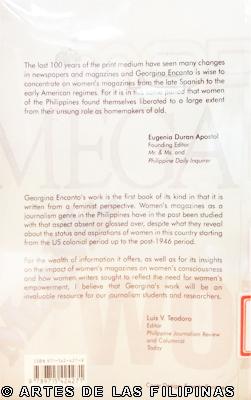

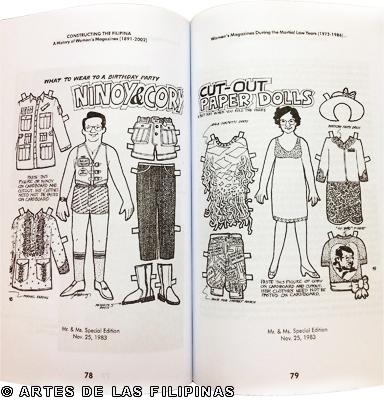

Women’s magazines were practically the only publications allowed to proliferate during the Martial Law years because they weren’t considered a political threat to the government. However, the trend on Women’s magazines changed when editor Eggie Apostol of Mr. and Ms. Magazine decided that she simply could not ignore the political and social turmoil in the country. The media blackout that occurred right after the assassination of Sen. Ninoy Aquino, instigated Apostol to publish supplements that featured serious and light-heart articles that were “subverting the dictator while apparently dishing out innocuous material”. Mr. and Mrs. became a vessel for the people’s voice of discontentment and desire for freedom from the oppressive government and included women in the male-dominate political sphere. Encanto concluded that Mr and Ms. illustrated that popular cultural forms like magazines are hegemonic because while they expressed the dominant ideology, they could actually accommodate elements of resistance” (Encanto 84).

Magazines have become the favourite reading material of women of different ages from different walks of life during the 90s and early 00s. These magazines’ main selling point lies in their fantasy values or a range of fictions that can include, “visual fictions of advertisements, or items on fashion cookery or family and home, which attempts to draw women into the world of the magazine and ultimately a world of consumption” (Encanto quoting Winship 91). Most of the magazines nowadays present a false sense of empowerment to women; for example juxtaposing articles about key issues about women’s self-image with advertisements of products that send subliminal messages to women, highlighting her imperfections. Articles about women’s rights and strength are placed side by side pictures of women in provocative, overtly sexual positions catering primarily to the male-gaze.

The Frankfurt School of Critical Theory has a very pessimistic view of the masses. They believe that the masses unmindfully absorb the principles distributed by the ruling elite. Media, in this context, Women’s magazines, are regarded as being 'locked into the power structure, and consequently as acting largely in tandem with the dominant institutions in society (Chandler quoting Curran). The masses in the Frankfurt School are thus defined by their unwillingness or lack of consciousness to the knowledge that their current ideologies are simply results of the mass media’s influence over them because they divert the attention of the masses from the reality of oppression (Hainsworth).

According to Antonio Gramsci however, the masses do not simple accept the hegemony unconsciously. The hegemony is in constant negotiation with the subjugated groups and the people who negate them to be able establish their place in the hierarchy. Fiske argues that the dominant ideology is “in need of constant re-adjusting to remain dominant... It could be argued that only when consent is created and enforced by the media, that compliance and 'order' can be guaranteed.” (Hainsworth quoting Friske).

The work of disseminating ideology, on the other hand, lies in the two kinds of intellectuals; the organic intellectuals (those who belong to the elite and the working class) and the traditional intellectuals such as philosophers, writers and the prominent religions leaders in a society. Marxist theory emphasizes the importance of social class in relation to both media ownership and audience interpretation of media texts (Chandler). In the book, she quotes Angela Mc Robbie who calls magazines, “the most concentrated and uninterrupted media-scape for the construction of the normative femininity”. Marxists define different classes on the basis of their relation to their means of production; the bourgeoisie class, who are owners of the modes of production in a capitalist society and the non-owners or the working classes. The hegemony in the Philippines consists of many opposing (sometimes acquiescing, forces). The government, the Catholic Church, schools and the media all play vital roles in the development and spreading ideologies to the people. The government and media in particular all play interchanging and related roles in the reproduction and dissemination of dominant ideologies. It is also interesting to note that many of the key players in the government have been and sometimes are, still members of the media. Encanto indicates that the editors of these magazines are highly educated women who may or may not be conscious of their roles as Traditional Intellectuals according to Gramsci, whose roles are to organize and disseminate the new culture which supports the dominant economic system (Encanto quoting Bennett et al).

Encanto discounts the other numerous Marxist feminists framework from her analysis of the history of Philippine Women’s magazines. Instead, Encanto makes use of Althusser’s Ideological state apparatuses and Gramsci’s Theory of Hegemony to explain the evolution of women’s magazines in the Philippines as well as their influences (or lack thereof) in the public sphere. While Althuser’s ISA and Gramsci’s theory of Hegemony do not necessarily reflect the demands of the post-colonial and/or the feminine, Encanto successfully translates these theories to the writing of the history of Women’s magazines. She relates the occupying foreign powers as the hegemons of the state whose ideas are being appropriated by organic and traditional intellectuals. She refers to the female editors and writers of these magazines are Traditional Intellectuals, being products of schools and universities who are autonomous from the hegemony. However, these women should be considered as Organic intellectuals instead because they constantly evolve along with the dominant social group and are tools of these groups to establish their place in the hierarchy.

A case study done on the Content Analysis of the Image of the Filipina in Philippine Society by Esperanza Ramos Reyes showed that many of the women who read Women’s magazines still identified with domestic roles and chose to read articles related to it. On the other hand, another study suggests that Women’s magazines limit the portrayal of women in three distinct stereotypes: as a fanatic, beauty object and a homemaker all of which are not proper representations of women. Presuming that the target readers of such magazines are in fact, the enlightened third-world bourgeoisie, we can safely assume that women’s magazine readers are educated and aware of the individual, social, moral implications of their actions. These women in fact know that not every article and advertisements featured in these publications are based on facts; ergo not as mindless as the Frankfurt School deems them to be. Thus, the success of these magazines lies on sublime subjugation: the act of glamorizing and sugar-coating their misleading ideologies to appeal to their target markets. Magazines are escapist fare and provide a medium where women can “vicariously indulge in the good life through the image alone.” (Encanto quoting Winship 91) and these feelings and desires provide fodder for the commercial interests of women’s magazines.

Another factor to consider in the production and dissemination of ideologies are the owners of said media. Most, if not all, of the owners of these media companies are neo-liberalist men promoting materialistic, capitalist ideologies for their own expedience. Subversive, progressive political beliefs do not sell and therefore are hardly, if not, never written about because of the dominant materialistic and individualistic ideologies that are being propagated by the media. While emphasis on ones self is not necessarily innately evil, extreme individualism and reliance to material wealth diverts a person’s attention away from the matters of society and the state. Sex sells, and sexuality and oppression have always been a successful means of generating income for the individuals who control these companies.

It would also be interesting to add at least a personal recount of individual women who have engorged themselves with these magazines and how their content has actually influenced their lives at home and in society. While the empirical evidence of the vast readership of Women’s magazines is already evidence enough of their ubiquity, interviews of women whose lives have been directly affected by said magazines would further testify to the fact that there are indeed faces to these statistics.

These publications and other media are merely one of the tools used to inject dominant social ideologies into the minds of the masses. The medium of expressions themselves are not the source of the problem, because these magazines have redeemed themselves as tools of disseminating feminist consciousness and became an opposing political force against a repressive government body. It is the misuse of the medium’s ubiquity to subliminally oppress women, establish patriarchal ideologies and that cast women’s magazines into feminist criticism. Ultimately, the challenge for other intellectuals, organic or traditional, is to subvert the oppression by propagating feminist consciousness among women, starting at an early age. Education plays a crucial role in establishing an ideology. Furthermore, feminist consciousness can benefit from these modes of expression to propagate their ideology and counter the dominant oppressive ideas being fed to the masses. At the end of the day, it is up to women themselves to transcend the dominant repressive ideologies and rescue themselves from being the mindless followers of a state apparatus.

REFERENCES

Chandler, Daniel. "Marxist Media Theory." 1995. The indispensable Media & Communication Studies Site. 3 February 2011 <https://aber.ac.uk/media/>.

Encanto, Georgina Reyes. Constructing the Filipina: A History of Women's Magazines (1891-2002). Quezon City: UP Press Printery, 2004.

Hainsworth, Stuart. "Gramsci's hegemony theory and the ideological role of the mass media." 2000. Cultsock: Communication Culture Media . 2 February 2011 <https://cultsock.org/index.php?page=contributions/gramsci.html>.

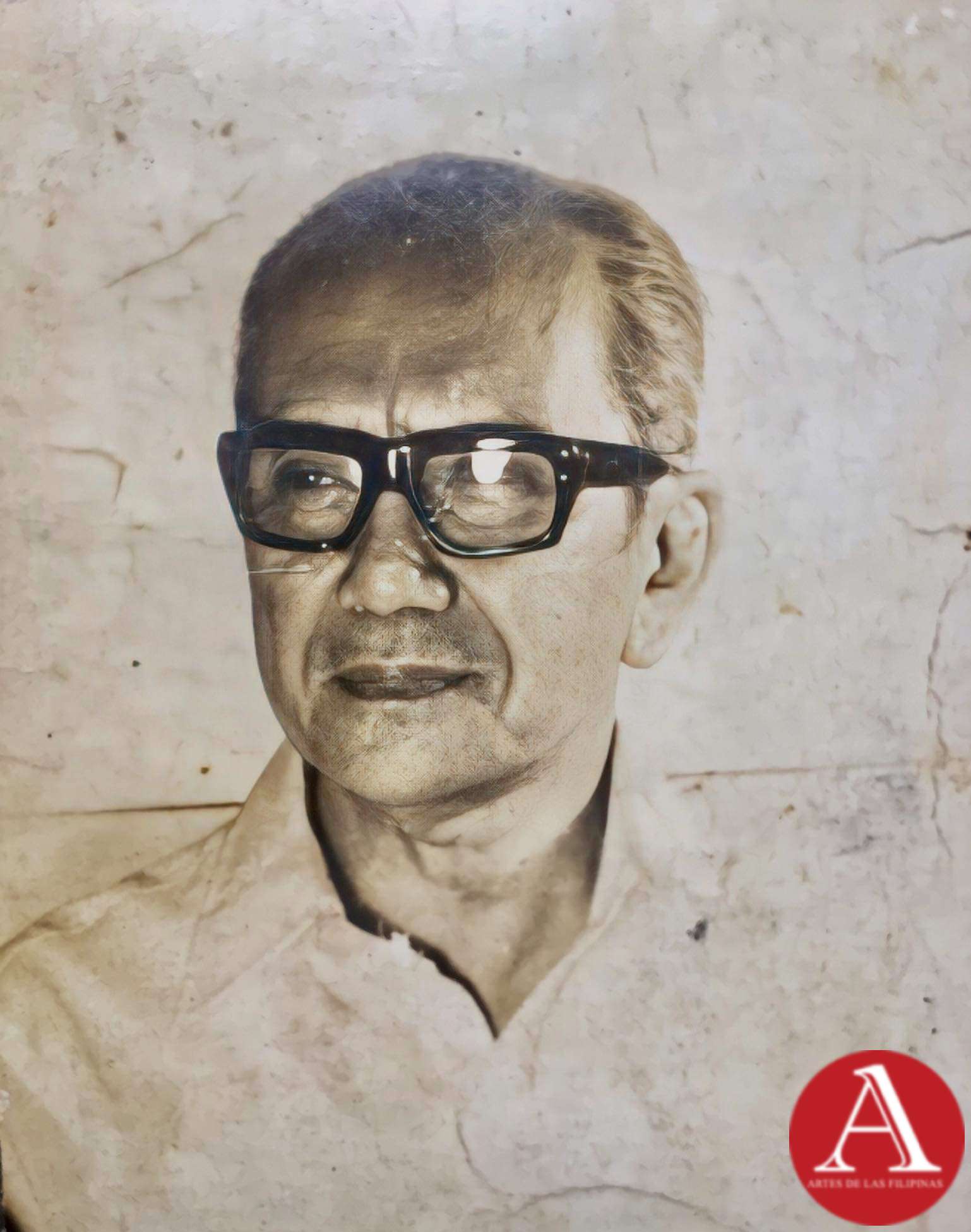

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISM

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISM.png) FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO

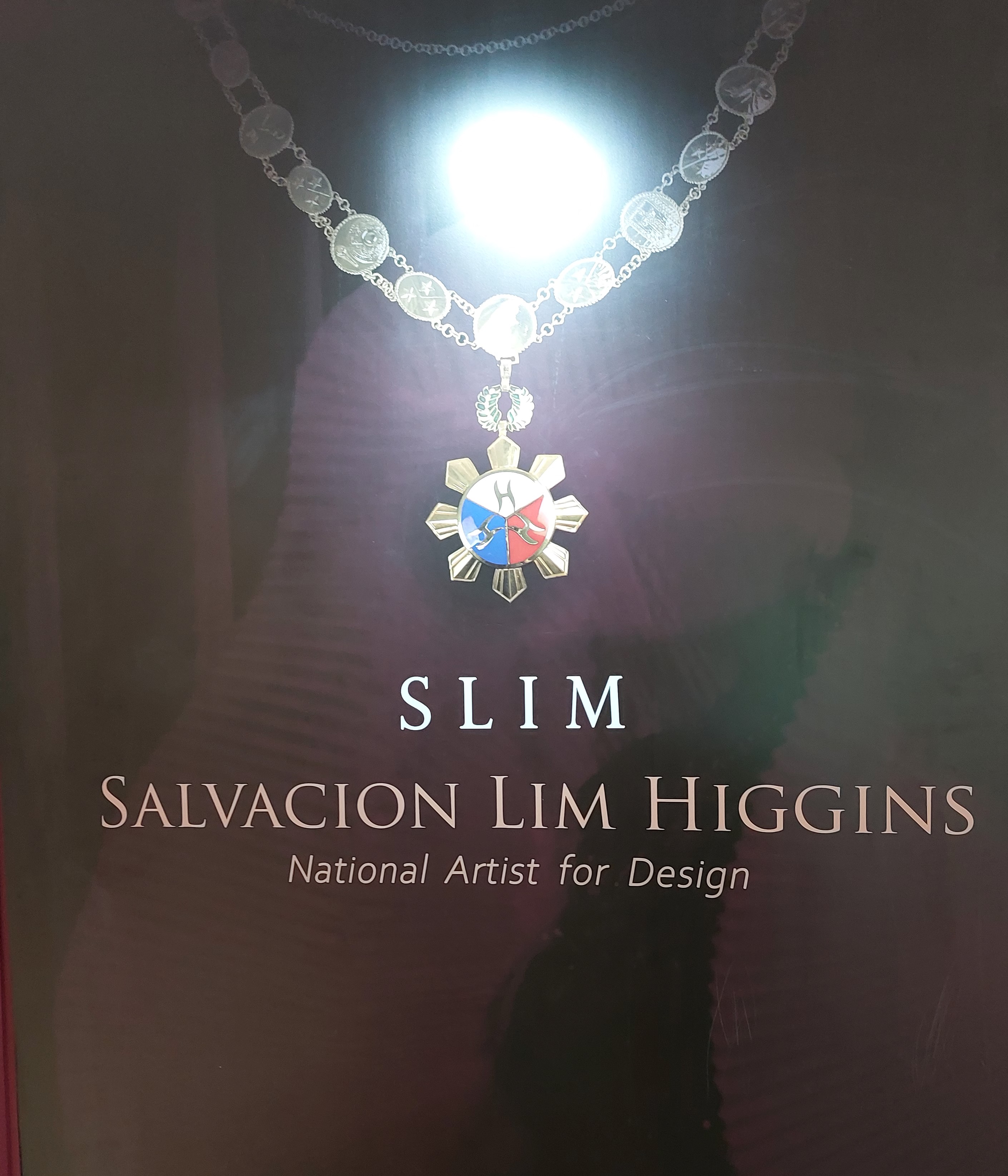

FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

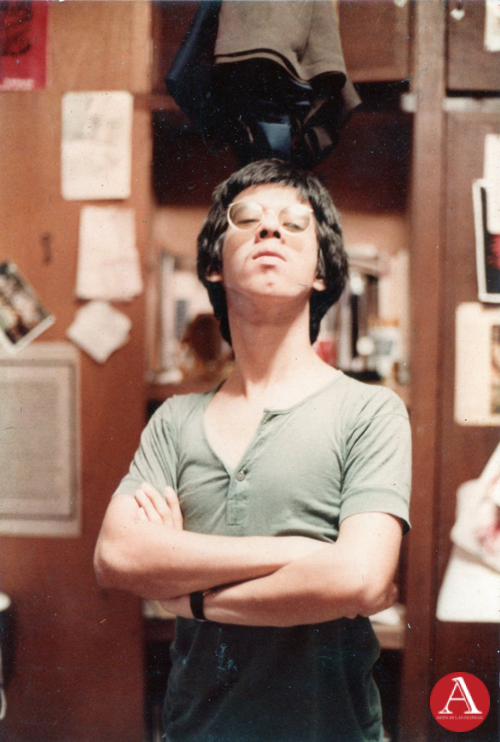

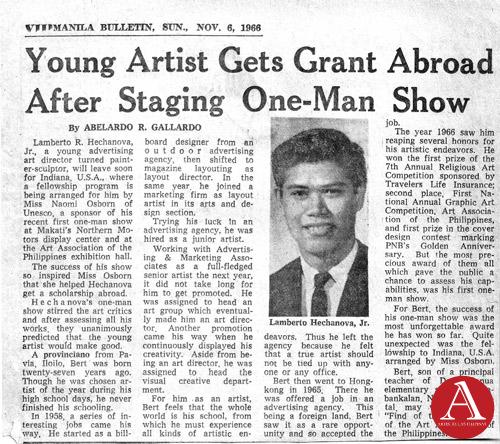

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery

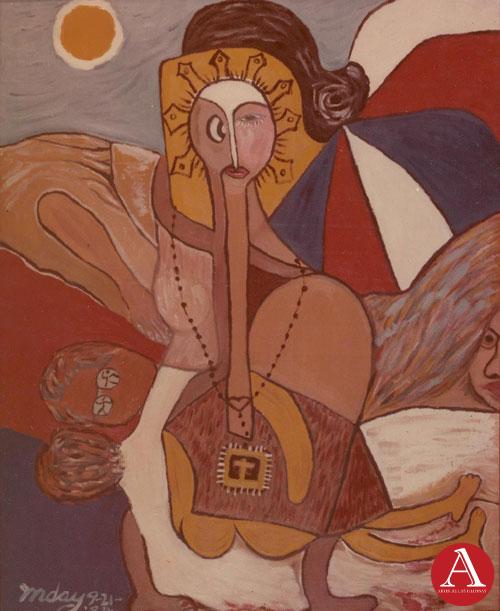

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday

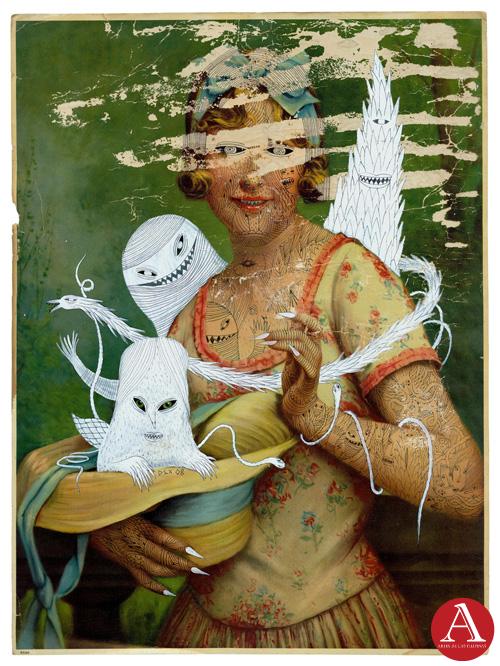

Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday Dex Fernandez As He Likes It

Dex Fernandez As He Likes It