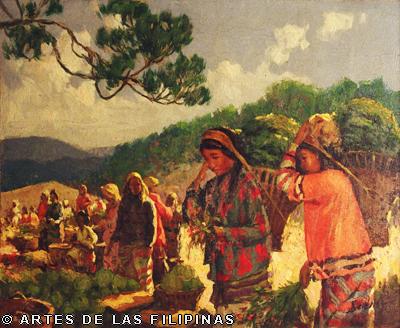

Silence of Centuries

MARIO DE RIVERA: Shape and Color of Memory

by: Joel Vega

August 2013–LIBERTAD in Mandaluyong City could be a typical street in busy Metro Manila with its row of apartments and the bustle of passing motorists. On number 26, a mix of potted plants flanked the door to the home of Mario de Rivera, one of the Philippines’ most prolific painters. There is stillness at De Rivera’s home as if the house has deliberately pushed away the ambient street noise to reflect a singular trait of its owner.

Described by the art critic Alice Guillermo as the creator of paintings with “sumptuous imagery…showing the rich confluence of cultures,” De Rivera has maintained a low but distinctive profile in the country’s art scene. The artist as a self-indulgent, garrulous creature would be a tag difficult to pin to De Rivera who often carefully picks his words.

Jardin Botanico

“Painting is the only way I can be totally myself,” says De Rivera when queried what prompted him, after several years of working overseas, to return some forty years ago to full-time painting. And, indeed, a passionate artistic engagement is often evident in the works of De Rivera where the viewer is entranced not only with imagery, colors and textures, but an amalgam that provides a hint to the Filipino psyche.

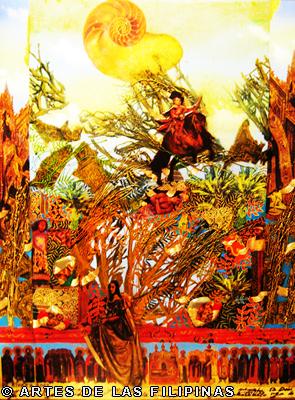

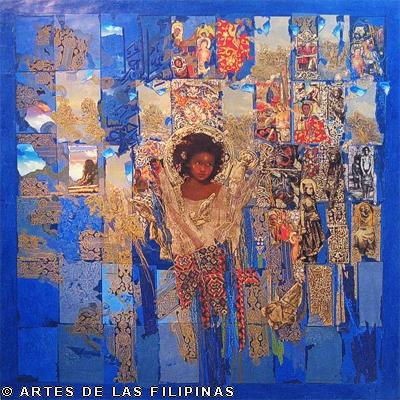

In a span of nearly four decades since his 1974 first solo exhibit in Manila, De Rivera has mined a rich visual imagery where Philippine Madonna’s are juxtaposed with Byzantine saints, rich earth colours are set-off by lace-like fragments and the pictorial space is filled with arabesques, cathedral spires, archetypal figures from Philippine ethnic tribes to direct citations of iconic Renaissance images such as Botticelli’s Venus, a Velasquez horse-riding prince and Russian icons.

In The Land of Saints and Horses

To again quote Guillermo, in De Rivera’s work “traditions co-mingle…conveying the artist’s faith in the essential unity of humankind—that cultures from all parts of the globe participate in a universal discourse and contribute to commonly shared meanings.”

Open histories and narratives are, thus, the main touchstones in De Rivera’s work and the artist himself provides confirmation. “We Filipinos in general are more outward-looking than our other Asian neighbors. It is both good and bad since there are always two ways of looking at things. But when cultures cross boundaries there’s always a good chance great things are born,” says De Rivera.

Conquistador 3

De Rivera reflects on the diasporic path pursued by many Filipinos in recent years: “Migration can result in values and ideas coming into conflict. And new ideas come into being. But more than that, it is finding how much we have in common with the rest of the world that propels my art,” he adds.

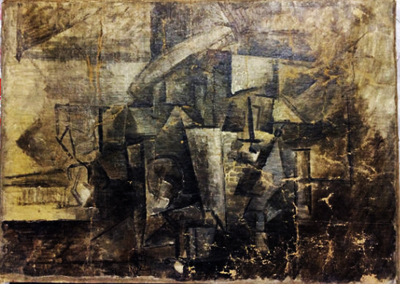

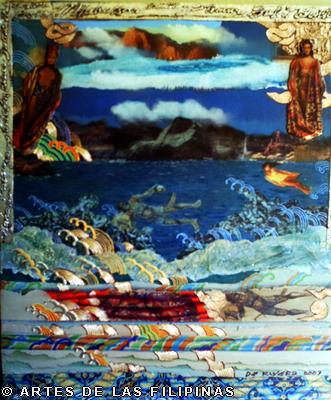

If the artist’s acknowledgement of cultural diversity leaves an indelible mark on his work, it is memory that often underpins De Rivera’s creative approach. He employs techniques in photo transfers, modeling paste and gold-leaf to create complex floral patterns and fibre-like layers, a visual language that often returns to or surfaces in fragments, echoing the slippery nature of memory.

Between Kisar and Makassar

“Memory is central in my art making. Not in a conscious way, but everything just floats in random fashion when I’m in front of my canvas,” De Rivera says. Thus, sepia photos and figures are half-buried in encrustations and relief surfaces as in the series People of Heaven (1-3) or are torn at the corners or framed. Embossed leaves and stones flit or float on the pictorial space (Piedras Sagradas series) and pina or jusi-like layers are built with serrated edges. De Rivera has perfected the latter technique of simulating pina or tinalak fibres, and his propensity for fibre motifs that recur in most of his works somehow pays a tribute to his mother who is accomplished in dressmaking.

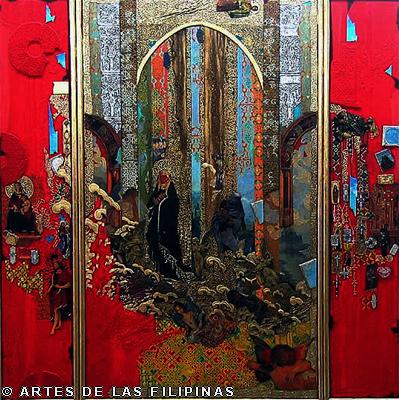

Cordon de la Eternidad

Color is also masterly orchestrated in a De Rivera piece, playing a lyrical note or setting off associations. In the 2003 piece Cordon de la Eternidad the rich reds and gold’s do not overwhelm but served to unify and present the various facets of the feminine through the centuries. Gold has always been associated with the sacred and De Rivera’s handling of gold in his work is almost akin to a spiritual homage or invocation of the eternal (and spiritual).

In Lokum Beyoglu 1 (2008), the triptych showcases De Rivera’s mastery in the handling of color where his signature modelling paste technique provides accent in the form of randomly scattered ‘stones’ that form or act as a ‘bridge’ across the three panels. The pictorial ground, studded with detail and flitting images of insects and clouds, has a kaleidoscopic effect, at once fragmentary and lyrical.

In De Rivera’s oeuvre color and memory are often closely entwined to trigger associations and this is reflected in the 2003 work Paradise of Ashes with its palette of dusty grey monotones that also denote spatial movements on a fragmented landscape. Paradise of Ashes, interestingly, deviates from the usually sumptuous De Rivera palette and rightly so since the piece can be described as a meditation on the devastation in Northern Philippines following the 1991 Pinatubo volcanic eruption.

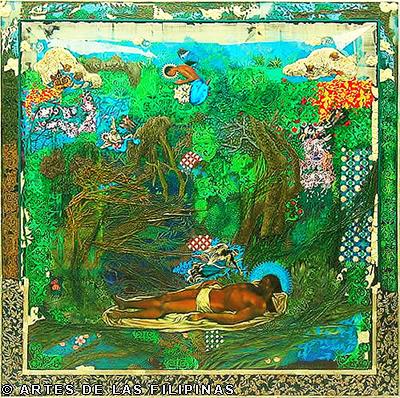

Nuestra Eden Perdido

But it was the earlier 2001 work “Nuestra Eden Perdido” (Our Endangered Eden) which pushed De Rivera to the international art scene when he won the Excellence Award in March 2003 from the Beppu Contemporary Art Exhibits in Japan, besting a thousand entries from across the world. A triptych, the work is a superb symphony of colours, fragments and textures, contemplating on the slow demise of the natural world and the innocent. As described by critics the piece shows “… mutated flowers meeting spaceships and modern icons like rum bottle labels, fabric swatches and postage stamps, flanked by a Madonna and child and a bahag-clad (loin cloth) denizen of simpler times and places.”

People of Heaven

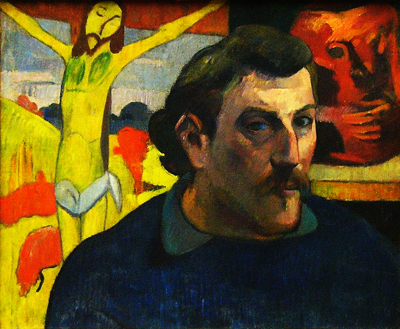

Nowadays when the newest art works are increasingly occupying the conceptual terrain and when the aesthetic experience and approach are often pushed to the background under heavy bombardment from ‘shock art’ and their variants, Filipino artists are confronted with the infinite chasms and splits that plague the art world.

Faced with this question, De Rivera responds in an unperturbed, characteristic manner:

“I grew up in a gentler, kinder world that saw things in a different perspective. Aesthetics, as I know it, is a world away from what seems to be or what passes as such these days. It takes a totally different mindset to appreciate conceptual art,” says De Rivera as he pauses and carefully adds: “It (appreciation of conceptual art) doesn’t come easy but having come face to face with great modern art such as Yayoi Kusama’s has totally taken me.”

One can only nod in agreement in the same way that one opens up to the exalting colors, textures and landscapes that are uniquely De Rivera’s.

Minglanilla 1

Manila-born Joel Vega works as a medical journalist and publications editor in the Netherlands. He has won the 2010 Carlos Palanca Literary Award for Poetry in English. His poems were published in Versal (Amsterdam), Runes, Sand (Berlin), Poetry Salzburg Review, Vespertine Press (San Francisco), Tale of Three Cities (London) and other US and European literary journals. Joel graduated with an AB Mass Communication degree from the University of the Philippines Los Baños.