Brief Sketch of the History of Plastic-Graphic Arts in the Philippines

(First of Two Parts)

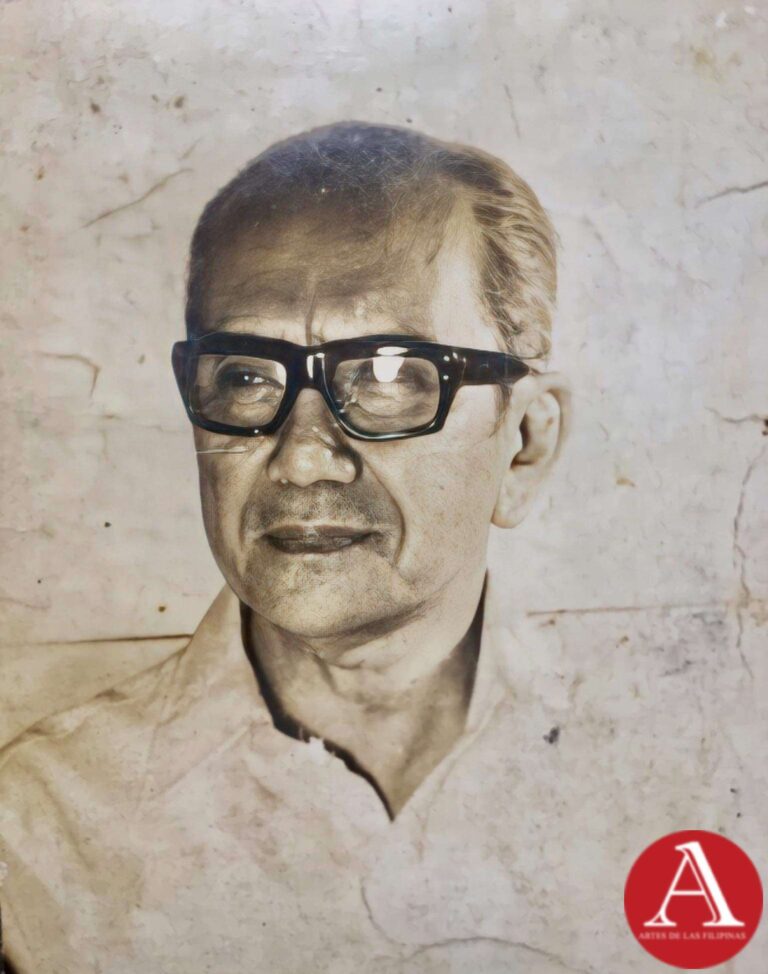

by: Fabian de la Rosa

Director, School of Fine Arts, University of the Philippines

September 2013--The best starting point in the history of Philippine art is probably the sixteenth century, with the implantation of Spanish sovereignty over the islands.

During the pre-Spanish period, the Philippines already enjoyed a certain degree of civilization. The unit of social and political organization varied in size from 5 to 7,000 inhabitants, and was known as “barangay”. The people fabricated different kinds of boats, fishing apparatus, and finished arts; they wove textiles from abaca, pineapple, cotton, and silk which came from China; they embroidered and carved sculptures symbolic of their ancestors whom they called “anitos”. According to [Trinidad H.] Pardo de Tavera, they were expert silver, gold and coppersmiths, working on these minerals for artistic jewels and for bedecking their weapons and arms. The late distinguished artist and sculptor, Jose Ma. Asuncion, says in this connection: “During the first period (pre-Spanish) Filipino art was but the shadow of that existing in the Asiatic continent, eminently oriental, with some local characteristic which were developed in manner parallel to the different foci of Oriental civilization with which we were in close contact, such as India, China, Indo-China, Japan, Borneo, Sumatra, Java and the Moluccas… Upon the implantation of Spanish sovereignty over these Islands, every vestige of this Oriental art was swept away in the center of the Philippines Archipelago.” Further he says, “ architecture, sculpture and painting, if at all they existed by reason of the necessities and beliefs then obtaining, left no archeological traces in forgotten corners of the Philippines.”

Until now, these are the only available data on Filipino art during the pre-Spanish period. As can easily be seen, these observations are based on deductions which may be considered reasonable, but for the purpose of the present treatment, it would seem desirable to look for more authoritative sources. On the other hand, the bows and arrows, spears, blades, poniards, coselettes, and helmets of wood or copper, etc., as the collars, bracelets and other objects of more or less artistic value that can still be seen in our days, cannot be considered as basis elements for our starting point in the treatment of Filipino art.

Having thus considered briefly the character of Filipino art during the pre-Spanish period, we now come to the period of the Spanish conquest in order to understand the trend of the development of our plastic-graphic arts.

Architecture

When the Spaniards landed in the Philippines they found no other kind of buildings than houses or huts made of wood, bamboo and nipa. These were constructed over high wooden posts, in order to afford enough room for the servants. Very frequently towns were found raised on water, at the mouth of rivers, lake or on the seashores.

The architecture of purely Malayan taste, made of available materials abundantly provided by the flora of the seventeenth century, during which the new San Augustine Church was erected, made entirely of brick and stone under the direction of Architect Juan Macias, who passed away shortly after the first foundations were laid down. The work was continued by Father Antonio Herrera, son of the nephew of the famous architect of the same name who built the El Escorial of Spain.

The Church of Saint Augustine is a mixture of Romanic and Renaissance style. A feature to be admired in the interior is the two elliptical arches supporting the choir as well as the dome. It does not seem to keep the right ceiling in proportion because of the height of the parabolas although such apparent disproportion obeys more to a deviation of the established principals of the architecture of the Renaissance to the desire of the builder to safeguard the structure from the frequent earthquakes and violent seismic disturbances of the country and to the prevalence then of the architectural school of Herrera, which centralized the beauty in the solidity and magnificence of the massive parts. The Monastery of Saint Dominic followed this church of Saint Augustine in point of antiquity of construction. It was built in 1587, having been designed by a member of the same order, but the church and monastery which now stand were created in 1870 by the noted Filipino architect Roxas. The style employed was the Gothic.

Regarding this architect, Miss N. Norton, a noted American writer, who resided in the country for several years, says in one of her books: “Manila has many notable monuments in domestic architecture. If the blending of a romantic and renaissance styles and its native adaptation did not always become a success, the city can at least be proud of having had an architect which left an impress in the temples and private buildings of which he has constructed many a number – the stamp of his genius.”

Mr. Roxas stayed for three years in Calcutta, way back in 1840, and from thence he left for England where he resided for fourteen years and two in France and Spain. His long residence in Great Britain is responsible for his preference, upon his return to the Islands, of Roman and Greek features. According to critics in architecture, Mr. Roxas had the rare privilege, seldom given to the artists, of stamping his creation with dignity and circumspection, aside from the feeling of agreeable pleasantness which they produce in the soul of visitors and observers as a result of harmony of the whole. He left notable works, among which those that deserve special mention are: the Church of Saint Dominic, that of Bacoor in Cavite and those in other places of the Philippines. He also collaborated in the designing of the temple of the Jesuits and in order not to unduly prolong the enumeration, among those private residences constructed by him, the peer of them all is the residence of Sra. Carmen Roxas, on Calle Solano, an edifice which is considered without equal in its class in point of its lines of elegant style and its perfect proportions enjoying the distinctions of presenting “no trace of asperity nor a suggestion of vulgarity in that conglomeration of molave”.

Since the first century of the Spanish rule, important buildings have been erected, among which are the Royal Palace, constructed in 1690; the Real Fuerza de Santiago by Legaspi reconstructed by Goiti and later fortified and then reconstructed as it is today by D. Diego Jordan, during the time of Governor Dasmariñas; the old Ayuntamiento, destroyed during the memorable earthquake of 1863 “more beautiful in its external aspect than the present edifice”; the church of the Franciscan Order; the Cathedral, of Byzantine style, was erected during the years 1878 – 79; the temple of San Sebastian, of Gothic architecture, of iron forged in Belgium, and finally some private residences situated in Intramuros in General Solano and San Sebastian Streets (now R. Hidalgo) and in the districts of Ermita and Malate. All these ancient and modern buildings, besides others which have been omitted in the interest of brevity, truly merit to be considered as monumental accomplishments not only because of their antiquity or their artistic merits but also because in some of them, those of a religious nature, the whole history of Christian civilization is impressed, in beautiful and indelible characters.

It could be noticed during the past regime that, notwithstanding the heterogeneity in the styles of architecture, the greater part of which were imported from Europe, there were certain local tendencies thriving in the architectural field which, if left to its onward march, would have in the long run climaxed into a combined Oriental-European architecture.

Manila had the rare fortune of having the services of another notable architect-builder in the person of a Spaniard, Senor Hervas, who occupied the position of municipal architect of the City of Manila during the years 1887 – 1893. He specially excelled in the construction of residences, not merely dwelling places, the most notable among which are the office of Rafel Perez, on Calle Anloague, the Inchausti brothers, the Central Station of the Manila-Dagupan Railroad in Manila, the Hospital of San Pablo, of Byzantine style; the convent of the Asuncion on Calle Herran, the “Estrella del Norte” on the Escolta; “El Oriente”, plaza de Binondo and last, the tobacco factory of “La Insular”. According to many, however, his masterpiece is the edifice now known as “Monte de Piedad” of Greek style, whose marble columns were imported from Italy.

Thus was the normal course of events relative to the progress in the arts in our country when, unexpectedly, the war between Spain and the United States of America broke out. Having displaced Spain, United States took the reins of power and established in this country a new system of education, implanted and imported new industries and with these opened up new sources of income for the government. The new government gave impetus to public works, and to other lines, and even in the realms of the spirit, considered as a sacred depository of great ideas and noble thoughts, and radical changes were brought by the new regime.

In the realm of art, however, it did not go to the sad extreme of destroying what had been created by artists of the preceding regime, similar to that which happened with the artistic works of Malayan Filipinos at the time when they were conquered by Spain during the Sixteenth century.

And now, one may ask: What is the actual status of Philippine architecture? Attention is invited to the following considerations:

As already alluded to above, during the past regime certain tendencies were observable looking toward the crystallization in the more or less immediate future, of a real national architecture. The child, as it were, had already gone through the period of adolescence, and was advancing to manhood, when unfortunately the war between Spain and the United States broke out, and impeded his growth. Since this historic event, the social stage has been transformed and consequently the work started under favorable auspices during the old regime had to suffer a setback. In its place, there is now beginning to assert itself a new mentality and with it is coming new orientation in the art of the constructor, although with still vague character. And this is undoubtedly the most crucial moment in the history of Philippine architecture, in which is required not only talent but also and perhaps in greater quantity prudence and a sense of proportion on the part of our architect and builders, as well as a sane and clear vision of the future. In line with this observation, it may be pertinent to note what Dr. T. Pardo de Tavera says: “The great defect consisted in the lack of a solid foundation of study, and therefore, the adaptation and introduction of different styles, without previous considerations of their suitability. The combination of forty individual musicians, each playing an entirely different tone does not constitute an orchestra. Therefore, many exotic importations joined together do not constitute an artistic harmonious whole. This same situation we find confirmed we find in some individual arts – in embroidery, for example, in which they have adopted European patterns without exhibiting any originality. With respect to form, there exist clear indications of native genius, but not in composition and style. Japan, on the other hand, has preserved its own school intact, almost free from foreign influences.”

Luckily not all is lost. The present generation counts on a good number of young architects who already constitute more of a reality than a promise. The country expects much of them in the development of their art, in the conservation of the spirit of the race, not in archaic efforts indicative of an atavistic but in actual manifestations in which the dynamism of the inner national feeling go together with the inescapable principles of the universal art, to present a faithful mirror of human progress. From this union of two distinct elements so harmoniously blended by a well-balanced mind will surge what is called originality in art, in the highest sense of the term. The experience of the past and the present point to one incontrovertible conclusion; that the Filipino, like the European or the American, is capable of scaling the highest summit of art, so long as he is given opportunity, time and money.

As it is not my intention, in starting this work, to devote much attention to a summary of Philippine architecture from the incipiency of American occupation, I shall only limit to give a few of my present impressions on the matter.

There are already sufficient numbers of constructions, some reproducing wholly European creations and styles; others, with seeming pretentions at originality, paying more attention to superfluity rather than to necessity; this being a fundamental requirement of architecture. As a result of this mixture, there is commingling too heterogeneous for the formation of a harmonious and typical whole – such as that which exist in a family, for example, whose members, while different from one another in facial features, color, stature, and in other respects, still preserve the link of common semblance popularly known as the “family air.” By means of this they do not greatly differ among themselves, preserving in this wise their unity in spite of their variety, one of the eternal and immutable principles of universal harmony. Aside from these defects which are natural, in every formative period of arts en every country, if we are going to consider separately each work, we will find that some bring great credit to their authors, and they will win prize even if brought to other soils where a true and intense appreciation of the beauty of architecture prevails.

Probably the one who distinguished himself most in stimulating original designing in architecture was Arcadio Arellano, son of an old native architect. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he tried and succeeded to depart from European and American models and started to use native plants and objects as decorative motives of his designs. He erected many monumental buildings, like those of “El 82” in Binondo and “Hotel de Francia” in Plaza Santa Cruz in the down-town districts. He also designed many beautiful residences in the different sections of the City of Manila and in the provinces.

To the Insular government belongs in a great measure the credit of being an effective instrumentality in bringing about great stimulus and remarkable progress in architecture. As early as the American occupation, the position of Consulting Architect was created in the Bureau of Public Works for the planning and designing of all insular, provincial and municipal works throughout the Philippine Islands. Many public school buildings, markets, town-halls and provincial capitols in all parts of the Philippine Islands had been constructed under the direction of the Bureau of Public Works. The schools and markets are necessarily of uniform standards but a great number of provincial capitols stand as monumental structures whose grandeur and beauty are unsurpassed anywhere.

Mr. Burnham, the well-known American Architect on city planning, was brought over in 1909, and after making an exhaustive study of the available sites for government buildings and private zones, in Manila and in Baguio with special reference to future and progress, left a manuscript of his work in what is known as the “Burnham Plan,” which gave the Insular government a definite layout to follow in building constructions, especially those pertaining to the government.

Among the buildings of architectural significance and beauty worth mentioning erected by the Insular government in the city of Manila are the National Library (now called the Legislative building), the Post Office, the Normal Hall, the Philippine General Hospital and the Manila Hotel.

Following in the footsteps of the government, many private firms and business houses have endeavored to build splendid structures which constitute the pride and the beauty of the city. The Masonic Temple can be mentioned as the forerunner of the “sky-scraper” type. It is made of concrete and rises in seven stories, of beautiful and dignified treatment and designing it can stand comparison with the pretentious buildings constructed in later years. The Pacific Commercial Co. building, the Chartered Bank building, the Perez Samanillo building, the Heacock building, the Lyric House, and innumerable others in the down-town districts and in Dewey boulevard are changing the sky-line of Manila and transforming it into a dazzling site and beautiful to look at.

Among the most notable living Filipino architects who are contributing to the glorification of Manila are men of artistic taste and ability, such as Juan Arellano, Andres Luna de San Pedro, Tomas Mapua, Carlos A. Barreto, Fernando Ocampo, Juan Nakpil and Antonio Toledo.

Before closing this part dealing on architecture, I wish to call attention to the fact that it has been my intention to enumerate in this pamphlet only a few to the best architects who save have already passed away, with examples of their masterpieces.

To be continued…

NOTE: The article, Brief History of Plastic-Graphic Arts in the Philippines written by Fabian de la Rosa that appeared as a chapter in the book, Encyclopedia of the Philippines The Literary of Philippine Literature Art and Science Volume Four published by P. Vera & Sons Company in 1935. To the best of the knowledge of Artes de las Filipinas, this article is no longer protected by copyright. This work is made available on this site for the sole purpose of information and is not made available for commercial purposes.