Brief Sketch of the History of Plastic-Graphic Arts in the Philippines

(Second of Two Parts)

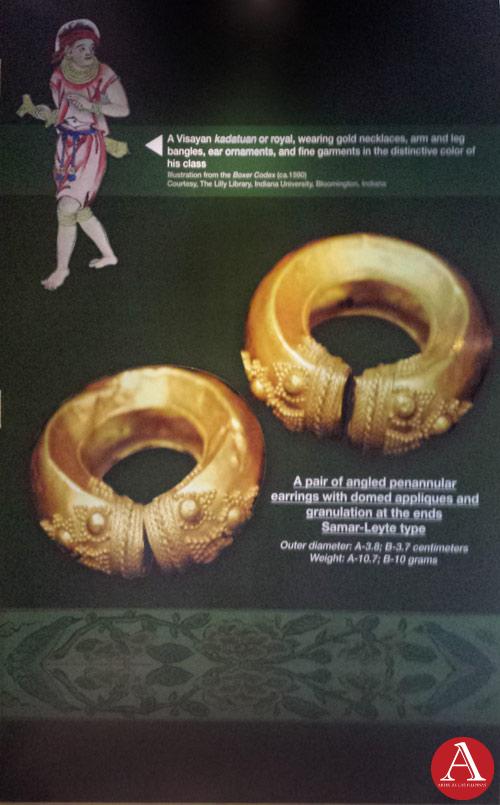

September 2013–In sculpture, we are face to face with a problem more difficult perhaps than that which we have encountered in the consideration of Philippines architecture, considering the fact that there is scarcity of authoritative data and proofs of the existence of an autochthonous art in sculpture. Not even the later epochs of pre-historic times, such as for example, that when for the first time Spain set her foot on this soil and found a civilization far advanced than that which she did imagine to exist among the Malayan Filipinos of those times, judging not according to western standards but merely reflecting the civilization of India, China, Arabia and Japan, were they able to leave a legacy to Spanish-Filipino generation something conclusive in matters of sculpture sufficient to enable that generation to determine the peculiarities of style even sculpture psychology, with which the artist, archeologist or the historian of art could solve more or less the problem touching the relation that could have existed between the pre-Spanish and the Hispano-Filipino styles.

Before the end of the Sixteenth century, the Augustinian fathers had established in their own convent an elementary school for the natives,which later on wasconverted into an Academy of Arts and Sciences, until the arrival of the Jesuits who took charge of the same. The artistic instruction gave good results; there sprung up a group of good artisans and artists of more than ordinary skill, who found continuous employment in works of ornamentation, especially in wood carving and in the making of religious figures of saint of which the churches and convent were in constant need during the first years of the conquest. Sculpture of this kind had to exhibit a severe hieratism, almost archaic and Byzantine taste, in their gestures and attitudes, in conformity with the Christian imposed on the religious art. The artist on his part, in the order to insure his job in conventual works which formed the only source of income for the sculptors and painters of those days, had to show religiosity and devotion and there were not a few who went to confession and communion before starting their day’s work. To all this may be added s detail which is not altogether destitute of interest, and which is this the calling of the painter and the sculptor in the colonies of Spain was made difficult because of the interference of a class of individuals well-known for their systematic bigotry in opposition to the independence of arts.

Fortunately, however, for all particularly for art, on the first of May, 1785 during the reign of Charles III, a royal decree was promulgated authorizing the free exercise of the art profession by nationals as well as by foreigners, without restriction or payment of fees. This happy event should have caused great satisfaction among artists because of the undeniable benefit that said decree meant from a material and spiritual standpoint, but they did not seem to understand it that way or were not made acquainted with the real meaning of the royal document, they barely profited form that generous concession.

However, the reason of the apparent indifference shown by the artist is in that case should not be attributed exclusively to said circumstances. In those times the country did not have true educators and good modelswho could duly help them in the difficult training of arts. They have acquired their meager technical and artistic knowledge only from amateur instructors with poor qualifications for the teaching of art.

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, art gradually developed, impelled by the irresistible force of the universal progress, and the influence of Spanish arts became more and more noticeable; sculpture in its progressive evolution evinced in an indubitable manners the influence of the school of Martinez Montanez y Arcillo, illustrious Spanish sculpture of the Seventeenth century who was a specialist in wooden religious sculpture. From time to time there came from far Mexico works of art which, with those coming from Spain, increased the number of models of which our artist were in great need, but it is to be wondered that notwithstanding these foreign influences, which left their impress on the production of the Philippine sculptures, nevertheless it could be seen in them unmistakable tarces of original aesthetic feelings deeply rooted in the Malayan Oriental soul.

In the first half of the Nineteenth century, sculpture like its kindred arts Architecture and Painting acquired a notable development, with a predominance of works of a religious and mystical nature both in number and in quality which sculpture form life and monumental sculpture were almost unknown.

We do not have the means of those sculptors who lived before Nineteenth Century but we can mention the names of some of those who become prominent in the last third of the same century until the beginnings of the present century, all of them now dead; Manuel Asuncion, Leoncio Asuncion, Jose Arevalo, Romualdo de Jesus, Domingo Teotico, Sotero Garcia, Manuel Flores,CrispuloJocson, Hipolito Salas. I see no reason why I should not add to this distinguished list the glorious name of Rizal, who we are proud to designate as our greatest patriot. He was not a professional sculptor in the ordinary sense of this word. His desire, in learning sculpture, was no other, judging from what can be inferred from his plastic creations, than to be able to make use of such artistic means, the most emphatical of all, for the external expression of his feelings and ideas in precise, sensible and eloquent manner, conditions which only can be found in the highest degree in sculpture. Rizal, as a physician, was fully conversant with the human anatomy, a knowledge of which enabled Michael Angelo and August Rodinto produce their marvellous and unsurpassed paintings, overflowing with life and evocative of eternity. Such knowledge enabled our illustrious countryman to finish his most perfect work in modeling, the beautiful bust of the Jesuit, P. Guerrico, who was his professor at the Ateneo de Manila. This is a work which I may dare classify among the best sculptural portraits ever produced in the Philippines by native artists because of the harmonious blending of the physical likeness of the person and the faithful interpretation of his moral character. With a little variance in wording, the following sentences of a famous Spanish lecturer can be aptly applied to him. “He had the complete mastery of the ways and means of the special technique of his art, at the same time he possessed a thorough and exact knowledge of man, which can only be attained through a philosophical study of the human being as well as of the constitution and the different parts of the human body, specially the face with its numberless variations, some of which of such subtlety and delicacy, that required for its discovery a sort of intellectual microscope,”

Although the art of painting is quite developed nowadays in this country we do not unfortunately have any positive evidence of its existence before the coming of the Spaniards. We should not be regretting this unfortunate condition had the Filipinos, during the pre-Spanish times, counted with buildings made of stone or other materials of greater resistance and durability than wood, bamboo and nipa. Because in such case, even assuming that earthquakes and typhoons could have totally or partially destroyed said constructions, we can safely say that the drawings, paintings and bass reliefs contained therein would not have completely disappeared, as it happened in other countries very much older than ours wherein archeology has discovered and is still discovering fragments of artistic objects, some of them in good condition in the midst of the ruins and rubbish of buildings already demolished centuries ago either by a catastrophe of geological or atmospherical origin or by men themselves.

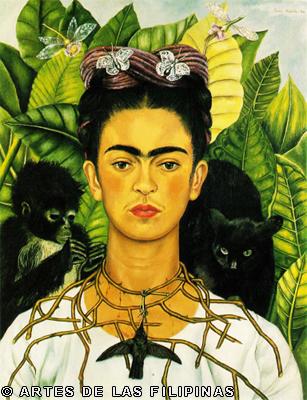

Like Sculpture, pictorial arts in the Philippines began with the settlement of the Spaniards in the country. As in the case of architecture and sculpture, it was the priests who first made use of painting fill certain conditions in religious cult. They kept painters busy, some in the reproduction in oil of images of the Virgin and other saints, other in copying from engravings brought from the Mother country certain miraculous facts, religious events and other kindred subjects. And the artist, with little knowledge of painting, perspective and color and completely ignorant of the human anatomy, engaged themselves enthusiastically in their tasks, with solemn pride that their works were destined to find places in the altars or hung on the walls of the church and to be regarded therefore, as sacred objects, respected and honored by the big crowd which usually went to the church to discharge their duties as Christias.

In the meantime, the influence of the Spanish school became more noticeable from day to day, especially that of Seville, at the head of which are such luminaries of the pictorials arts as Murrilo, Alonzo Cano and Pedro de Moya to which school, it was said, they gave to the Catholic religion all the sincerity and ingenuity that could entice the human soul and ingrained therein all Christian beliefs.

At last came the 19th century. Between the years 1815-1820, the school of fine arts was founded in the Philippines, and located at its capital, through the private initiative of a Filipino painter, Damian Domingo, a native of Tondo. This school achieved an enviable record a few years after its foundation. The “Real SociedadEconomica” of these Islands, seeing the increasing number of students enrolled in the school, decided on June 13, 1829, to take over the management of the school, retaining at its head, its founder Damian Domingo, with a monthly compensation of twenty-five pesos.

I believe it is not out of place here to mention that before the opening of this school, or to be exact, since the last years of the 18th century, the Filipino painters were not confined anymore to religious painting; also they were making life portraits. Their technique consisted in polishing a cloth to the extreme and softly extending over it the color in order that the slight brush traces may not appear. They took great care even of the slightest details, from the beginning to the end, and took pride in showing one by one the hair and eyebrows. They lacked the real technique, and did not understand that besides the likeness of the portraits, it was necessary, through the attitude and expression, to represent that whatis called character. It can be said that they had a uniform standard in pictures.

In the meantime, Damian Domingo was gaining renown as an artist, to such an that even Governors General themselves called him to paint their pictures, some of which still can be seen in trhe gallery of the Malacaňang Palace. He died at the age of 34.

Upon the death of Damian Domingo, teaching in said school was temporarily suspended. The Spanish government out of interest felt towards the Filipino youth who had shown aptitude in the cultivation of plastic arts, hastened to establish an official Academy of Fine Arts to succeed that of Damian Domongo. In order to give encouragement and increase the efficiency of artistic education through up-to -date methods, similar to those given in Spain, the government brought some experienced professors like Cortina, Nieto and another who remained in the Islands until 1860, having as their assistants Filipino painters. They were succeeded by a distinguished Spanish painter, Agustin Saez, well-known for his eminent qualifications as Sr. Lorenzo Guerrero and Sr. Lorenzo Rocha, both Filipinos, to assist him. In 1891, sickly and enfeebled, he had to resign his position from the Academy. He was succeeded by Mr. Lorenzo Rocha, under whose time the reorganization of the technique and introducing more theoretical and practical subjects, and changing the name of the Academy into that of “Escuela Superior de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado de Manila.”

Other painters who came after Damian Domingo achieved success in their profession, among whom were Antonio Malantic, author of numerous pictures of outstanding merits as far as likeness was concerned; Isidro Arceo, Jose Asuncion, Hilarion Asuncion, D. Gomez who not only devoted themselves to the making of religious painting but also to portraits. Later on came other groups of painters who showed higher culture, better technique, greater knowledge and more proper application of certain science allied to painting. I remember the following: Felipe Roxas, a landscape painter and the most learned copyist among the Filipinos that I remember; Lorenzo Guerrero, the most learned Filipinos painter who cultivative poetry and literature at the same time and was not indifferent to music. This artist possessed, in the highest degree never yet attained by any one, the art of artistic instruction. His great success in the profession lasted as long as he lived, and we can say that the best artists produced by the country since then acquired more or less their training form his teaching and seasoned counsels. Miguel Zaragosa is another painter who, in addition to his polished technique and his deep understanding of the different schools and styles of Europe, was also a writer, newspaperman, short-story writer, and an art critic; ToribioAntillon was the most popular among the few Filipinos who took up scenographic painting. He learned his art from the Italian masters, Alberoni and Dibella, authors of the decorative painting in the church of Saint Augutine; Eusebio Santos, Manuel and Anselmo Espiritu brothers, took up historical painting; Simeon Flores y de la Rosa, life painter of strong artistic personality, who painted also religious pictures, some of which have been awarded prizes in national and foreign exposition; Felix Martinez, land scape painter, author of land sketches and religious painting; Jose M. Asuncion, who especialized in the branch of painting known as “still life” and at the same time devoted himself with notable ability, to the studies of art, archeology, and journalism; Rafeal Enriquez, who spent the greater part of his life in Europe and whose best works remained there. He was an enthusiastic admirer of Goya and Velasquez, the author of “La Rendicion de Breda” and “lasHilanderas,” which exerted a very strong influence on his works. We cannot conclude this narration without mentioning the two indisputable sovereigns of Philippine painting, Juan Luna and Felix R. Hidalgo.

After his preliminary study of art under the authorship of Agustin Saez, Luna continued practisingpainting, but this time under the guidance of the illustrious Lorenzo Guerrero, mentioned above who, in fact, paved for him the way to glory and immortality, urging him to go to Europe, where shortly afterwards he won artistic triumphs which found echo in all the parts of the civilized world, raising him to the rank of world celebrity when he had scarcely reached 27 years. Notwithstanding his great admiration for Velasquez, he was rather influenced in some of his works, though slightly by the admirable technique of the great Rosales; on the other hand in his other productions, there are traces of Velasquez’ art, as can be detected in some of his pictures, as for example, “La Muerto de Cleopatra,” “El Pacto de Sangre,” “Ecce Homo.”And others. Having moved to Paris, where he lived for many years, we need not say that, the modern French school accorded a good deal of influence upon him, as can be noticed from his most disputed picture “Pueblo y Reyes” in regards to color and atmosphere. But what was admirable in Luna is that in spite of these influences, he preserves intact and strong his artistic individuality, a quality inherent in genius.

Like Luna, Resurreccion Hidalgo was a pupil of Saez, while he was studying in Manila. Later on he left for Europe for the purpose of furthering his the School of Fine Arts in Madrid, moving after to Rome, and lastly to the capital of art and culture, Paris where he lived for more than twenty years. There he produced his best pictures, among which the following deserve special mention: “Las VirgenesCristianas,” “Edipo y Antigona” “El Aqueronte,” etc. he distinguished himself to the highest degree by his knowledge of drawing, modelling and working on darkness and light. He had a complete mastery of composition. He was very fond of music, his favorite instrument being violin which he played with perfection. His pictures are acattered in Europe in the Philippines and in America. He was an artist of vast culture, a fact which made him highly appreciated by the intellectuals of the capital of France.

Luna and Hidalgo in raising the name of the Philippines to great heights, showed to the world that our country, with due training, can reach the level reached by other more advances nations and can reach the level reached by other more advanced nations and can cooperate with them in the grand undertaking of human progress, not only in material things, but also in those and selected of the spirit, in destructible and imperishable.

“La Escuela Superior de Pintura, Escultura y Grabadode Manila” closed its doors at the end of the Spanish sovereignty. In mentioning this school, it is not possible to forget the illustrious name of Melecio Figueroa, professor of engraving in the same, who was awarded various prizes and diplomas in Europe and America, the immortal authors of our national currency, the Conant. He is the only Filipino engraver who had developed said art from its purely artistic aspect with unsurpassed efficiency and enviable success. It is indeed a matter of regret that this art, of delicate and gracious beauty, could not count on more devotees in the country. In Europe, America and Japan there are many who devote their time to this art as can be seen form the national and international expositions held in said countries.

In 1909, a new School of Fine Arts was Established through the initiatives of local artist supported by other persons interested in art. It was made a branch of the State University, its first director being the painter Rafael Enriquez, and its first secretary, Jose M. Asuncion, Metioned above.

From the above account we can draw clearly one inference, and that the history of Philippine art is very brief, especially if it is taken as a whole and compared with those of the great nations, not only in Europe but also in Asia and America; for strange as it may seem, in such a long span of time, almost four centuries, the Philippines did not produced but four or five artists of international renown, when other nations produced hundreds of them in the same space of time. I think we can attribute this scarcity of artists to various causes. First, that we lived almost isolated from the advanced western nations, the cradle of our present culture and civilization, and then the means of transportation between Europe and the Philippines at the time were very inadequate as a consequence of which the Filipino artist could not establish direct contact with that environment of incessant artistic activity and to have an interchange of impression and ideas with the most accomplished, in art, of that powerful society; because it is a matter of common knowledge that art, in order to thrive and develop in a certain country, needs inspiration from what is produced beyond the national frontiers. A prolonged isolation will give place to declineand deterioration as can be learned from history; but above all, it is absolutely indispensable, necessary for the art, to breathe the air of freedom, for a subject country can hardly give artists in the strict meaning of the word. In the second place, and here we shall quote a paragraph from a lecture of an eminent Filipino statesman, who died a few years ago, touching upon a plan (or a dream, according to him) of a tendencious, conservative and exclusivistic education. |”It is not surprising to find such desideratum in a people who were up to this time educated under a Catholic monarchy, whose teaching have always been dogmatic and fenced within conservative ground. In politics the principle of divine rights of king was taught, to which principle was, of course, subordinated the blind obedience to the authority, the nation of the governing classes, who derive its power from royal authority and of the subject classes who are formed by the people born to serve the king and had to mould their desires, aspirations and actions of the sovereign or his representatives. In religion, beliefs are not deduced by the individual from his own observations or individuals judgments but he learns them in the form of dogmas and principles which under faith he had to accept from others as good, truthful, indisputable and absolute.”

I will conclude with the following phrases of a great Spanish art critic: “Art, because of its abstract character, its spiritual nature, is always at the head of all psychic energies, looking in the infinite the supreme human ideal. For this reason, art cannot be subject to anything nor to anybody; for this reason art needs complete freedom where it can move, develop and expand, and for this reason it sides always with the political and religious schools which offer broader horizons to man.” NOTE: The article, Brief History of Plastic-Graphic Arts in the Philippines written by Fabian de la Rosa that appeared as a chapter in the book, Encyclopedia of the Philippines The Literary of Philippine Literature Art and Science Volume Four published by P. Vera & Sons Company in 1935. To the best of the knowledge of Artes de las Filipinas, this article is no longer protected by copyright. This work is made available on this site for the sole purpose of information and is not made available for commercial purposes.