How Van Gogh’s Sunflowers came into bloom

by: Frances Spalding

January 2014—Van Gogh’s Sunflowers are among the most famous paintings in the world. As two of the originals are shown in the National Gallery, Frances Spalding looks back at the uproar and anguish they provoked

At first nobody wanted them. Van Gogh painted four images of sunflowers in a pot, and then three copies that depart in many details from the originals. Together, they amount to an iconic body of work, representative of his creative powers at their height. Yet the first time one was exhibited in his lifetime it caused uproar.

Having been invited to show work alongside Les Vingt, an avant-garde group of 20 artists in Brussels, in January 1890, Van Gogh consulted his brother Theo as to what he should send. Theo recommended the sunflowers and explained why. “I’ve put one of the sunflowers on the mantelpiece in our dining room. It has the effect of a piece of fabric embroidered with satin and gold, it’s magnificent.” But such richness and beauty, achieved by means of Van Gogh’s stark simplicity and strong colour, was not apparent to others. The artist Henry de Groux threatened to remove his own work from the 1890 exhibition if he found it in the same room as “the laughable pot of sunflowers by Mr Vincent”. As Van Gogh’s artist friendsToulouse-Lautrec and Paul Signac were present when this was said, the evening ended in chaos, and a fight was only narrowly avoided. The next morning, De Groux resigned. To the critic of Le Journal de Charleroi, it was understandable: this artist had been “very justly exasperated” by Van Gogh’s sunflowers.

Today, four of these seven sunflower paintings are in public collections. Two of the four originals can be seen in London from 25 January, when the one belonging to Munich’s Neue Pinakothek joins the one in theNational Gallery. Anyone who tried to buy Christmas cards last year at the National will have been forewarned. Almost half the Christmas merchandise, or so it seemed to this disgruntled visitor, was covered with sunflowers – fridge magnets, drying-up cloths, mugs, table mats, coasters, diaries, address books, even spectacle cloths and cases. When Martin Bailey, the Van Gogh expert and journalist, estimates that about 5 million people see Van Gogh’s sunflowers every year, he is talking about the oil paintings, not the ubiquitous reproductions they have spawned. These may indeed have damaged the authority and originality of the sunflowers, and removed their “aura” to a mythical region associated with the cult of genius, as Walter Benjamin described in his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, but many visitors will nevertheless flock to the National Gallery in the next few weeks. The appeal of Van Gogh’s sunflowers seems more pervasive than ever.

It will be further enhanced by Bailey’s The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln). This is a handsome book, well organised and beautifully produced, its generous colour illustrations fully supporting the original research. Bailey delivers new insights with an absence of fuss. Even those well versed in Van Gogh will find surprises in it.

Flower painting has a long history, but no other flower, Bailey argues, is so strongly associated with a particular artist as the sunflower is with Van Gogh. He painted his first ones soon after arriving in Paris in 1886. The apartment he and Theo shared was in the Rue Lepic, a steep road that leads up to the top of Montmartre. At that time, it had three windmills on its summit, allotments on its slopes and, among the vegetables, a scattering of flowers. Initially, sunflowers appeared as small details in Van Gogh’s landscapes. Then in 1887, in a series of four oils, he made a close study of them, discovering the Fibonacci spiral in the whirling pattern of their seeds, and using their cut heads as a form of still life.

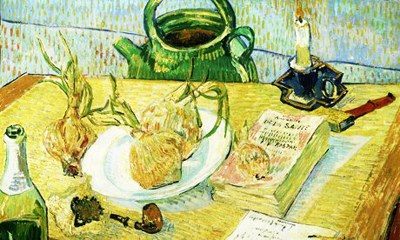

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, 1889. Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Flowers had dominated his output during the summer of 1886. Theo reported to their mother that Vincent was receiving a fresh delivery of flowers every week from friends. One of these may have been Ernest Quost, who specialised in flower pictures, lived nearby and had a garden. The work of flower painter Adolphe Monticelli, who died in that year, remained an inspiration to Van Gogh, as did Edouard Manet’s still life of peonies. Yet his love of flowers had to connect with his interest in progressive ideas about painting. Having previously known little about impressionism, he had arrived in Paris in time to see the eighth (and last) impressionist exhibition. He has also met leading artists through Theo, an employee of Boussod, Valadon and Cie, one of the major outlets for modern pictures, at a time when Paris was the centre of the art world. In Vincent’s mind, nature and art were companions. “Always continue walking a lot and loving nature,” he told Theo, “for that’s the real way to learn to understand art better and better. Painters understand nature and love it, and teach us to see.”

But it was in Arles that the great sunflower period began. And it coincided with his move into a small yellow house on the edge of the square. He got the landlord to repaint it so that the outside walls became the colour of fresh butter and its shutters a rather hideous green. Inside, the red-brick floors were offset by white-washed walls. It was five months before he could move in, but it inspired his great plan. He told Emile Bernard: “I’m thinking of decorating my studio with half a dozen paintings of sunflowers.”

What pushed him into action was the imminent arrival of Paul Gauguin. Wanting to impress his friend with new work, he started painting on 20 August 1888. He sustained himself with coffee and alcohol, and within six days had more or less completed four pieces. One of these was destroyed in the second world war and another, in a private collection, is not well known to the wider public. The other two are those that will hang together for a while in London, and they are among the most famous paintings in the world.

“Arranging colours in a painting,” Van Gogh wrote to his sister Wil, “to make them shimmer and stand out through their contrasts, that’s something like arranging jewels or designing costumes.” He had, by this date, been painting for only seven years, since the age of 27, prior to which he had tried to teach, preach, sell paintings, then books. But now he had fanatical concentration and a confident grasp of his medium. He wanted a similar decorative strength to that which he admired in Japanese prints, in which everything is related, not in depth, but to the picture surface. And he quite often used a “cloissonist” line that, as in cloisonné enamel or stained glass, is used to separate one colour from another, or to reinforce form and contrast. So pleased was he with his sunflower paintings that he hung two in Gauguin’s bedroom, to greet him when, after a delay, he arrived on 23 October 1888.

Bailey is an excellent guide, not only to Van Gogh’s technique, but to the intense two-month collaboration between the painters that ended in disaster. There were, in Van Gogh’s words, “excessively electric discussions”, from which both men sometimes emerged “with tired minds, like an electric battery after it’s run down”. Their views about art clashed, and so did their personalities.

Courtesy of Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Courtesy of Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

However, the final argument, which led to Van Gogh cutting off the lower half of his left ear, may have had an additional cause. Bailey is the first to detect the clues provided by a painted envelope, addressed to Vincent, placed at the fore of the table in his Still Life with Drawing Board, Pipe, Onions and Sealing-Wax (1889). The writing on the envelope imitates Theo’s hand. The postmark shown, with “67” encircled, identifies a post office in Place des Abbesses in Paris, close to Theo’s apartment. Another postmark over the stamps – “Jour de l’an” (New Year’s Day) – was that used in France from late December. And, finally, the “R”, an abbreviation for recommandé (registered), suggests that it would have contained the 100-franc allowance that Theo regularly sent his brother. If received in late December, this would have been shortly before the tragic cutting of his ear, and it would have been shortly after Theo got engaged. News of the engagement would have triggered in Vincent fear of losing his brother’s emotional and financial support, both of which were vital to his life and work.

“He felt everything, poor Vincent,” said Père Tanguy from whom Van Gogh had bought his paints. He never suggested that the sunflower had any religious meaning for him, though it is customarily associated with humanity’s love of God, or Christ. But he did link it on two occasions to gratitude. He admits in one letter: “My paintings are … a cry of anguish while symbolising gratitude in the rustic sunflower.”

SOURCE: The Guardian