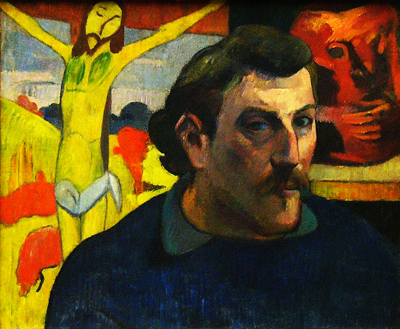

Paul Gauguin, “Portrait of the Artist with the Yellow Christ” (1889), oil on canvas (via Musée d’Orsay)

Posthumous Prognosis for Supposedly Syphilitic Gauguin, via His Teeth

by: Allison Meier

March 2014–It’s long been believed that painter Paul Gauguin was wrecked by syphilis when he died in the Marquesas Islands in 1903, but thanks to some old teeth thrown down a well, he may posthumously be given a cleaner bill of health.

As Martin Bailey reported for the Art Newspaper, researchers with Chicago’s Field Museum analyzed four dislodged teeth that were found in a well in an archeological dig near the hut where Gauguin’s lived from 1901 until his death. The teeth were discovered inside a glass container, along with some painting supplies, like a brush made from an island fruit and a coconut shell still stained with pigments. Since the teeth are pocked with cavities, and people in the Atuona village didn’t eat sugar in that era, they were immediately suspected as European; a later DNA test comparing the dental remains with the teeth of a grandson of Gauguin showed a 90–99% probability.

Gauguin’s teeth (via the Art Newspaper)

But the tests also revealed something else: a lack of mercury, the common treatment for syphilis at the time. This doesn’t mean definitively that Gauguin is in the clear from “the pox.” As Gauguin expert and art historian Caroline Boyle-Turner told the Art Newspaper, “The fact that no traces of mercury were detected suggests that either Gauguin did not have the disease, or that he was not treated for it.”

As a note, side effects of the mercury treatment, according to Harvard’s Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics, include ulcers in the mouth, throat, and on the skin, neurological damage, death, and, yes, tooth loss, although presumably said teeth would be contaminated with mercury unless they were extracted pre-treatment. (Story goes, it was a Parisian prostitute who gave Gauguin the disease, although that’s still debatable.)

So, why would anyone care? Such posthumous revelatory diagnoses are not uncommon for the famous, including European artists of the 19th century, who lived at a time when epidemics were widespread, but medicine to combat them was still being developed. Other artists to get an afterlife prognosis include Seurat, who was long believed to have died at the age of 31 from pneumonia, but may have actually been struck by diphtheria. Back in 1962 the descendants of Toulouse-Lautrec turned down some persistant doctors who wanted to exhume the dead artist’s body in order to analyze the ailments of the notably small-statured artist. Despite the lack of physical evidence, Toulouse-Lautrec has since been determined as having a genetic disorder known as pycnodysostosis, which has taken on the name of “Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome.” What killed him at the age of 36, however, is widely accepted to be alcohol — and, yes, syphilis.

To be fair to Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin, and other artists believed to have been afflicted by syphilis, such as Manet, in the 19th century in some parts of Europe, 10% of men had syphilis, according to the London Science Museum. The sexually transmitted infection still carries something of a stigma, and that taint is part of why it was such a problem in the 19th century. And while it might seem irrelevant to their art, it is helpful in highlighting an underdiscussed health crisis of a particular time.

As for the teeth: after the research was conducted, they were given back to the mayor of Atuona for display at a Gauguin museum located near his old hut, where he may or may not have spent his last days on the island gripped by one of the 19th century’s most devastating diseases. SOURCE: Hyperallergic.com