Betis Mandukit:A Comparative Analysis of the Works of Wilfredo Layug

and Boyet Flores

by: Sherwin Altarez Mapanoo

October 2015–When one mentions the district of Betis in the town of Guagua, Pampanga, the first thing that most likely comes to mind is woodcarving. It is an art that is as old as the history of the town itself and a skill that has been passed on from generation to generation, unveiling the wealth of the locals’ creativity and many facets of their culture.

Betis remains to be the furniture-making and woodcarving centre, not only of Pampanga, but of the entire Luzon. Betis furniture, in particular, is recognized by many as “export quality” and “world class.” The eclectic mix of local and European aesthetic sensibilities has appealed to international buyers for it gives both Oriental and Western appeal. If you happen to pass by the Olongapo-Gapan and Bacolor-Guagua Road, you’ll notice a long stretch of shops and showrooms displaying wood furniture and sculptures of religious icons made by local carvers of Betis, most of them from Brgy. Sta. Ursula. Old folks coming from this barangay are believed to be the pioneers in the tradition of pamandukit (woodcarving) and pamaganluagi (wood working) in the Kapampangan province.

In this essay, the author compares some of the works of well-known contemporary woodcarvers (mandukit) namely Willy Layug and Boyet Flores, and determine how they were influenced by master-carver Apung Juan Flores, while also reflecting on the development and state of the woodcarving tradition in Betis.The following aspects are taken into account and examined: artists’ background; subject matters or themes; styles and approaches; materials and tools; techniques and process of production; and other important issues such as art patronage and market.

Tracing the Roots: The Woodcarving Tradition in Betis

It is said that all art exists in history, and every art object is a product of materials and intentions that mirror a particular time and place. Hence, studying an art tradition necessitates a look into the context. Like any other traditions in the locality, the Betis’ carving tradition has been influenced and shaped by socio-economic and historical developments over the past centuries, the most notable of which is the avalanche of Western influences during the Spanish colonial period.

Historians say that the industry is more than five centuries old. Initially, some writers thought that it was just a recent phenomenon – that it only began when Apung Juan Flores introduced the art to the townsfolk in the early 20th century. However, material evidence disproved this initial assumption. Historians later discovered that there are remnants in some old bahay na bato in Betis, confirming that the art and

Century-old Spanish documents from the National Archives also reveal that the tradition is even farther back. Based on old accounts, “the Adrillanos and Nuguids as well as Davids, who already owned woodcarving workshops in the 19th century, were well- known because of their export-quality dukit” (Banal, “The Town of Betis”, par. 10 ). In fact, even before the Spanish colonization, the locals of Betis were already recognized as blacksmiths, carvers, ship builders and carpenters.

When Betis became an encomienda in the 1770s, the town became a melting pot of economic trade and cultural exchanges and, as a result, the locals were introduced to Asian and European influences. The Betis people embraced and later on appropriated these foreign aesthetic sensibilities in furniture-making while using indigenous materials or woods that were readily available locally.

Contrary to popular belief, however, the first furniture carvers in Betis did not originate from Betis. It was first introduced by Chinese immigrants who were commissioned by the Spanish friars to build and design churches and make wooden church furnishings. The Filipinos became apprentices of the Chinese who taught them in creating the early rebultos and retablos in the town.

According to Prof. Ruston O. Banal of the College of Fine Arts in University of the East, “The Chinese artisans were masters of this craft. Copying from prints and catalogues taken by the friars from Spain, these artisans who later became permanent dwellers in Betis taught the rudiments of wood carving through imitating printed images. The indios, who were probably great imitators, later developed their own” (“The Town of Betis”, par. 7). The influences of the Chinese were manifested in Betis’ carving tradition. Pieces made during the 17th century have touches of Chinese design, while later 18th century pieces are recognized for having ornamented designs.

The tradition further bloomed at the time of the opening of the Suez Canal in the 19th century. Due to active economic trade, the furniture-making became a profitable industry. Local carvers began making a wide variety of wood furniture and decorations, including sala sets, beds, tables, and many others, catering to both local and Betis carvers got their inspirations from Western furniture designs which were brought back in the country by ilustrados who were able to visit Europe. Betis furniture also absorbed influences from various cultures that made contacts with the town.

Rococo forms and other European trends and American designs became prominent as time went by. Until now, these aesthetic sensibilities are evident in the works of contemporary mandukit of Betis. Artists’ Background: “It Runs in the Blood”

At present, the most acclaimed and recognized wood carvers in Betis are Willy Layug and Boyet Flores. Both of them are highly prolific and versatile, and famous for their specialized skills in working with wood that is not an easy medium to craft and manipulate. They both acknowledge the fact that there is little room for errors when carving wood, and precision is “a must” in making intricate details.

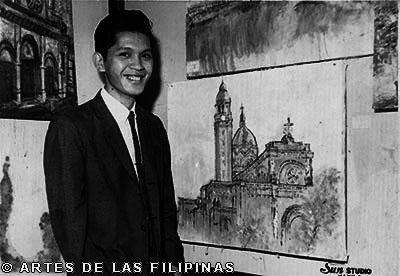

Willy Layug

Boyet Flores

Woodcarving requires specific skills that need to be developed through the years, and both of them can attest to that. hails from the town of Guagua. Born on December 5, 1959 in Betis, Layug was a son of a matenacan dadaras or a boat maker. During the Spanish occupation, the boat makers of Betis were acknowledged because they were said to be the predecessors of the builders of the early galleons. On the other hand, Mang Boyet is a descendant and nephew of Apung Juan. He was born in 1967 in Brgy, Ursula, Betis. Hence, it can be assumed that their inclination to woodcarving runs in their blood and has its roots in their family’s past occupation.

Another notable commonality of Layug and Flores is that they got the opportunity to become apprentices of Apung Juan during their teenage years. Both sculptors were introduced to woodcarving at a very young age and influenced to a great extent by the master-carver, in terms of their techniques, process of production and themes.When he was an apprentice, according to Mang Boyet, his grandfather would allow him to work on decorative floral sculptures which can measure up to a meter in length and width. “He introduced me to carving bulabulaklak because it’s big. I was usually tasked, along with other students, to work on specific portions of the entire work. It taught me to be extremely patient because attention to detail is important,” he said. Amateur carvers under the tutelage of Apung Juan were also taught in making rebultos or religious icons. According to Layug, he was initially acquainted with making religious images and giving a “new antique” quality to them. When he was in high school, he became a working student under the apprenticeship of Apung Juan and a certain Pedro Datu. These two masters honed his talent in both drawing/painting and

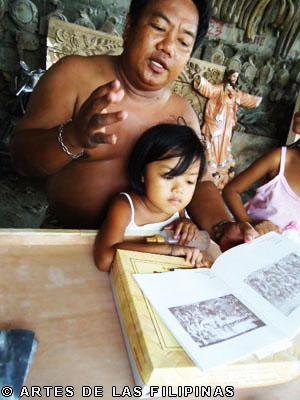

Making reproductions became a good learning experience and training for both artists. As apprentices, Layug and Flores would make copies of religious images with the accustomed iconoclastic representations. The common iconographies included The Holy Family; The Crucified Christ, St. Michael defeating satan, and the like. The catalogues of Apung Juan, according to them, were very significant because they served as their references and prototypes in making rebultos.

Equipped with dexterities in woodcarving, Layug and Flores would later embark on mastering the creative process, either by having formal education or doing research. Their educational background, however, is totally different. Layug felt the need to finish his education and get training and workshops. In 1978, he enrolled in the University of Santo Tomas where he took up Architecture and Fine Arts major in Painting. While studying, he would still accept projects, in order to hone his skills and generate money for his education. His first break happened when he was just 17 years old when he made a bas relief of a replica of Santiago Matamoros at the gate of Fort Santiago. In 1999, he travelled around Europe and visited countries such as Germany, Italy, France, Switzerland, Austria and Poland to observe churches and improve his skills in designing retablo. In three consecutive summers of 2007 to 2009, Layug went to Seville, Spain to study the art of estofado. He spent the whole month as an apprentice under Maestro Arteaga, a famous Spanish sculptor of liturgical pieces.

Unlike Layug, Mang Boyet was not able to finish his studies and didn’t have any formal artistic education. He only relied and developed his skills from his hands-on training with Apung Juan. However, he continued on doing research after his grandfather’s demise in 1992. “When Apung Juan died, I did my own research. Until now, I still get inspiration from his piyesa which I inherited. I’m happy to continue my grandfather’s legacy. It’s because none of Apung Juan’s children knows how to carve,” he stressed.

Themes and Styles: Folk vs. Western

The influence of Apung Juan is highly evident in the themes or subject matters of Layug and Flores’ works. Their usual subject matters can be divided into two categories: (1) religious or ecclesiastical and (2) non-religious.

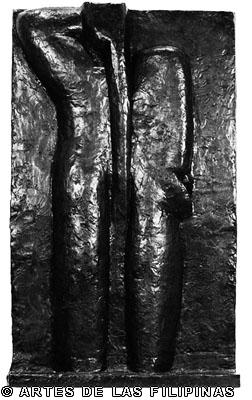

Religious themes include images and figures of saints (santo, malasanto or rebulto); wooden karo (carroza); altar; retablo; and other church furnishings. Non-religious themes are utilitarian in nature and for decorative purposes. These include: furniture, portrait/bust, and nature (animals, flowers, plants, etc.).

Related to the common themes is the artist’s style. Mang Boyet has basically appropriated Apung Juan’s designs, a combination of folk and European styles such as rococo, baroque and classical. His works are mere replications of Apung Juan’s masterpieces. The Baroque influence, in particular, can be seen in the wooden karos that he designed.

Take for instance the carroza that Mang Boyet built for a church in Taysan, Batangas. In this particular work, the sculptures have a dynamic movement. The religious icons are spiralling around a central vortex. There are also multiple ideal viewing angles. Rococo can be also seen in the artist’s love for details at the base of the carroza. Similar to Apung Juan, Flores’ religious imageries are based from religious pictures and icons from Europe’s post baroque period.

Mang Boyet still makes religious icons such as Santo Nino, Jesu Cristo, and the like, with the customary iconoclastic representations. These santos copied from Apung Juan’s previous works, are intended to be displayed in home altars.

Folk sensibilities are apparent in the ornamental motifs and local design patterns known as: (1) bulabulaklak (floral) and (2) kulakulate (design simulating vines).

Kulakulate by Flores

Bulaklak by Flores

Such folk designs can be seen not only in Betis furniture, but also in the details in retablo, altar, and carroza designed by Layug and Flores. They use similar patterns (templates) that are made of paper to trace the basic outlines, designs and appearance of the detailing and engraving works.

Patterns used by Flores

Patterns used by Layug

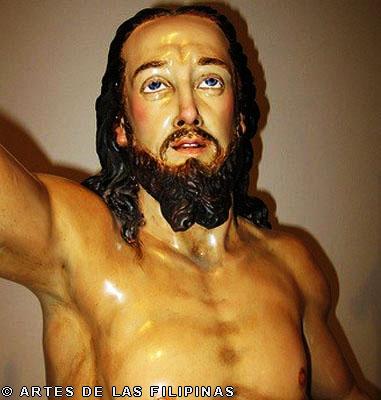

As regard to sculpting religious icons, Willy Layug follows the classical and neo-classical tradition, with works expressing profound emotions, incorporating different European styles in ecclesiastical sculpture.

Resurrected Christ by Layug, 2010

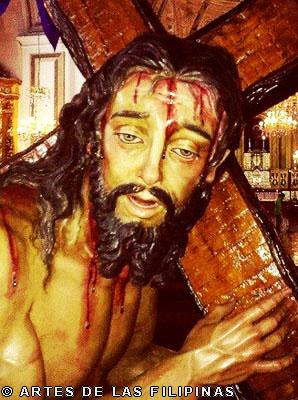

Pasion de Jesus by Layug, 2011

There’s a sense of romanticism in his works. His style veers away from traditional formality. Instead, he carves images

that are dynamic, satisfy the romantic spirit, and glorify intense feelings and emotions.

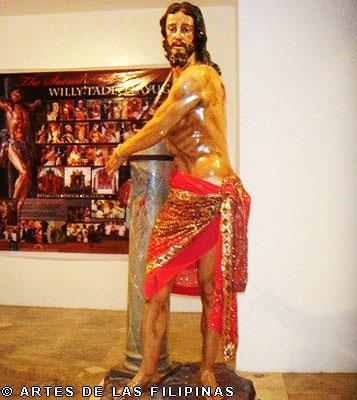

Layug is also known for making sculptures with contrapposto, which is an Italian term for human figure sculpture with a counterpoise and standing with most of its weight on one foot. In this classical approach, the figures have a much more dynamic and relaxed stance.

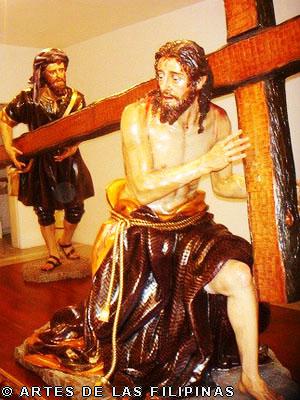

Cristo de la Columna by Layug, 2010

Simon de Cyrene by Layug, 2010

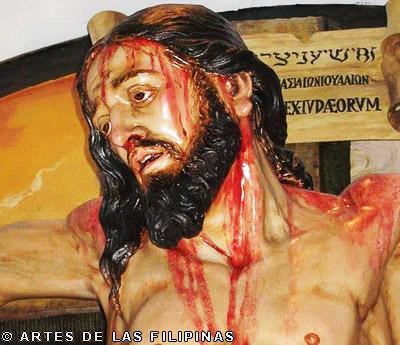

His works can also be categorized as “hyperrealist.” Layug gives utmost importance to every detail. There’s an attempt to (re)create an image as close to the real life model as possible. He creates sculpted pieces that seem alive in every detail, right down to veins, tears, eyelashes, discolorations on skin, dripping blood, etc.

Portrait Bust

Christ in Retablo, St. John Parish, Labo, Camarines Sur

Materials and Tools: Traditional Vs. Modern

Both sculptors are utilizing wood as their primary material. Local and imported woods are used. Lumber is usually sourced from trees cut in Magalang and Arayat, as well as the nearby province of Zambales.

Two types of wood are used in Betis – (1) hardwood and (2) softwood. Each is chosen appropriately for specific works. Hardwood is often used for trimmings and furniture but less frequently than softwood. It is typically more costly than softwood. One example of hardwood is narra. Softwood, meanwhile, is widely used as the material for making santos, woodware for building (homes) and also furniture. Baticuling is a popular softwood among Betis carvers.

For furniture making, commonly used woods used are: rattan, kamagong, narra, mitla, balacat, balanti, balete, yakal, and bangcal. For santos and other carved images, woods that are readily available are germelina and baticuling.

Aside from woods, Layug uses clay, terra cota, wires and cement, but these materials are only utilized in the stage of designing and cast-making, and not in the actual woodcarving process.

When it comes to tools, traditional and modern/mechanized tools are used by both sculptors. Although hand-held power tools are utilized to improve their carving efficiency and simplify the carving process, they still use traditional equipment such as mallets, gouges and chisels, as they are better at carving inlays and engraving. Flores particularly relies heavily on traditional tools such as mallets and chisels, carving knives, saw and sandpaper.

Mallets and Chisels

Electric Sander

Sandpaper

Apart from traditional tools, Layug makes use of a sophisticated computerized carver which, according to him, is an equipment designed to double productivity due to the increasing demand for his works.

Techniques and Process of Production

Layug and Flores have different methods of making wooden sculptures. Because he has the financial means, Layug relies greatly on mechanized tools. On the other hand, Flores generally utilizes traditional woodcarving tools.

Designing and Cast Making

The process of production usually starts with designing. Layug begins by making a clay maquette (model) using traditional clay modeling tools and methods. He uses this as his primary model. Boyet no longer does this, since he already has existing models to copy.

Clay modelling is an age-old technique taught by Arteaga that is fairly new to Layug. He said that the clay-modelling technique is much more effective because it serves as guide to model the actual sculptured piece, hence reducing room for errors.

Next step is cast making. The cast, which is usually made from cement, terra cotta and wires, will be copied by the machine.

Clay Maquette

Cast

Wood selection is also equally important. It is a matter of personal preference and availability. According to Mang Boyet, a good carver must have a good understanding of the type and nature of wood, such as its hardness, grain structure and direction.

Carving, Detailing, Sanding

After selecting the appropriate wood, the carver will proceed to carving. Unlike Flores who does everything manually, Layug utilizes of a computer controlled router (CNC) machine to do the initial stage of carving. The machine is capable of replicating

any three dimensional woodcarving through the rough out and detail stages.

Afterwards, they will proceed to detailing or working on finer details. For the next stage of carving, hand-held tools such as mallets and chisels are strictly used. The main goal here is to carve the chunk of wood as close to the clay model as possible. This is followed by sanding and finishing. Both of them use electronic sander to smooth wood or wood finishes.

Sample of unfinished santo by Layug

Painting

What follows after is the meticulous process of painting the wood. Layug and Flores have their own respective methods of painting. Flores only employs traditional painting method using wood paint, lacquer or varnish. Layug, on the other hand, follows the process known as “encarna”. This process is a tedious undertaking and needs a lengthy procedure using materials such as: cola de kunejo, stucco, ducco and processed by estofado (quilting) and dorado (gilding) (Banal, “Willy Layug”, par. 33). He also learned this technique from his apprenticeship with Arteaga.

According to Layug, painting a wooden sculpture is a seven-way treatment. Instead of using sanding sealer before the final coating, Layug follows the “antigong tekniko” where various layers of paint are employed on the icon’s surface. The piece is

then rubbed with abrasives to make it as smooth as silk (Banal, “Willy Layug”, par. 33).

The primary rationale for this technique is to hide the pores of the wood in order to prevent any breakage, hence making the completed sculpture much more sturdy and long lasting.

When it comes to gilding, real gold leaf is usually used. This technique is known as estofado which basically involves the application of gold leaf over the surface before it gets painted with the chosen color. The surface is then delicately scratched or incised with design to reveal the gold underneath. The estofado technique is an expensive finishing method so it is not surprising that only the wealthy clients and patrons such as

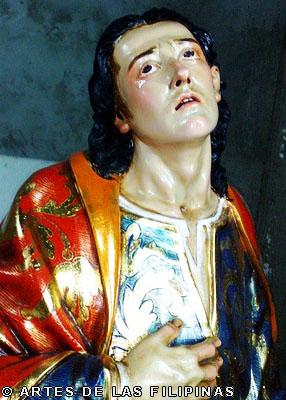

San Juan Evangelista by Layug, 2010

Retablo of Chapel of the Holy Guardian by Layug 2008

Art Patronage, Market and Other Issues

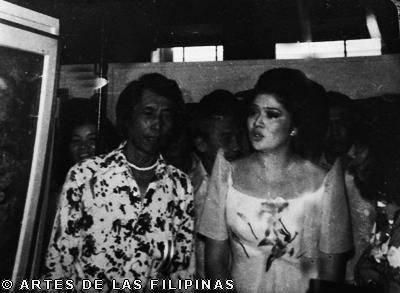

In Betis, the church as an institution and art patron plays a big role in the continuous proliferation of ecclesiastical sculptures in the town. Layug’s main patron is the Roman Catholic Church. Although Flores gets commissioned by the church, he primarily caters to private individuals and families. Layug is much more favoured by parish churches from all over the Philippines to create extravagant retablo and other church installations. Such projects amount anywhere from hundreds of thousands to

millions of pesos, from works on churches and on private referrals.

Layug started to become popular in the ecclesiastical art world when he decided to focus on retablo-making. In 1997, he met Archbishop of Lingayen-Dagupan and established a long-time friendship. Since then, he has been receiving expensive commissioned projects for chapels, parochial churches and even cathedrals. To cite a few, Layug has done major retablos for main cathedrals such as The Cathedral of St. Joseph in Nueva Ecija; the St.John Cathedral in Lingayen-Dagupan; San Sebastian Cathedral in Bacolod; and the Cathedral of the Immaculate Concepcion in Urdaneta, Pangasinan. (Banal, “Willy Layug”, par. 23). Most recently, he was tapped to make religious sculptures for the pastoral visit of Pope Francis last January 2015.

Increased demands for Layug’s works led to increased profits. In 2006, he was able to open his showroom Betis Galleria along the Gapan-Olongapo Road, Pampanga. At present, his woodcarving business generates jobs for 29 people, mostly relatives, friends and neighbors.

Notably, Layug does not only get support from the church, he has also gained recognition from members of the art world and the government. Art players such as curators, writers and gallery owners, have put Layug in the pedestal, recognizing him as

“maestro” (genius). Unlike Mang Boyet who is “relatively unknown” to people outside of Betis, Layug is quite popular in various parts of the Philippines because of his retablos. Several articles and press releases have already been published about him. He has also exhibited his sculptures in art galleries and museums, not only in Pampanga, but in Metro Manila as well. In March-April 2010, Layug mounted a solo exhibit entitled “The Sacred Art of Willy Tadeo Layug” at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. He was also invited as a participating artist in the exhibition “El Guernica: Deconstrucción” organized by the Embassy of Spain in the Philippines and the Ayala Museum in June-August 2011. Layug’s contemporary sculpture is an interpretation of Pablo Picasso’s painting,

Here, we can clearly see the primary function of the art world “to define, validate, and maintain the cultural category of art.”(Irvine, par. 1) Art is at all times defined in terms of the relationship of people and objects to certain established institutions. As such, given the validity from and support of “art institutions,” Layug’s works are no longer seen as “crafts,” but “arts” instead. One testament of this is the “Presidential Medal of Merit” given to Layug in 2009 by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo for his “exceptional achievement in art.” This is the highest award a Filipino can receive from the President. It is (loosely) awarded to individuals and groups “for service to the President or for achievements that, in the Chief Executive’s judgement, bring honor to the country.” He has also received other accolades which further boost his reputation as a leading ecclesiastical artist in the Philippines. In 2002, he was awarded Most Outstanding Kapampangan for Ecclesiastical Art; and in 2005, he was also awarded as Outstanding Guaguaño for sculpture and ecclesiastical arts.

In contrast, Mang Boyet doesn’t receive that much recognition because of his limited access and affinity to art institutions. This only shows that local artist’s works will remain understated without the support from the members of the “art world” which remains to be elite-oriented and predominantly defined by players such as art patrons,

including the church, critics, and politicians.

REFERENCES

Banal, Jr. Ruston. “The Town of Betis: Woodcarving Its Place in Art and History” UE

https://www.ue.edu.ph/manila/uetoday/index.php?nav=24.htm&archive=200702

______________. “Willy Layug: His Life and Art With Betis Galleria.” Published in Jul

21, 2008 . http://betis.wikifoundry.com/page/Wilfredo+Tadeo+Layug

Irvine, Martin. Institutional Theory of Art and the Artworld (Overview).

http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/irvinem/visualarts/Institutional-theory-artworld.html

Tana, Ricky. “Maestro Apong Juang Flores: His Life and His Art” Sulyap Kultura Series

Official Website of Willy Layug: http://www.willylayug.net/

Sherwin Altarez Mapanoo is a multidisciplinary writer, researcher, and nomadic visual ethnographer. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Art Studies (Interdisciplinary) from the University of the Philippines and a double post-graduate degree with distinction in International Performance Research and Theory of Art and Media, Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of Warwick, United Kingdom and the University of Arts, Belgrade, Serbia, respectively under the Erasmus Mundus programme.