Repaso ng Tres Personas, Imagining Identity,100 Self-Portraits by Filipino Artist Exhibtion, Finale Art File (2011)

Noel Soler Cuizon’s Gesamtkunstwerk and Everything in Between

by: Christiane L. de la Paz

April-May 2017—The public exhibition of Noel Soler Cuizon’s works began in 1987 when he was a member of Hulo, a group of alumni students of the Philippine Women’s University who explored non-traditional Western materials. Freeing the hand from the brush and utilizing it in other manual aspects of works led him to work with wood assemblages which he composed in a structure of multi-frames that overlapped each other and accompanied with painted cut-out figures, thus, engaging the viewers to interact with the contents of his art pieces. His works were later referred to as interactive wood assemblages. In 2004, he began exploring performance art as a medium to expand on the interactive model of his early works as well as to define the symbiotic relationship between the message and motivation of all his other works. Markadong Bayani (2004) was his first public engagement with performance art in Manila which he mounted at the Kanlungan ng Sining in Rizal Park. Reenacting the execution of Jose Rizal infront of his monument, he and Crisanto de Leon, his collaborator, appropriated the idea of Christ falling three times when he carried his cross. In this interview, Cuizon has done a sensitive job of taking the readers to the impulsion of his artistic hunt beginning with his maternal grandmother, Natividad Fajardo and his aunt, Brenda Fajardo. He also provided some very welcome and interesting anecdotes on his art professors in the Philippine Women’s University, his undergraduate thesis, his early years as an exhibiting artist at Hiraya Gallery, his teaching career and how all these nascent experiences translated into his art. He also passed on some of his views about how his assemblages should be regarded, the relevance of curatorial reviews, the frills and thrills of an artist, among several others, striking a balance between too much and too little editorial intervention. One is led to believe that his art practice typifies the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork).

What projects did you engage in after graduating from the Philippine Women’s University in 1987?

I went full-time as a freelance artist/painter for the most part. I also worked on various projects with some Theater Productions. In PETA, I was part of NGO, Ang Dagang Patay by Nonoy Marcelo and the re-staging of Aurelio Tolentino’s Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas. At the Cultural Center of the Philippines, I was involved with the Kwentong Lukayo and at the PASILAG, the restaging of Kwentong Lukayo and Sumpa ng Diwata. I joined their Set and Costume Design Teams. Occasionally, I held informal drawing and painting workshops through the outreach programs of several cultural groups. I was invited by Ayala Museum to start with its Escuela Sa Museo program in 1995. I stayed with the institution until 1998. I also put up a catering business with cousins and friends that provided artists and art centers a different approach to artists’ receptions. We would do thematic cocktails for exhibition openings and other art events.

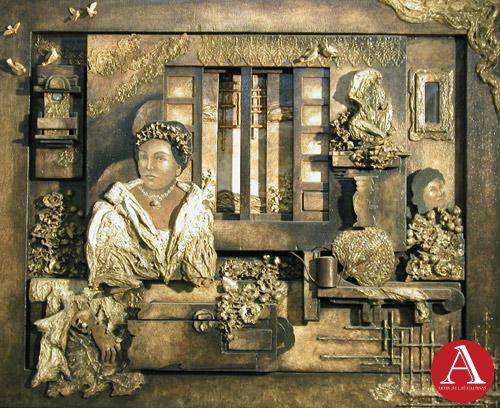

Kasal (1993)

What was the status of the art scene during the mid-1980s? Who were your contemporaries?

The mid-80s up to the early 90s was like a Renaissance of sort. After the EDSA Revolution, there seem to be a fermentation of new creative expressions that brought young artists together. This is in congruence with each other’s search for national identity and new expressions. There were a lot of biennales and international shows interested in Pinoy art. The scene was not so market-driven then and the collectors didn’t just acquire artworks; they conversed with artists and discussed art processes and theories. They tried to understand where the artist was coming from. Most of them became good friends even after they stopped collecting. We, the young artists enjoyed doing art and exploring new approaches in our craft. We were not so much concerned with our financial advancement. I was more concerned about peer validation though (laughs). Romantics as most of us were, we, became more interested in exploring other forms of artistic engagement through community involvement, advocacies and informal art education. My contemporaries are Karen Ocampo Flores, Mark Justiniani, Elmer Borlongan, Antonio Leaño, Yasmin Almonte, Salvador Alonday, Alwin Reamillo, among others.

Nuestra Señora de los Sufridores (1994)

Pasaporte (1995)

What made you decide to pursue Fine Arts in college?

I have always been interested in drawing and other creative stuff so I thought that Fine Arts was the right course to take up after high school. On the outset, I had the impression that art was purely about aesthetics until I entered art school and became aware that it’s not just about honing your skills. You have to learn about translating perception, improving visual communication, and understanding history and theories. Since then, it has always been my concern to strike a balance between theory and practice. I think I was also inspired by my lola and aunt, Brenda Fajardo, who was then very active in theater, visual arts and other creative activities. Their artistic energies were nakakahawa. Growing up with two creative minds and having been exposed to various creative endeavors became an impetus for my future artistic pursuits.

My father, on the other hand, was very much against my decision to take up Fine Arts after high school so I enrolled in Architecture instead. My freshman year was a disaster; the rigidity of instruction and discipline particularly on mechanical drawing didn’t appeal much to me. When I shifted to Fine Arts years later, I saw myself veered towards the same direction that I had refused to accept before. The irony of it all is that every work in my succeeding years in art school tagged on the visual organization of design patterns, grids and structures akin to mechanical drawings.

Si Don Andres May Pag-Asa at ang Pagbabalik ni Bernardo Carpio (1996)

Moro y Cristiano (1996)

Let’s talk about your student years. Who were some of your memorable professors in Fine Arts?

In my formative years, there were Ibarra de la Rosa, Angelito David, Paul Dimalanta and Renato Ong, Pandy Aviado, Boy Rodriguez Jr., Lito Mayo. Iba’t-ibang schools of thought ang pinanggagalingan nila. I think we had the best roster of teachers then. I learned a lot from all of them with regard to techniques and visual perception. Roberto Feleo was my undergraduate thesis adviser so he has influenced me a lot. Informally and vicariously, I was also influenced by the social realists like Antipas Delotavo and Egay Talusan Fernandez, who were both graduates of PWU and to a great degree, the late Santiago Bose.

Occasionally, I would sit-in at Angelito David’s watercolor class. Since I followed a new curriculum when I enrolled at PWU, I wasn’t able to formally enroll in his class. But I learned a lot of techniques from him, obliging myself to follow all his instructions. But he didn’t realize that I was not legitimately enrolled in his class until the last quarter of the term. I never submitted any of my finished works for assessment and would just listen to the evaluation of the works of other students in his class. It was a vicarious learning experience.

Walang Kupas (1996)

Sa Ayaw Makabatid (1996)

What did you learn from Ibarra de la Rosa?

Ibarra de la Rosa trained us to embrace discipline which we obtained through hours of studio work. I think he did put more weight on studio routine. We would learn the rudiments of painting more than scrutinized concepts and theories of art. He was also quite strict with deadlines. I remember how he would give us the same time frame to finish a 3’x3’ canvas and a 1’x 1’ canvas and how he would occasionally throw half-baked plates outside the window. It was unthinkable at the time and very taxing for a lot of us students. I didn’t like the severe directives then but looking back now, I must admit that it was imperative to studio practice.

Hudyat (1996)

Cofradias (1996)

How about Boy Rodriguez?

Boy Rodriquez taught us all about the concept of play in terms of approaching our form, subject and content. He was very particular with how we understood the intricacies of the medium which included the basic techniques and approaches of printmaking. What I enjoyed most in his class was the limitless possibilities of expressing our ideas through various processes. The exploration even went beyond the traditional mode of instruction wherein we were allowed to break the rules once we’ve had the grasp of them.

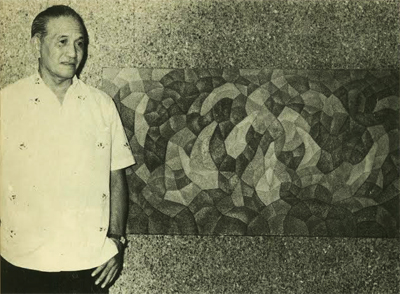

Lito Mayo’s Komersiyalismo (1976) which Cuizon appropriated for the TutoK Kargada show at the Ateneo Art Gallery

In what way, did Lito Mayo influence you?

In the middle of the term of 1981 or 1982, Lito Mayo started teaching at PWU. I was transferred from Ibarra’s class to the new instructor. We were, I think, around eight students, the delinquent ones who refused to follow Ibarra’s instructions (laughs). Of course, I was so frustrated at first but when I met Lito Mayo and started holding classes with him, everything became a journey in exploration and experimentation. For the first time in art school, I felt so motivated to work and felt alive! I made a series entitled Dream Saga in Lito’s class and he was very encouraging. It was the first of that series. I lost everything after I graduated. Now, if Lito passed away in 1983, that class must be before the summer of that year. When summer came I even had dreams of Lito that I was conversing with him under the trees sa vacant lot ng Fine Arts in PWU. He was standing beside his motorcyle in his usual black leather pants and jacket. The words he was uttering were inaudible. Mga three nights ko siyang napapaniginipan. Then days later, I went to PWU to check my grades only to find out na ililibing na siya in Batangas. I lost a teacher who had always encouraged me to explore creative possibilities. Lito did not influence me in terms of style but he guided me towards artistic exploration. A year before I had my heart attack, an aunt’s friend gave me a Lito Mayo print which I was able to sell to an old friend after my angioplasty to cover my medicine expenses. It was against my will and among other works I thought that maybe Lito was trying to tell me, “O ayan ah! Nabenta mo work ko, pambili ng gamot mo.” Si Lito Mayo, nung estudyante pa kami lagi akong binibiro,”Huwag ka masyadong seryoso, bata ka pa!” He was like a barkada teacher to me.

In 2008, I was part of the show, TutoK Kargado at the Ateneo Gallery curated by Bogie Tence Ruiz. He asked us, participating artists, to create a visual dialogue between contemporary Filipino artists and the modern masters in the collection of the Ateneo Art Gallery. The show examined nationhood, modernism, critical self-recognition, political complexity and proposes that art practice comes with an inseparable charge, a context, an implication that cannot be distilled away into absolute form but has to be grafted and manifest by and in such form to fully address the era it came from. My response to the curatorial plan was to situate the works of Lito Mayo and Brenda Fajardo from the gallery collection in a discourse about the nature of influences. These two great artists have influenced me in my artistic journey so I envisioned an installation piece that will simulate a scene where I would be paying homage to them. And as if to continue my “Dream Saga” series for Lito Mayo’s Techniques class, the installation took a facsimile of fragments coming from a dream. The material set up imitated a venue where I would be in conversation with my two masters/ mentors. In my assigned space, a long table and two wooden chairs were hanged upside down from the ceiling and another chair was positioned on the floor facing a wall where their works were to be installed. I photocopied their other artworks that were not part of the Ateneo Art Gallery collection and had them laminated. I hanged the plastic-coated estampitas into mobiles of sort to create the flow of a suggested tête-à-tête with them regarding their artistic explorations – represented by a range of their creative outputs.

X (1997)

After A Hundred Years of Dreaming (1997)

Tell me about your student works.

The early works I did in school were the usual art stuff, the basics, and some “lolo” art as my students label them now when they see: landscapes, still life, portraits and the like. I began exploring new visual idioms when I reached my junior year under Roberto Feleo with the intermediate art subjects that dealt with problem solving in the arts, exploration of materials, developing your own visual language and understanding visual metaphors in artistic expressions.

Anatomy of Displacement (1997)

Correspondence of Ironic Metaphors (1997)

What was your undergraduate thesis about?

My undergrad thesis came about with the challenge put forward by my adviser, Roberto Feleo during our Art Workshop classes prior to the thesis: to explore various possibilities of involving the audience in a dialogue with your work, by means of a format that will entail a totally different method of interactivity. As a response to this visual problem, I wanted to address the normal reaction when you’re confronted with a “Do Not Touch the Painting Please.” instruction commonly seen in galleries. I decided to take the reverse position as the premise of my ‘manipulative’ course of action wherein the audience can literally touch the artwork to arrive at an understanding of the artist’s intention and narratives. My method was to initially set the main theme for the two-dimensional piece and encourage the viewers to manipulate some of the components within the pictorial plane. Upon going through a tactile experience with the artwork, the supposition was that an engagement could be forged to allow different modes of interpretation.

In addressing the issue at hand, I started exploring my visual discourse by creating assemblages of cut-out wooden pieces, multi-layered platforms and found objects. Instead of just establishing the pictorial surface through the formal elements and principles of design, I had to make a decision on how to achieve an effective visual representation while translating the interactive aspect of my mixed media works. The fruition of these possibilities was conceived when, one day, my four year old nephew visited me in my studio and started playing with all the elements of my work left on the floor, which, at that time, I didn’t have a clue on what to do. When I saw him arranging the detached pieces of the unfinished work, the idea of making my artwork interactive was conceived. What if I put pockets and platforms with various cut-out figures where the audience could interchange some of the work’s components or even intervene with the composition? It took me a while, however, to integrate the concept of how I was previously trained to put things together as a painter. So as not to lose track of my direction, I would always follow the creative process that I’ve been accustomed to in handling two-dimensional planes. I would start with the concept, do some rough studies and then proceed with a compre. And as I was just starting to explore this method, I would even make a maquette before working on the actual piece. With this scheme, I was able to achieve both goals of creating an effective pictorial organization and motivate the audience to physically interact with the components of my artwork.

Cerebral Decolonization 2 (1997)

Deconstructing Icons 1 (1998)

What media do you work in?

Through several experimentations and after acknowledging the importance of learning the basics, I was able to develop new ways of seeing things that helped me in translating concepts and narratives through my own visual language. Exploration of non-traditional materials was positioned in understanding how I could effectively articulate my intentions. Medyo mahirap ito kasi I’m not so good in articulating verbally what I wanted to express visually. It has always been a lot easier to illustrate ideas visually rather than talk about them.

My work took the non-traditional direction with mixed media works and interactive assemblage. It was a subconscious application of a child’s play or how I would visually react to stimuli in my younger years. My approach would basically start with how I would handle pictorial composition in a two- dimensional pictorial plane before it evolves into its final assemblage stage. In a way, I’m still consciously following my basic training as a painter. Eventually and as I develop my style and visual language, I became more comfortable with addressing the materials as they were and would directly address the art problematic without reference to my academic foundation.

Deconstructing Icons 2 (1998)

Deconstructing Icons 3 (1998)

What themes did you explore the most?

My works took the direction of engaging in an editorial using visual metaphors that deal with contemporary life: socio- political issues, lessons learned from history and a critical assessment of other cultural issues.

Centennial Jargon (1998)

Auto-Letrato (1998)

What was the first gallery that showcase your works?

I started with Hiraya Gallery in 1988 and I was in its stable until 1998. I had three solo shows there. That’s also where I learned a lot about art practice through the tutelage of the late curator, Bobi Valenzuela. Artists would gather around the venue to discuss everything from visual arts to music to history and theater, philosophy and literature. I also honed my exhibition design skills there also under the mentorship of Bobi Valenzuela.

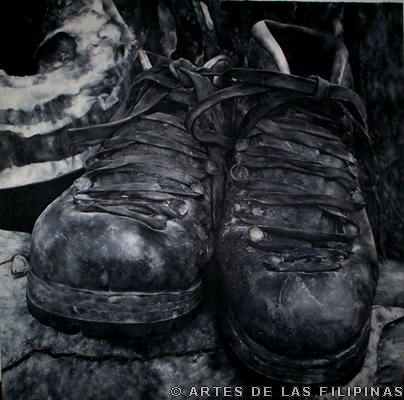

Philippine Star (1992)

Tell me about your first exhibition.

Masaya na mahirap at overwhelming. Where do I start here? There was a call from Bobi Valenzuela to all the artists at Hiraya to respond to the upcoming national election. The curator wanted to mount a show in time for the election, so Christmas pa lang of the previous year, inupuan na namin ng ilang mga artists yung project. My take on this was to do an inquiry and assessment on each candidate and translate my opinions visually into assemblage pieces, the interactive ones. Ang daming conflicting ideas plus dami rin turncoats, lipat ng partido and compromises regarding each candidate’s platforms. I rented a studio space in a remote subdivision at Fairview to finish my series so I had the dailies to inform me about the progress of the “circus.”

Come May 1992, I was informed that the artists did not respond to Bobi’s call. I can’t blame them, para naman talagang circus yung election, medyo magulo in a sense. So hayun, he just mounted my works at the Mezzanine of Hiraya, no fanfare, in fact, wala ngang opening. The collection was just up for viewing. I think my first solo exhibit was not an official one until the press picked it up (laughs). Before I knew it, may interviews na and later lumabas na nga yung mga reviews about “Hugot-Bunot sa Mayo Onse” and my claim to fame of being the only artist to have mounted an exhibit about a national event (laughs). Little did I know na ako nga lang pala ang may responde sa Philippine art scene about the election. I was even surprised when I heard from the gallery that a Japanese collector bought the seven works and later brought it to Paris so my works for that show were never properly documented.

Two weeks after the exhibition run and after the announcement of a new Philippine president, I was invited for a move-over show at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Pandy Aviado, who has been my professor at the Philippine Women’s University and at the time, the Coordinating Center for Visual Arts director of the CCP invited me to have a solo at the Small Gallery with a revised title: “Hugot-Bunot Kinapos.” I had to add four other works and an installation piece of painted ballot boxes, para di kumalog ang mga piyesa sa Small Gallery.

Kasal (1993)

For the ideas of your own exhibitions, how do you try to be unique in concepts and executions?

Ain’t hard to be unique (laughs)! But really, it has never been an issue with me. I believe in collective memory and parallel interpretations so I just follow my thoughts and assess the topics that I want to cover before I work on a piece. I let my creative side take the upper hand and allow visual surprises to take their course (laughs). Seriously, I bleed every time I start with a new work.

Tag-Sibol: In Search of Venus (1999)

Tag-Lamig: Waiting for Spring (1999)

Have you heard of comments that a certain artist has done the same kind of work that you did for a particular exhibition?

If viewers have mentioned before that my works looked like that of other artists, I interpret them now as more like being influenced by certain artists. The character of visual persuasion and predilection comes into play here. Each artist influences one another in so many ways. So even if the initial remarks were “your works look similar to the works of so and so artists;” their comments were dissipated upon closer scrutiny of the pieces. After viewing the exhibition, they would acknowledge later that what I have been doing in my visual explorations were totally different from their references.

Of Cryptic Appropriation and Identity Politics (2000)

When you are in the process of preparing for a solo show, who is the viewer you have in mind?

Students, art aficionados, academicians, critics and patrons. In that particular order.

The Pilgrim Sorcerer (2000)

Do you think a painter can become commercially successful without receiving any award?

I think so. It’s just a lot easier if one gets validation from the establishment.

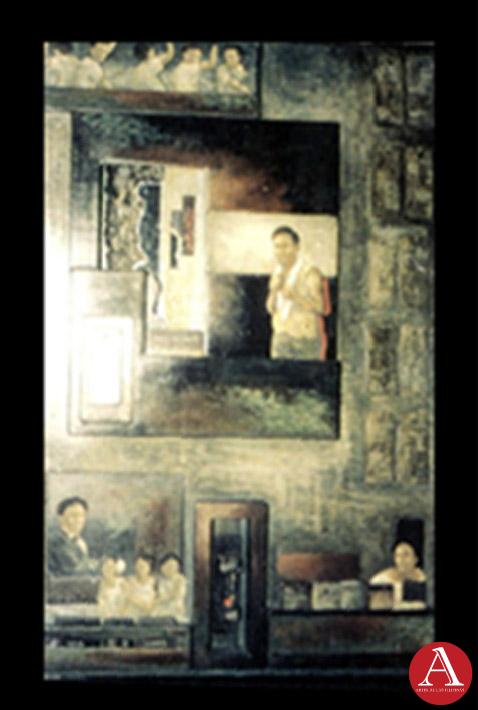

Ang Tala-Arawan ni Mang Idong at Don Juan

I understand that you are an old hand in receiving awards. Do you remember your first painting that won third place at the Hiraya Painting Competition? What is this painting about?

The Hiraya Gallery and Titanium Group Painting Competition was an open call to all Filipino artists but there’s an age limit of forty years old. That year’s winners were Nelson Ferraris, first place, Php 30k, Justo Cascante III, second place, Php 20k and myself in third place, getting Php 10K. Ang Tala-Arawan ni Mang Idong at Don Juan, my entry for the competition talks about the dynamics between constituents in the context of hierarchies inside a very feudal system. It focuses on the human aspect within the social structure. It speaks about the undying loyalty of a servant to his master that started with an anecdote about my maternal great grandfather, Don Juan, taking custody of Mang Idong since he was eleven years old. A remarkable relationship between the two was forged. The latter feeling indebted to Don Juan, continued to serve the family even after the demise of the patriarch and upon the outbreak of the Second World War, Mang Idong decided to stay with the family and had chosen to devote his time to my Lola Naty, who was amongst the other thirteen Fajardo siblings and her two daughters, my mom and aunt, until his last remaining days. I’ve always admired him from a distance as I hear a lot of stories about his unrelenting dedication to our family. The artwork was my way of paying tribute to the man.

In this work, I’ve taken up on the methodology of autobiography and biography as a theoretical model. The interchangeable pieces here were cut-out wooden figures of both Don Juan and Mang Idong, alternately, taking center stage within the social strata, a deconstruction of hierarchies as depicted in the pictorial surface. It simulated a journal and a portrait reminiscent of the olden days brought into play with the colors, tones and texture of the work. The contention here was that perhaps portraiture, which was reserved fo