THE SPIRIT OF THE BABAYLAN

IN THE ART AND LIFE OF BAIDY RICO MENDOZA (First of Two Parts)

by May Tobias-Papa

She is truly mystical. Of herself she declares, “I am as old as the hills and as young as the clouds, and somebody said, as the mist.”

Baidy Rico Mendoza fashions her clay people out of disparate things—it may be from a passage from the Scriptures, a word, an interesting face, a place she’s seen, or even a remembered snippet of conversation. With quick, deft fingers, she patiently molds each piece into shape, even as she adjusts to its plastic possibilities, smoothing and investing each inch of the clay with thought and care. All these years of working with the medium has taught her that a tiny air bubble carelessly left in the clay is enough to cause damage to the piece once it is fired in the kiln. All this experience, too, of working with the materials and tools, as well as the temporal demands of her art, has given her a philosophical view of life, and imbued her with an ageless wisdom borne out of being constantly in touch with her instinctive nature. Baidy Mendoza is spiritual even as her philosophies on life and art are also deeply rooted in nature—literally embedded in the red soil where she derives her creativity.

Had she lived in pre-colonial times, Baidy Mendoza would most certainly have formed a kinship with the babaylans,

…who molded the spiritual and ritualistic lives of the people in that time period. These women provided healing, wisdom, and direction with life and moral stories, myths, poems, prayers, and hymns.

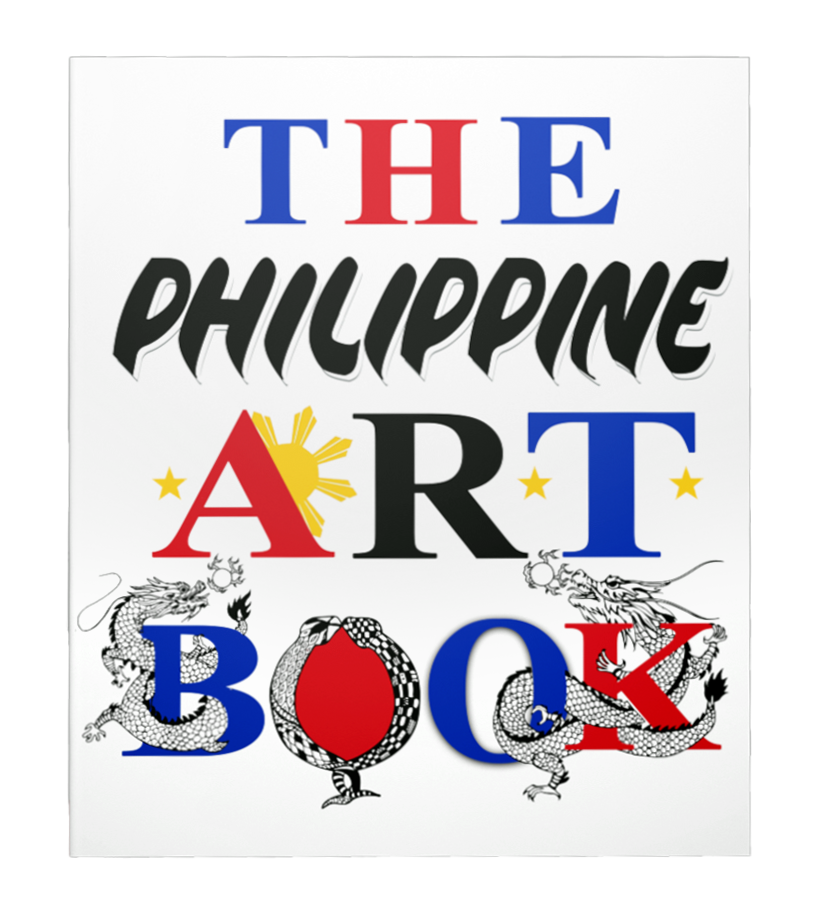

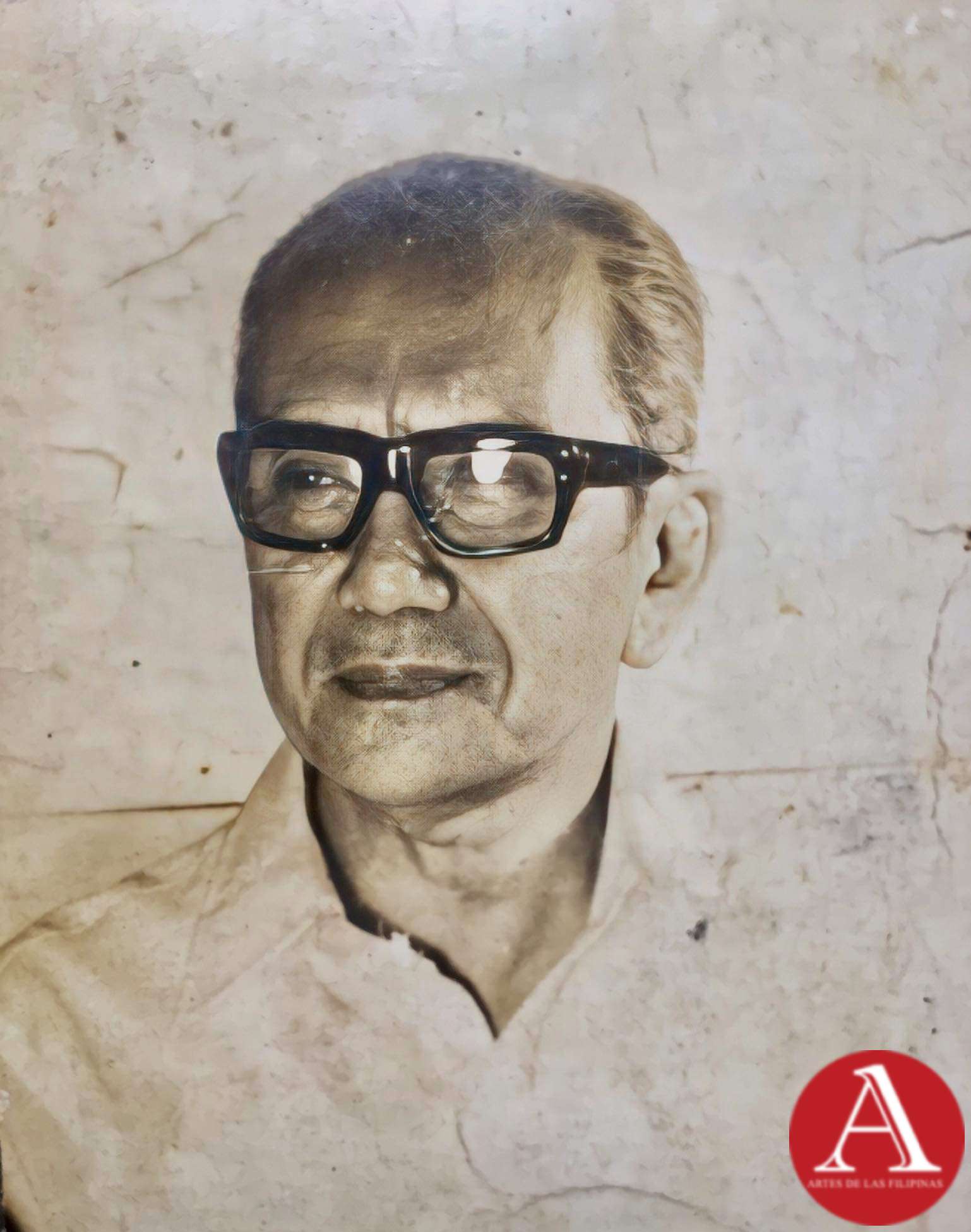

Fig. 1. Photo of Baidy Mendoza at eighteen.

Born to an artistic family, Baidy Mendoza discovered her calling to art early enough. The very creative home environment sustained the young girl’s fascination for dolls. Although the Mendoza family was well-to-do—after all, they partly owned a school in Lingayen--the young Baidy Mendoza, then only in high school at St. Joseph’s College in Quezon City and still practically a child, accepted commissions to make and fix dolls. The enterprising young girl even consigned her creations at the then fashionable Berg’s department store in Escolta. Among the clients of her early artistic career was Mrs. Mary Ejercito, the mother of Erap Estrada, who made cakes which she decorated with dolls she copied from photos the older woman gave her.

After receiving her Bachelor of Philosophy degree cum laude from the University of Sto. Tomas, Baidy took off for the States. In Loveland, Ohio, she went to Grailville and studied sculpting under Trina Paulus, paper art under Jeanne Hieberg, and apprenticed under Bill Schickle. Grailville--a center for arts, spirituality, global solidarity and environmental causes--was established by members of The Grail, an international lay Catholic women’s movement. (The Grail in the U.S.A.)

Baidy Mendoza found herself in the right place, at the right time. This was in the sixties—an exciting decade, particularly in America, for the arts and literature, the rise of the feminist movement, as well as the emergence of ecological awareness.

From there, she went on to the Netherlands in Detiltenberg, Vogelenzang for further studies. There, she finally joined The Grail. The changes in the Church in the late 60s and 70s and the growth of the women’s movement necessitated for it to be inclusive of other religious traditions, making of its members pioneers in Catholic feminist theology.

With some friends from The Grail, Baidy took a trip to Egypt, and made excursions to see the museums, monumental pyramids and sculptures, and got exposed to the art of antiquity—so unlike anything she’d seen before. Coming back to the Netherlands, she was asked if she would be interested to work in Indonesia. At that time, the last Dutch were leaving Indonesia, and they needed somebody to fill in the post of a Jajasan Adat Istiadat Barat, adviser on Western culture in Surabaya, East Java, in a Sekolah Repandian Puteri—a teacher training college for women. Baidy Mendoza was only too happy to accept; she was convinced that she would blend in easily because of her skin, but more than that, she was extremely fond of the golek puppets (wooden puppets), and saw also in the job offer an opportunity to touch base with her creative roots. Her actual job description, though, had very little to do with art: she was supposed to instruct diplomats’ wives on practical matters like fashion and etiquette, give them orientation on living in a different culture, and thus, properly prepare them for living abroad.

Living in Indonesia for three years, Baidy Mendoza eagerly soaked up the art and culture the country had to offer. Her experience of the place--particularly in the artist village of Ubud, in Bali--formed a critical part of her early artistic insights. The powerful attraction Indonesian culture held for her was its proximity to her own—the first settlers in the Philippines, after all, had come from Indonesia and China on foot via land bridges which had long since vanished—and she was keenly interested to see where the break happened, with regard her “forefathers”.

Between her duties at the college, she still managed to study batik art under Ibu Moied, and Muslim art and culture”The Wayang” under Pak Karnadi, and the gamelan “Saron” under Pak Soenardjo.

The babaylan “acquires her powers through her initiation. During the days, weeks, months or years of her initiation, she disappears from home.” (Demetrio 131) Ironically, Baidy Mendoza had to leave home to find herself. Just like her pre-colonial counterpart, it was a requisite to the role she is later to play in her life. Perhaps the process was necessary so that she may be shed of the superfluous layers and she may then be able to find the essential core of her existence in a foreign land. It took years before she would trace the path back to home, but when she did, she made sure she was ready.

She came back home to Manila in 1968, her head teeming with ideas she wanted to try out, having gone to different places and having witnessed so many different things. But first, she had to decide what she was going to use as her medium. She made the rounds of the galleries at that time, and noticed that they were empty of anything glass, enamel or clay. And so she finally settled on clay and immediately set to work.

The first presentation of her works to the public was entitled “Dalin Ya Peteg”—literally, Pangasinan term for true earth—after the red clay she gets from the mountains and riverbeds of her parents’ hometown of Labrador. She had 100 pieces in that show and she held it in her Cubao studio.

The years Baidy Mendoza spent travelling and living abroad resulted in a body of work with the distinct qualities she eventually came to be known for: a whimsicality and a folksy, aged and natural feel. Her pottery and sculptural pieces look like they’ve been around forever, that once they were actually mistaken for anthropological artifacts in a gallery abroad. Collectors began taking interest in her work, and they began snapping up her pieces and commissioning her for special projects. Even up to now, hardly has the pieces dried and been fired in the kiln, and they are all--already--incredibly sold out.

On top of this, people lined up for her pottery workshops as well. Thus, Baidy Mendoza successfully achieved what she originally set out to accomplish—the promotion of her clay creations among the public.

(To be continued...)

Recent Articles

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISM

FEDERICO SIEVERT'S PORTRAITS OF HUMANISMJUNE 2024 – Federico Sievert was known for his art steeped in social commentary. This concern runs through a body of work that depicts with dignity the burdens of society to...

.png) FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO

FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISOMarch 2024 - Alexander Narciso is a Philosophy graduate from the Ateneo de Manila University, a master’s degree holder in Industry Economics from the Center for Research and...

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim HigginsSeptember 2022 – The fashion exhibition of Salvacion Lim Higgins hogged the headline once again when a part of her body of work was presented to the general public. The display...

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All TimeOne of the emblematic komiks writers in the Philippines, Jose Zabala Santos contributed to the success of the Golden Age of Philippine Komiks alongside his friends...

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

The Philippine Art Book (First of Two Volumes) - Book Release April 2022 -- Artes de las Filipinas welcomed the year 2022 with its latest publication, The Philippine Art Book, a two-volume sourcebook of Filipino artists. The...

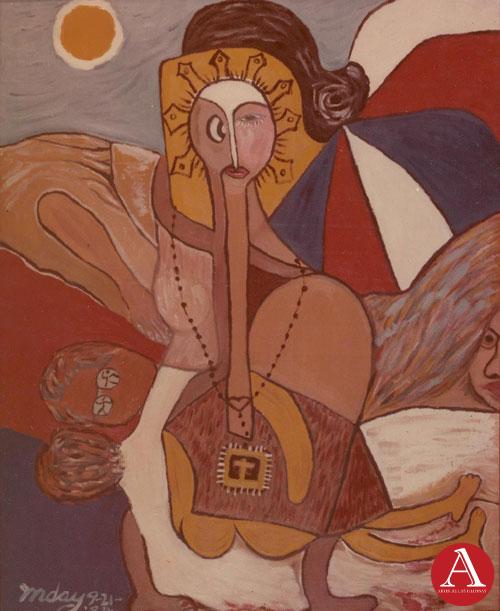

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and FoundJune 2018-- A flurry of renewed interest was directed towards the works of Lamberto Hechanova who was reputed as an incubator of modernist painting and sculpture in the 1960s. His...

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise CemeteryApril-May 2018--The Pere Lachaise Cemetery in the 20th arrondissement in Paris, France was opened on May 21, 1804 and was named after Père François de la Chaise (1624...

Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday

Inday Cadapan: The Modern IndayOctober-November-December 2017--In 1979, Inday Cadapan was forty years old when she set out to find a visual structure that would allow her to voice out her opinion against poverty...

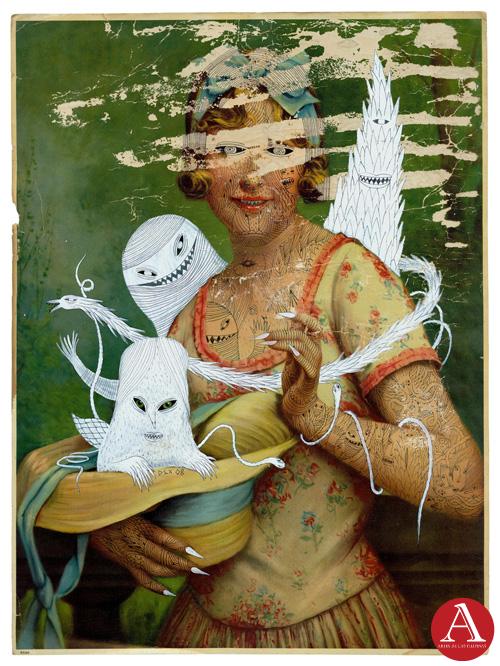

Dex Fernandez As He Likes It

Dex Fernandez As He Likes ItAugust-September 2017 -- Dex Fernandez began his art career in 2007, painting a repertoire of phantasmagoric images inhabited by angry mountains, robots with a diminutive sidekick,...