BOOK REVIEW: EDIFICE COMPLEX: POWER, MYTH, AND THE MARCOS STATE ARCHITECTURE

Reviewed by: Architect Roselle Santos

The book is about Marcosian Architecture. The author started each chapter with quotes from different scholars as an introduction to his discussions. The book is very much influenced by Michel Foucault’s discourse on power and knowledge.

Lico says that Marcos regime recognized the nexus of architecture and society, its potential for influencing the community, and wielded this weapon to promote the aesthetics of power in the built form.

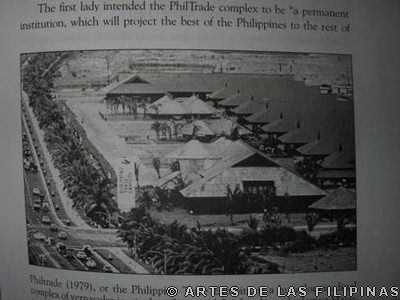

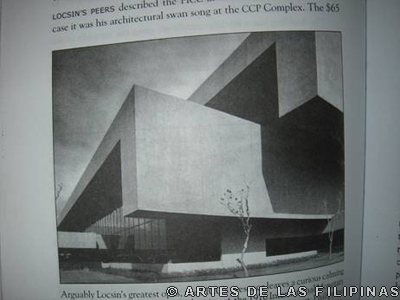

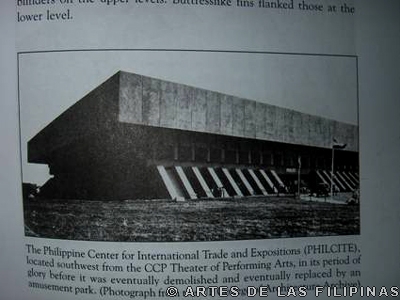

The book seeks to contribute to theoretical work on the relationship between architecture and power. It documents some of the socio-historical dimensions of the Marcos regime’s major architectural accomplishments which include the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Folk Arts Theater, PHILCITE, Philippine International Convention Center, Philippine Trade Pavillons, Tahanang Pilipino (Coconut Palace), and the Manila Film Center. Through this book, Lico hopes to generate awareness of the unrecognized power of architecture.

The book investigates how state architecture functioned as one of the authoritarian regime’s legitimizing mechanism for socio-political control. He hopes to introduce a novel way of writing Philippine architectural history, which has been plagued by formal rules and stylistic canons (include issues of power relations). He, however, asserts that there is no absolute view, concentrated on the socio-historical narrative of buildings situated at the reclaimed foreshore development in Manila Bay.

Chapter 1 (Architecture and Society) starts with a quote from Norris Kelly Smith about architecture revealing that “not only the aesthetic and formal preferences of an architect/client but also the aspirations, power struggles and material culture of a society.” The author said that architecture implicates “space” and its utilization as “place” by its occupants. He called on Michel Focault’s “hybrid concept of power-knowledge” to explain how space is created and arranged “to gain control over knowledge” through “surveillance and asymmetrical visibility”( the gaze). Foucault introduces the term “panopticon” or knowledge tied to systems wit human beings as objects of disciplinary knowledge.

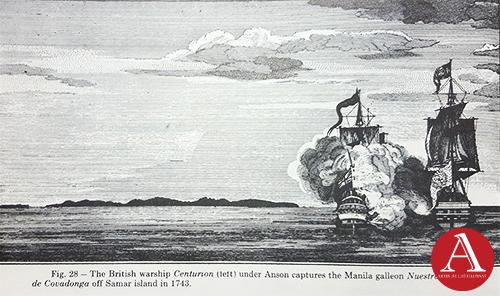

Chapter 2 (Cartographies of Power in Philippine Architecture) reconnects with how power was exercised through architecture in the Spanish and American colonial periods, during Japanese occupation and in the succeeding periods. Chapter 2 explains the historical role architecture played in wielding power over colonized people set the stage for more detailed narrative Marcos state architecture as a conduit of power.

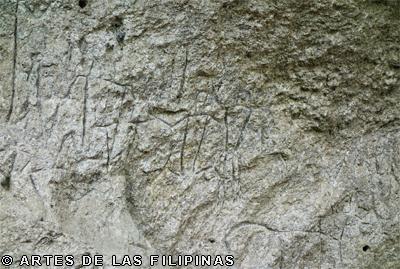

He discussed the Spanish colonization where church is the center in the development. Town plan should establish a main plaza, principal street traverses on one side and secondary streets in gridiron pattern, which the church as the center and a bell tower that served as a panoptical device. Native population was resetlled “under the bells” and that Catholicism was used to control the people. He presented Juan Palazon’s book on Majayjay that smash the singular notion that colonial subjects gained spiritual satisfaction from church building.

After the Spanish empire signaled the emergence of monumental neoclassicism in the Philippines — the advent of American colonialism and its cultural dominance. The Americans appropriated 1million dollars for the construction of roads and bridges. In 1901, Taft appointed Arcadio Arellano as consulting architect and Neo-classical style was at the forefront of Maerican Colonial Urbanism. Neo-classicism was ordained as the official architectural style. To materialize the myth of an American Tropical Empire, Daniel Burnham was sent to survey Manila and Baguio and make preliminary plans to develop the two cities (Burnham- advocate of “City Beautiful Movement”). Burhnam designed the plans but most of the buildings were designed and built by William Parsons (consulting architect from 1905-1914). Parsons used “hybrid colonial style”- he adjusted the style for hot-humid tropical climate. He also built schools, hospital, hotels and clubs. Each building or development has its equivalent in the US.

Some Filipino architects designed other buildings, aimed to re-create the image of Washington D.C, in the Far East

– Juan Arrellano – Post Office ( 1931)

– Antonio Toledo – Agriculture and Finance Buildings ( 1936)

• 1920’s and 1930’s – development of Escolta ( Wall Street)

• 1930’s- cinema ( Hollywood)

• 1935 – Phil. commonwealth ( Filipinos ready for self-governance)

President Quezon contacted Parsons to build a “New Capital City,” but unfortunately he died and was replaced by Harry Frost who developed the comprehensive plan in 1941. However, the Pacific war interrupted President Quezon’s dream, World War II and the Japanese occupation and the 1945 battle for liberation destroyed Manila. According to the author, during the war and the transition from American rule to self-governance, the Philippines had no discernable architectural product to speak of.

Chapter 3 (Culture and Architecture under Martial Law) uncovers the methods by which authoritarian state power and architecture coalesced to rejuvenate an alleged national cultural identity and to sustain the myth of a democratic revolution. The author discussed the twenty years of “conjugal dictatorship” reign of Marcoses from the first time Ferdinand Marcos was elected as president then became the first Philippine president to win a re-election to the time he declared Martial Law (claiming it was the country’s last defense against disorder). Marcos created the new social order “Bagong Lipunan.” Imelda Marcos became Governor of Manila and Minister for Human Settlement.

President Marcos nurtured a myth for what historians termed as ‘ palingenesis”, a form of utopianism which evokes the idea of rebirth or spiritual regeneration. They attempted to create a singular national identity under the catchphrase “isang bansa, isang diwa.” Presidential Decree’s and Proclamations, Executive Orders and alterations in the constitution and other state-ordained policies facilitated the concretization of all these imaginings. They presented themselves as parental figures and they have various self-glorifying projects in the form of sculptural landmarks and allegorical paintings ( stone bust, Si Malakas at si Maganda, murals as Inang Bayan, Sto. Nino shrine in Leyte, San Juanico Bridge, the book Tadhana). Imelda Marcos even traced her genealogy all the way back to ancient Rome, claiming that “Romualdez” means “Alcaldez de Roma” which literally translates to “rulers of Rome.”

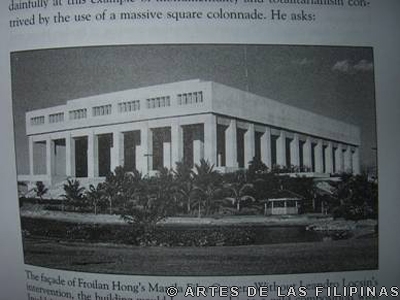

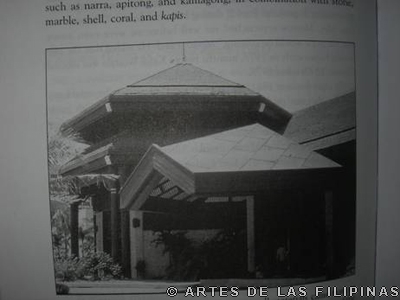

The author describes the Cultural Center of the Philippines complex as a symptom of Imelda’s “edifice complex.” The “edifice complex” is a syndrome which plagues an individual, nation, or corporate institution with an obsession and compulsion to build edifices as a hallmark of greatness, as a signifier of national prosperity, as a conveyor of an individual’s status or as a projection of a corporate image. The project was propelled by their desire to impress– the conjugal dictatorship invested over 19 billions pesos between 1972 and 1977 alone. Several churches, public buildings and parks were restored and a lot of projects from slum upgrading to monumental edifices using the new architectural formula called “folk architecture.”

Chapter 4 deals with the The Cultural Center of the Philippines complex.

Chapter 5 (Power and Myth in Marcos StateArchitecture) analyzes the mythologies that govern the architectures of the CCP buildings. It detail the urban myths of Monumentalism (postulated that Imelda’s edifice complex was intended to compensate for the lack of something else. Since the Philippines has no great tradition in architecture that bears witness to colonial past- why not invent and create them.); the myth of modern Progress (the illusion of modern progress as demonstrated by monumental building spree of the Marcoses); the myth of modernity (Modernity in cultural and architectural production was intended to bolster the regime’s dubious claim to progress and national identity. Buildings put up by Imelda were not modern at all.); the myth of nationality and collectivity (Marcosian dream of a pure, homogeneous and timeless essence of the Filipino as mere imaginations and projections of a supposedly consolidated nation. While the buildings and complexes are supposedly public domains, many people have kept their distance from these domains because of alienating character of the building.)

Chapter 6: (Beyond Frivolity and Political Amnesia) The author said that architecture is not a neutral homogenous space- it does not simply embody but rather is invested with values and ideologies in often insidious ways. He points out that it is important to understand architecture beyond its materiality and expose the underlying narratives and myths and the complex socio-economical-political forces that impinge on and likewise bear the brunt on their existence. The author says “in doing so, we hope that oppressive architectures can be reclaimed and rearticulated into structures of emancipation and agents of the people’s empowerment.”

Overall, the author made use of extensive researches, documentations and critical assessments of previously written documents, or archival photographs and illustrations and of pertinent buildings/architecture and built spaces. He properly cited all sources and his socio-historical approach made the reader appreciate more the architecture cited. The book is relatively easy to process. Highly recommended!