PAETE’S TAKA

by: Mailah Baldemor

Beautiful flowers of scarlet red adorn her from head to toe. Big, round, expressive dark eyes govern her proud head and a red stiff tail enhances her powerful back. A small horse; my first taka toy I received from my father. A work of art and a loving gift from a Paetenian.

Paete, Laguna is one of the Philippines’ last remaining artistic strongholds and may be accessed either by passing through the picturesque zigzag of the Eastern Rizal route or through the long stretch of the South Luzon Expressway. The town is known for two things: fine woodcarvers and the golden sweet fruit of lanzones.

Paete derived its name from paet, a Tagalog word for chisel, a principal tool used in woodcarving. The proper pronunciation of the town’s name is probably “Pa-e-te”, but natives call it “Pay-ti” (Pi-tè) with the guttural “e” sound at the end. Only when conversing with visitors and outsiders do Paetenians use “Pay-ti.” When the American Maryknoll missionaries came to Paete in the late 1950s, they even referred to the town as “Piety.”

Upon entering the town, you will be welcomed by workers laying brown paper or newsprint papier-mâché pieces (taka) on the roadside for drying. To complement this picture, your nose will probably wiggle delightfully to the smell of gawgaw (starch) paste, wooden logs, and burning sawdust.

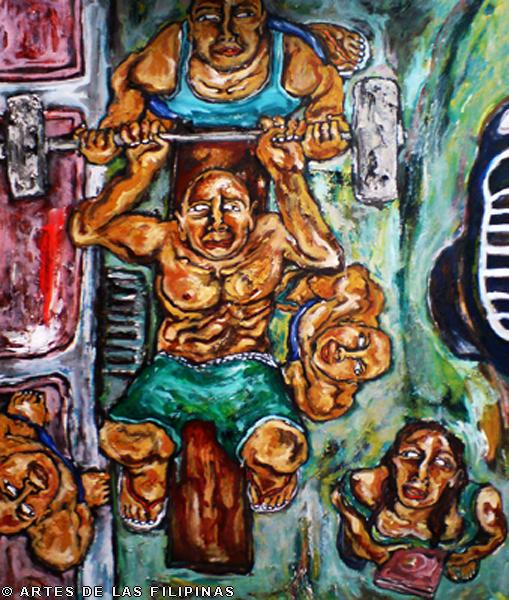

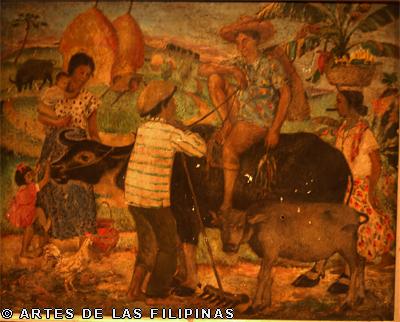

The takas from the road shops are “carved during any season to identify any particular season”. You could chance upon the workers making Christmas key figures of Santa Claus, Rudolph the Reindeer, and Frosty the Snowman during the sunny days of April in preparation for the Christmas season. These designs, however, are seasonal and are requested by clients. Inside the town, almost all shops sell different Filipino-inspired designs of carabao figurines, Maria Clara dolls, and horses in a variety of choices. Some new designs have also been incorporated which now includes the querubins, toy soliders, giraffes, rabbits, and a variety of fruits– all in different colors and sizes.

Takas have indeed become the epitome of folk art. They exist in every possible bright and happy color combination, simplified curvilinear forms, flora & fauna motifs, sweet innocence, and delectable charm. These designs change rapidly as time goes by. The development of the taka and takaan (and any cultural norm for that matter) usually spread in an outward path from its source. The present generation seems to have forgotten where the taka originated. The Paeteños believe that the idea originated in Mexico with a significant difference to what we have in Paete. While the Mexican “pinata” is decorated with cut-off colored paper, the Paete’s takas are hand-painted and are sometimes small enough for little girls to use as dolls.

According to Quesada:

In Paete we likewise had woodcarvings of figures of animals, carts and men or women. The carvings were molded in paper and paste, dried out in the sun, then the molds were surgically taken out of its cast. The product was then put together again, dried another time and painted brightly to be sold as toys.

According to the Paete Phenomenon exhibited in the Bulwagang Juan Luna at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Maria Bague made the first known taka in 1920s. It was wrapped around a mold carved from wood and painted with decorative pattern that eventually became toys and ornaments. Unfortunately, nobody knows if Maria Bague’s taka ever existed as her town was destroyed by fire and almost all traces of the takas she produced have vanished.

The art of taka-making further developed during the American period when the rising newspaper industry produced more newsprint. However, the introduction of plastic toys during this time took its toll on the taka industry, causing it to slowly lessen its demand and, consequently, its production. The taka industry did not rise to its peak again until the mid-70s and early 80s.

Paete has a rich history in the visual arts. Logs of acacia, molave, tipolo or batikuling being loaded onto sawmill or carving shops are a common sight here. Unfortunately, the forests of the Philippines are rapidly being destroyed and plant species are slowly disappearing. The townspeople must learn how to replace the trees felled by the woodcarving industry as the only hope of preventing the ecological, social, and human tragedy was imperiled by this industry.

Since wood is the principal source of woodcarving, the government under President Corazon Aquino implemented a Total Commercial Log Ban Bill in 1992. The total log ban was a good first step in restoring our depleted forests. In another instance, one particular group initiated the “Save the Sierra Madre Movement” to protect the remaining patch of virgin forest in Luzon. This anti-logging task force, responsible for confiscating millions of pesos worth of logs and logging equipment, is also one in helping the government protect our forests.

In the midst of all campaigns to preserve our forests and with the implementation of the Senate Bill for Total Commercial Log Ban, papier-mâché may just be the perfect substitute for wood. As a result, papier-mâché has become the folk art of the Paeteños. Taka makers begin this process by hand carving hardwood sculptures which later on becomes the positive wooden molds (takaans). The takaans are then coated with wax release agents or gewgaw (starch) then hand-painted in a variety of bright and happy colors for embellishments.

Today’s taka-makers have developed and improved their products. From their indigenous to modern designs, the materials they now use are carefully crafted and has incorporated finishes of stucco, gold, finely painted enamel or lacquer and are sold for export. Some takas are also being use for backdrops for television and mall displays. Truly, the taka has gone a long way from its humble beginning.

After so many years, I didn’t realize how important the taka was. A little toy my father gave me many years ago plays an interesting part in the history of arts. I seldom see that red colored taka horse anymore. But I thank my father for that little toy he gave me.

A little piece that made a history.